Democrats have been floundering since losing the 2024 election. They have lost all three branches of the government. The public seems to have repudiated their woke progressivism. The base they were counting on in their strategy of identity politics–blacks, hispanics, and the working class–has turned against them.

What should they do now? Some Democrats are saying the problem is that they weren’t radical enough while others say they were too radical. Some are putting their hope in a revival of “resistance” to Donald Trump, thinking that if they demonize him enough, surely Americans will come to reject him. Others think that co-operating with the Republicans, at least to a degree, will improve their image.

The overall problem seems to be that Democrats lack a coherent ideology, one that can give their party direction and inspiration, and, more than that, make themselves popular with voters.

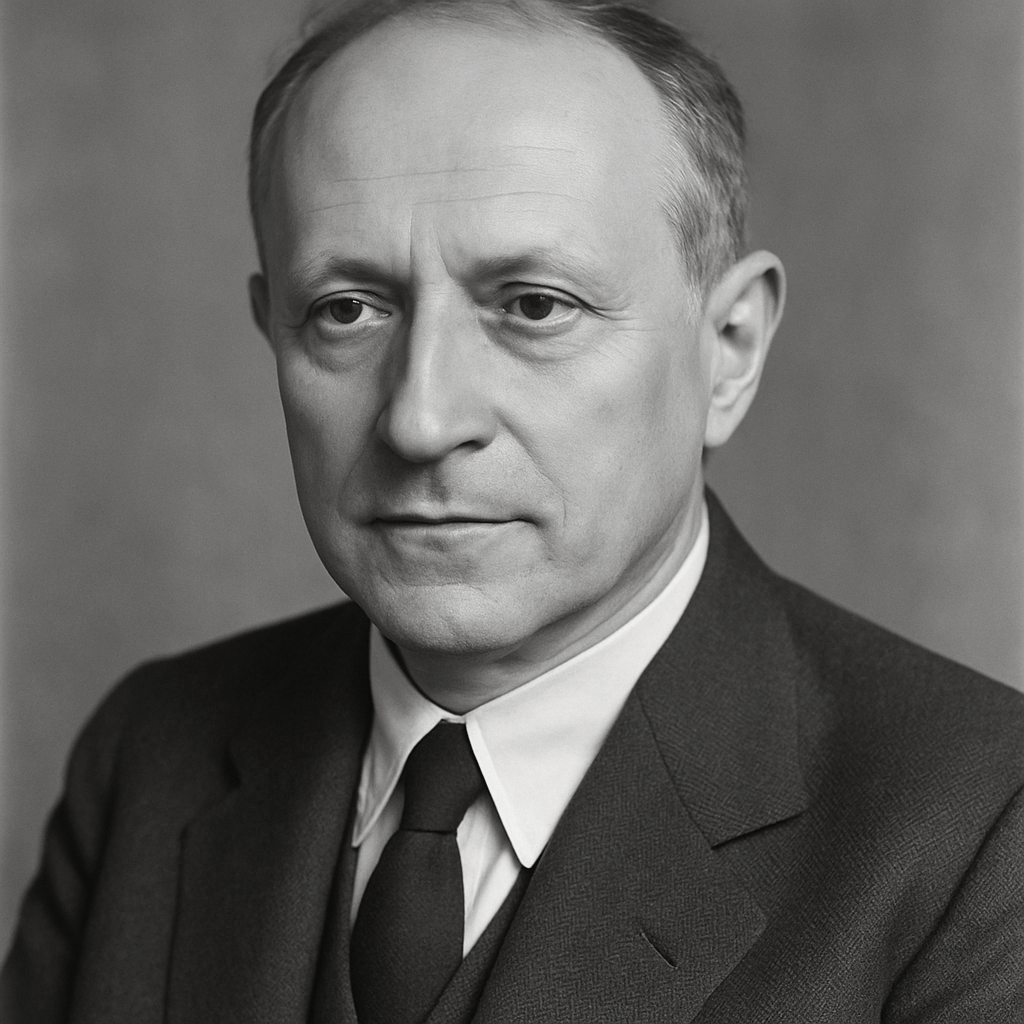

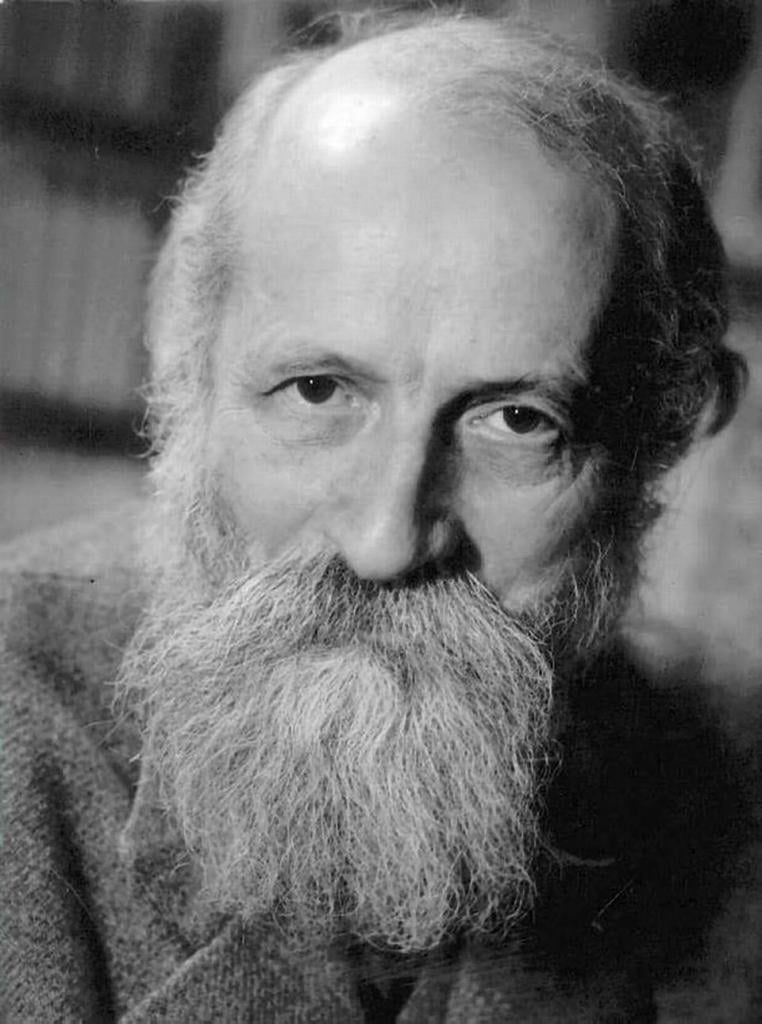

Two journalists, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, are proposing such an ideology, a new kind of liberalism. They have written a book entitled Abundance. It is a manifesto for what is being called “Abundance Liberalism” or “Supply-Side Progressivism.”

Here is how Klein describes it in a piece for the New York Times entitled There Is a Liberal Answer to the Trump-Musk Wrecking Ball. (also available from out behind a paywall here):

The populist right is powered by scarcity. When there is not enough to go around, we look with suspicion on anyone who might take what we have. That suspicion is the fuel of Trump’s politics. Scarcity — or at least the perception of it — is the precondition to his success.

The answer to a politics of scarcity is a politics of abundance, a politics that asks what it is that people really need and then organizes government to make sure there is enough of it. That doesn’t lend itself to the childishly simple divides that have so deformed our politics. Sometimes government has to get out of the way, as in housing. Sometimes it has to take a central role, creating markets or organizing resources for risky technologies that do not yet exist.

Abundance reorients politics around a fresh provocation: Can we solve our problems with supply? Valuable questions bloom from this deceptively simple prompt. If there are not enough homes, can we make more? If not, why not? If there is not enough clean energy, can we make more? If not, why not? If the government is repeatedly failing to complete major projects on time and on budget, then what is going wrong, and how do we fix it? If we need new technologies to solve our important problems, how do we pull these inventions from the future and distribute them in the present?

Klein admits that government and, indeed, liberal Democrats have been actively blocking such abundance. He wants that to stop. The regulations that stifle big projects and the attitudes that stifle growth are addressing the problems of a previous generation, but the problems have changed.

Unherd‘s Sohale Mortazavi sums up Abundance Liberalism this way: “In their buzzy new book, Abundance, they argue that scarcity is a choice, and that ‘to have the future we want, we need to build and invent more of what we need.’ Progressives, in this telling, must be on the side of dynamism and productive capacity, even if this means bucking the Left’s orthodoxies.”

In a wide-ranging interview with Klein and Thompson in The Free Press, Thompson says, “I think we went from a world where liberalism was a liberalism of building, between the 1930s and 1960s, and then there was a turn in the 1960s and 1970s, and for the last half century, liberalism has too often meant a liberalism of blocking.”

Abundance Liberalism gets away from, for example, the ascetic strictures of the environmental movement, while still seeking to build technologies that will fight climate change. It tones down progressives’ traditional class-warfare rhetoric going back to Karl Marx that demonizes business.

It is still progressive, though, in the sense of bringing back the old faith in “progress,” the trust in science, technology, expertise, and social evolution that can bring on a bright, utopian future. This would seem to fit well into the current Democratic base, no longer the working class, but the affluent, well-educated “knowledge class.”

But, you might wonder, how are these policies and ideology different from what the Republicans are trying to do? What’s the difference between Klein’s technological utopia and Donald Trump’s “golden age”?

The Trump administration is also calling for abundance. Techno-optimists like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and Marc Andreesen have been saying something similar–as Klein and Thompson in their interview admit–but they have aligned themselves with Trump. Though conflict with MAGA populists has arisen, J. D. Vance, with a foot in both worlds, is trying to reconcile the two.

Here is the difference and what puts the “liberalism” in Abundance Liberalism. Klein and Thompson believe that a strong and active government is the key to achieving abundance. Whereas what we might call Abundance Conservatives believe that the key is unleashing the private sector.

Klein tells the Free Press, “One of the things we’re quite focused on is deregulating the government itself so government has more capacity to act, and act with a certain strength and capability. High-speed rail, or for that matter, public housing, are both good examples of this. There are places where you would want government to be able to act with more agency, more autonomy, and not be quite so vulnerable to endless lawsuits.”

Klein and Thompson have a big problem with Musk precisely because he is tearing government down. They want to build it up and make it both stronger and more effective.

Trump and the Republicans, they say, are really all about scarcity. For example, they discuss the high cost of housing, due to a housing shortage. So we need to build more houses. They admit that the problem is worse in Democratic-run states, like California, due to all of the regulations, restrictions, environmental studies, union rules, etc., etc.

They see a better alternative in Texas, where it is much easier to build houses due to fewer regulations and where housing is much cheaper. Thompson, speaking of Trump, says to Free Press,

He could have said, let’s make America like Texas. Let’s make America the most housing abundant country in the world. Instead, what does he do? He raises tariffs on Canada and Mexico. Totally effing random, but let’s follow along. Our number one source of lumber to build houses comes from Canada. Our number one source of gypsum drywall comes from Mexico.

Two of the most important inputs for any new house you’re going to build, we’ve now slapped a 25 percent tariff on them. There’s no way that does anything other than drive housing prices right up. And by the way, he’s also decreasing immigration. Twenty-five percent of the construction labor force is foreign-born. In California, it’s closer to 40 percent.

OK, some fair points, but they have to do with Trump’s stepping away from the usual Republican position of free markets. He argues, of course, that decreasing immigration will mean more jobs for Americans and that tariffs on foreign imports will encourage American companies to supply lumber and manufacture drywall. We’ll see who is right.

But let’s follow this along. Say the Abundance Liberals get control and government–somehow gaining a competence it hasn’t usually shown–builds more houses, a “supply-side” solution. That will drive housing prices down. Will affluent “knowledge class” progressives appreciate the value of their homes going down? Will the Abundance Liberals abandon the unions, as Texas has? Will they make houses that people really want to live in, if they are supplying apart from consumer demand?

The biggest problem with Abundance Liberalism is that it means an even more powerful, all-pervasive government, one big enough to give us an abundance of everything. And, as a practical matter, government spending on a colossal scale at a time when it is already laboring under a $36.22 trillion debt.

Thompson admits to Free Press, “I’m a tax-and-spend liberal. I believe in high taxes on the wealthy because I believe in income distribution, because poverty, I believe, is a moral sin.”

Well, if you distribute income like that, you won’t have anyone wealthy enough to pay high taxes! Of course, if you eliminate the private sector as a source of investment, the government will have to do it all.

That is socialism, a rather old-fashioned progressive idea, but this is what Abundance Liberalism comes to. To see the kind of building socialist governments manage, freed from market forces, go to Russia or other places ruled by the Soviet Union and see what’s left of the ghastly, impersonal high rise apartments now crumbling from neglect, or talk to someone who lived under that kind of regime about the kinds of products available in their shops.

If Abundance Liberals rely on the tactic of “tax and spend,” they are not that different from regular liberals.

Illustration via Amazon.com