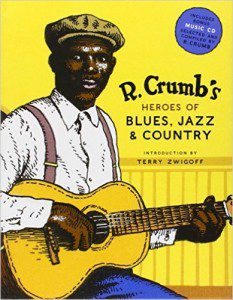

I just ordered R. Crumb’s Heroes of Blues, Jazz, and Country . The reason I did is I wanted to see the reverent Crumb in order to contrast him in my own mind with the irreverent Crumb.

Crumb is often accused of irreverence. And he often guilty as charged; but I suspect there’s more to his irreverence than meets the eye.

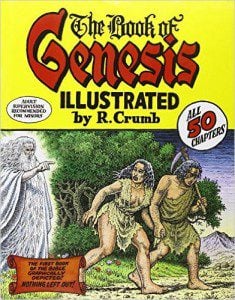

His treatment of Genesis is mixed, in parts a reverent handling, in others not–actually blasphemous, technically speaking. I’ll get to that, but I want to explain what I mean by reverence first, because little of what I will say will make sense unless I do.

I like Paul Woodruff’s thinking on reverence in his book, Reverence: Renewing a Forgotten Virtue.

Betty Sue Flowers, the Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin, sums up Woodruff’s thesis. She says in the forward to the second edition:

…the opposite of reverence is not irreverence but hubris–forgetting, in the pride of power or glory, that you, too, are human, with human limitations, and must respect the humanity of others. Reverence, says Woodruff, is the source of the capacity for respect. But it lies deeper than respect, because it is not simply behavior; it is aligned with truth. Reverence is the “capacity to have feelings of awe, respect, and shame when these are the right feelings to have.

Reverence then is a mixture of humility and awe. It’s owning up to your smallness and at the same moment recognizing the greatness, and the “otherness” of something, or someone else. Christians and other religious theists know that this starts with reverence for God. But it shouldn’t surprise us that unbelievers are still capable of reverence. Unbelievers can still revere things, or people, or great truths. I’ve known atheists, for instance, who almost speak in hushed tones when discussing a scientific discovery. Is this wrong or idolatrous? No, not necessarily. The universe is tiered. If the inference is followed correctly, any thing, or person, worthy of reverence, will ultimately lead you back to the Creator of all things.

So even R. Crumb should be capable of reverence. That doesn’t make him kind, or pleasant to be around, or someone you’d introduce your daughter to. But it does mean he may be more than a guy who thinks dirty thoughts.

This brings me back to the music Crumb likes; Robert Crumb loves roots music, and for good reasons. (I’m a fan too–but Crumb’s knowledge dwarfs mine). When discussing roots music–blues, jazz, genuine mountain music–you can hear the reverence in his voice; you can see his enthusiasm in his posture. You can see his love and respect in his drawings of obscure and forgotten musicians.

Why does he like roots music so much? Why do those gritty minstrels elicit reverence from him when almost nothing else can? I think there’s more to it than style, I think it is a matter of substance. Roots music recorded real suffering, real joy, real pleasure. It wasn’t “mouse music“. It wasn’t sung just for money. It wasn’t commercial, or canned, or phony. It was music that sprung up from the bottom. It is about the reality of genuine lives lived. That’s something that Crumb can respect, even revere. And this our clue, our hermeneutic for interpreting Crumb, dirty thoughts and all. Crumb wants the truth, warts, or dirty thoughts, and all. Anything less drives him to drawing. And this is the reason I called him a bohemian conservative earlier. Crumb is not a progressive, really. An Adamite maybe, but not a progressive.

Truth verses Exposure

This brings me to the biggest problem with Crumb’s work. He confuses exposure with truth.

Crumb is that kid who turns over rocks to see the slimy, oozing stuff underneath. And that is what Crumb’s Genesis Illustrated attempts to do for us. He wants us to see the ugly truth beneath the sweet surface or the Bible.

He announces his objective right on the cover. “Nothing Left Out!”

At a minimum, there are two big problems here. One that can be attributed to contempt for a literary convention and the second is just stupid malice.

Problem One: Graphic sex.

Someone needs to hand Crumb a dictionary dogeared to the page with the definition for euphemism. When scripture reads, “And he knew her…” or a little more baldly, “He lay with her…” sex is clearly referred to while at the same moment being covered over. This is the sort of thing that Crumb cannot abide. (Yes, his treatment of sexual relations is pretty tame, especially for him. Still, he’s betrayed the text. He has not represented it correctly.)

Some people believe that the only reason you would ever cover-over something as pleasurable as sex is because you believe it is dirty. While I’ve know a few people who do think this way, it is pretty unusual these days. Today we just don’t respect sex enough to keep it covered.

A covering does not necessarily hide a lie. It can protect valuable things. It can even be a way to convey a truth. Euphemisms help preserve the value of sexual pleasure because sex itself can be devalued by overexposure. Like currency, it loses value when you make too much of it. It also says, “This belongs to these people; it is not for you–you may not enter into their pleasures, even vicariously.” Euphemisms can be reverent.

In Genesis, after Adam and Eve sin, it is God who clothes them. In part to cover their shame, but also to adorn them. Paradoxically clothing draws the eye upward to the face, even as it draws the eye to itself. Euphemisms are like clothing in this way. Ironically, Crumb fails here. In his quest to “leave nothing out” he leaves out the euphemisms.

Problem Two: Graven Images.

What’s the deal with the cross between the Sistine Chapel and Charlton Heston?

The argument that since this is a graphic novel you have to draw God, is not an argument for drawing God, it is an argument for not making a graphic novel. Besides, it’s lame.

But I suspect there is more going on in Crumb’s mind than translating the biblical text into a visual form. I suspect that this is what the whole thing is about. Crumb wants to libel God or libel patriarchy, probably both. He wants to expose the hidden agenda of the Bible. “It’s all a evil scheme to promote male power!” It doesn’t take any work arriving at this conclusion. All you need to do is read a few of the many interviews with Crumb about the book that are available online. That, or just turn to the back of his book and read his commentary.

But he gets patriarchy wrong; it is not necessarily hubris, although it can lend itself to that (just like anything else, including drawing comics). It was just necessary, and it still is.

But we don’t even have to defend patriarchy to criticize Crumb’s images of God. Crumb just misses the substance of Biblical revelation in a spectacular manner.

You have to turn a blind eye to received Jewish, Christian, and Islamic teaching in order to do this. You also need to be ignorant of the book that follows Genesis and the prohibition found there concerning graven images. According to the traditions in which Biblical revelation has been reflected upon for thousands of years by reverent intellectuals, you cannot depict a transcendent God visually. That would necessarily locate him in time and space. And it would be a lie.

So again, Crumb errors by adding stuff. And in at least one place it leads to a visual faux pas.

The most disappointing treatment in his whole book is Genesis, Chapter 15. If there were ever a scene just tailor made for Crumb’s style, it is the one in that chapter. But not only does he miss the point of it (I’ll get to the reasons why in my next post), he visually bungles it.

It is the covenant God cuts with Abram. In that scene, I hope you can recall, two signs of God’s presence appear–the burning torch and the smoking pot. (Those should remind you of God’s presence with the Israelites in the wilderness.) But Crumb inserts his oversized version of Charlton Heston into the scene. What’s the point of the torch and the pot when we see him there as something out of the Sistine Chapel? Right, there is no point.

If you detect some anger in my prose it is because I am angry. I’m angry because Crumb is lying to himself and to the rest of us and it is time someone called him out on it.

But how could he miss these things so terribly? I’ll deal with next time in my final post of this review.