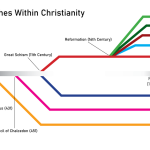

I suspect that both the apologists for Calvinism and its detractors misunderstand its appeal. It isn’t so much the formula of its doctrine that draws people in as its aesthetic. I haven’t thought this through entirely; this is more an impression than any argument. Let me try to explain.

Calvinism has two sides, a side we’re all familiar with, a light-side so severe it hurts the eye, and another side, a shadow-side. It’s on that side that a power hides that draws those who dare to draw near.

As you should know, there’s something biblical about this. Here’s a passage favored by Calvinists but, in my experience anyway, is largely overlooked by nearly everyone else:

The secret things belong to the Lord our God, but the things that are revealed belong to us and to our children forever, that we may do all the words of this law. Deuteronomy 29:29

Those are the sides. A light side, i.e. things revealed, and a dark side, secret things. Each is a side of Calvinism’s aesthetic. Calvinists who’ve fallen from grace tend to land on one side or the other. Emerson and the Unitarians landed in a the land of light. Melville lost sight of the light entirely. (The irony is intended here.)

The Light Side

This side of Calvinism’s aesthetic informs your typical New England meeting house: its crisp, simple lines with bright, unstained windows, and its voids unfilled by the ambiguities of statuary. Everything is intended to reflect a conceptual, almost mathematical faith.

This is because Calvinists take what has been revealed then take logic’s upward way.

And where does that take us? to demanding heights, along severe, unyielding terrain, to a hard land, where the air is clean but cold. Two sorts like it enough to settle here: those blessed with hard, muscular minds, and those who’ve lost faith in themselves. (There are others, but these are not well.)

At the very top loom two peaks. From each you can see that the light of scripture only illuminates two things: the past of God’s work with one people, and the future. A faint, but promising light can be descried on that far horizon. But in-between there is a yawning abyss. This is a place of darkness, a place for secret things.

Vertigo sets in and tender-minds quickly withdraw, vowing never to return. Many, when they get back to a gentle, rolling land, warn others not to follow the implacable logic of the Calvinists.

The Dark Side

Now to the dark-side of Calvinism. Its darkness overshadows the present and even fills those portions of the past not illuminated by scripture. This is the place we live our lives. It is only experienced, not understood, at least not by the formulae of the logicians. In Calvinism, when it is spoken of at all, it is left to the poets.

I’m thinking here of John Newton, William Cowper, John Milton, even Herman Melville. What these men show us is there is something sublime to ignorance, and the darkness can cast its own sort of light.

This has its correspondences in the natural world. Edmund Burke’s writing on the sublime helps here. Something good flows from the crushing knowledge that you don’t know, and can never know things you deeply long to know.

I recall reading in Chesterton somewhere something he said about nature not being our Mother; instead, he said, she is our little sister. Like so much in Chesterton, it is a delightful thought, the sort of thing that would occur to a man who still thinks of the heavens as nesting light-filled crystalline spheres, rolling along harmoniously.

Calvinists belong to the Hudson River School of thought. Nature is immense and indifferent. For a Calvinist nature isn’t a little sister, it is the mighty Niagra and we’re all in barrels without paddles.

The poets of Calvinism see God in these dark things. It is the scale of nature, even its relentless logic and frightening indifference, that reveal the terrors of God. His power overwhelms, his ways are inscrutable, and in it all his glory only intensifies. Scripture is full of this: he a whirlwind (Job 38-41), a dragon (Psalm 18), a shouting wrath-filled giant. (Jeremiah 25).

Take these lines from Cowper’s, God Moves in a Mysterious Way:

God moves in a mysterious way

His wonders to perform;

He plants His footsteps in the sea

And rides upon the storm.Deep in unfathomable mines

Of never failing skill

He treasures up His bright designs

And works His sov’reign will.Ye fearful saints, fresh courage take;

The clouds ye so much dread

Are big with mercy and shall break

In blessings on your head.Judge not the Lord by feeble sense,

But trust Him for His grace;

Behind a frowning providence

He hides a smiling face.His purposes will ripen fast,

Unfolding every hour;

The bud may have a bitter taste,

But sweet will be the flower.Blind unbelief is sure to err

And scan His work in vain;

God is His own interpreter,

And He will make it plain.

A few years back an old college friend of my wife came by for a visit. She was in a bad place. Her husband had come out as a homosexual and had abandoned her. She needed something. Nothing in the saccharine Arminian church she attended could shine any light into the dark place she was in. So we took her to church with us and there she heard this hymn for the first time. After that she just sat through the service with her hymnal open, going over it again and again.

The poets of Calvinism know it is the sublime that gives God’s merciful glance a quickening power. Nice gods don’t raise the dead.

This is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and Job, and Jonah, and even Pascal. This is the Lord, the maker of heaven and earth, and the God of the Bible. And the Calvinists know he dwells in thick darkness.