What I told the 2025 graduates of Concordia University Nebraska:

When I was in college, long, long ago, during the first week of classes, I picked up a piece of paper from the ground. I don’t know why I did that. I don’t normally pick up other people’s litter. But the paper looked kind of official.

It was a drop/add slip. I didn’t exactly know what that was at the time, but there was a name with a telephone number, so, just in case it was important, I thought I’d give the person a call.

We arranged to meet so that I could give it to her. It turned out, she had gone to this French class but she couldn’t stand the professor, so she decided to drop the course.

To make a very long story very short, two years later, we got married. We would have three children and eventually twelve grandchildren.

If I hadn’t picked up that piece of paper from the ground, my life would be completely different and almost certainly not nearly so happy. If I just stepped on the paper and walked on by, my three children would never have been born. If I were a good citizen and picked up the paper but threw it into the nearby trash bin, my twelve grandchildren would not exist.

If my future wife’s professor had had an extra cup of coffee that morning, maybe he wouldn’t have been so boring. She would have stayed in the class, not filled out a drop slip, and we would never have met. And if she had been just slightly more careful about her personal belongings, she would have kept her drop/add slip in her backpack instead of losing it and would probably have found someone better to marry, while I would have become a lonely, bitter old man.

Our lives are filled with small, seemingly insignificant moments. But they can turn out to be very significant, though we cannot know that significance at the time. Only when we look back can we see the complicated pattern that brought us to this present moment.

Such seemingly random moments with huge consequences multiply as we go deeper into the past. Big events also can have very personal consequences. If the Japanese had not bombed Pearl Harbor, my father would not have left the farm to join the army, which later enabled him to go to college on the GI Bill. On his way to class, he decided for some reason to walk on the other side of the street. My future mother was walking in the other direction. They approached each other and started talking. If that hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t be here giving a commencement address. I would not exist. My wife’s father joined the Marines and fought at Iwo Jima. In his unit, only five men survived, and he was one of them. If he had been killed, my wife would never have been born, nor would our three children, nor would our twelve grandchildren.

I urge all of you to play this game, to think about all of the coincidences, random events, casual decisions, and happenings that could have gone in a completely different direction and how they all worked together to bring you where you are today. A pattern will emerge. It will look like your life was orchestrated by some higher power. This is because it was.

Concordia’s theme for this academic year is 1 Corinthians 15:10: “But by the grace of God I am what I am, and his grace toward me was not in vain. On the contrary, I worked harder than any of them, though it was not I, but the grace of God that is with me.”

You are what you are by the grace of God. This does not mean you haven’t worked hard to get to this point in your life, graduating from college and getting ready to launch out into the world. But God is with you. Specifically, the grace of God—his unmerited favor that is ours through Christ—is with you every step of your way.

This promise is repeated again and again in Scripture. “The heart of man plans his way,” says Proverbs 16: 9, “but the Lord establishes his steps.” We do and should plan our way—making countless decisions, setting our goals, doing what we can to achieve them—and yet, at the same time, the Lord is establishing our steps: guiding us even when we aren’t aware of it, making things happen, protecting us, leading us where He wants us to serve.

Perhaps the most well-known Scriptural passage on this theme is Romans 8:28: “We know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose.” Now this is not teaching blind optimism. All things do not work together for good for everyone. This promise is “for those who love God” and “are called according to his purpose.” That is to say, this passage is about Christian vocation. (Some of you have been waiting for me to bring up that concept.)

According to Luther’s doctrine of vocation, God will call you to tasks and relationships in the family, the workplace, the society, and the church. Sometimes you may not see how all things are working together for good in all of your vocations, but the emphasis in this text from Romans is on God’s purpose, not necessarily your own. The purpose that God gives you in all of the vocations to which He will call you is to love and serve your neighbors: your spouse if He calls you to marriage; your children if He calls you to parenthood; your customers when He calls you to a job; your fellow citizens when He calls you to communities and your country; your fellow Christians when He calls you to the church. And when your purpose is aligned with God’s purpose, His love and service to His creation is carried out through your love and service to His creation.

Right now, at this pivotal moment of your life when you graduate from college, you may be wondering what is ahead, even worrying about what is ahead: Will I find the right person to marry? Will I have children of my own? Where will I live? Will I get a good job? Some of you have already travelled a ways down this path, but you are all probably wondering right now, how will my life unfold?

Just remember Psalm 31:15: “My times are in your hand.”

When David was made king of Israel, he prayed, “Who am I, O Lord God, and what is my house, that you have brought me thus far?” (1 Chronicles 17:16). God has brought you thus far, through your childhood, your adolescence, your adulthood, and now your college education. Look back, and you can clearly see His hand through it all.

The present may be confusing, and the future is uncertain. But realize that God is with you now and will continue to be with you in the future, just as He has been with you in the past—bringing people into your life, leading you where He wants you to be, always blessing you abundantly with His grace.

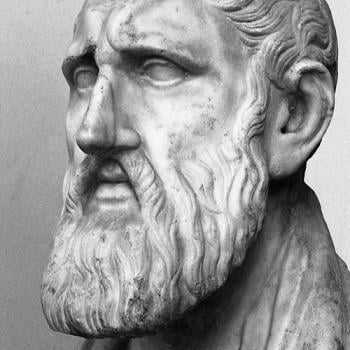

Photo by StefanSalavatore, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons