Chapter Four: The Magic Knot

“Have the courage to conclude.” (Don’t recall where I read that, but it’s good advice.)

Then there’s–

“Begin with the end in mind.” (More good advice, if you can think that far ahead.)

These things are easier said than done. (There’s another truism for you.) But what makes for a good ending? How do you know it when you see it? Ah, that’s the trick.

I’m midway through my middle grade series, two books down and two to go, and I have a confession to make: I just discovered how the story ends yesterday. It’s going to be a good ending, and I believe a very satisfying one, but I had to have the first two books behind me before I could see how book four ends. (I also know how book three ends, thankfully.)

I don’t know why it works this way, but it just does for many authors. Which brings up the whole matter of having the courage to begin when you don’t have the end in mind. So, how do you muster the courage for that?

I think it has mostly to do with knowing what you’re looking for in a story. When you know that, you can recognize the ending when you come to it.

I think this comes as something of a surprise to people who don’t tell stories. I think most people believe stories are things we have complete control over, that they are formed entirely in our heads. But in my experience, and the experience of others, that’s just not the way it works. Endings are discoveries, like coming to a vista after a long hike. When you arrive you say, “So this is what I’ve been looking for!”

For a story to succeed it truly does need to end well. I don’t mean happily, just in a way that satisfies the reader. Etymology is a help here. A text is a weaving. (Think textiles.) When you write, you weave threads together, characters, settings, and so forth, into a plot. When you get to the end, you take the loose ends and tie them up. The magic is in the knot.

Getting to happy endings: I believe Christianity introduced them to the world.

You can’t live happily ever after, you see, if you’re dead. And for pagans, that’s how every story ends.

The Greeks gave us comedy and tragedy. Now what they had in mind when it came to comedy is not what we think of when we think of a rom-com. That’s a happy ending tale. What the Greeks had in mind was a parade of fools. Who’s in the parade? Everyone. We’re all fools because we live our lives by false hopes. The Greeks agreed with Keynes, in the long run we’re all dead. Tragedy just shows us that in graphic detail. And usually the protagonist dies because of some foolishness on his part.

What the Norse gave us is the nobel end. Everyone is still dead, but they die heroically. You see, Valhalla is not an everlasting paradise, it is a pleasant holding cell for the greatest warriors of history. Odin is a assembling his army for the last stand against the forces of chaos. They’ll lose in the end, but they will lose valiantly.

It took the resurrection of the Son of God to give us, “And they all lived happily ever after.”

But the trick is saying that in a satisfying and faith inspiring way. And it is quite a trick.

I’ve been using C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien throughout these essays, and I’m going to do it again. I think when it comes to the happy ending, Lewis gives you the scent of it from a distance and Tolkien helps you recognize it when you see it.

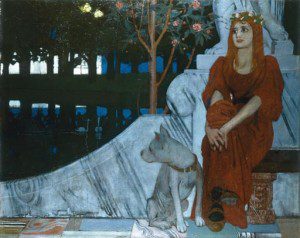

Sehnsucht

——————– D: ——————–

Oskar Zwintscher, Sehnsucht/ 1895

Zwintscher, Oskar

1870-1916.

“Sehnsucht”, 1895.

Oel auf Leinwand, 120 x 150 cm.

Meissen, Stadtmuseum

That unnameable something, desire for which pierces us like a rapier at the smell of bonfire, the sound of wild ducks flying overhead, the title of The Well at the World’s End, the opening lines of “Kubla Khan“, the morning cobwebs in late summer, or the noise of falling waves.

If you’ve felt what Lewis is talking about, you don’t need further explanation. If you haven’t felt this, I can’t help you. It is a longing for something we can only descry from a great distance.

I’m assuming here that you’re a Christian, or at least wish you were one, and you want to tell a story with a happy ending. If you’re not interested in happy endings, if you want to tell a story where everyone is dead in the end, nothing could be easier. The only purpose sehnsucht can serve in that case is for setting up the fool. See Kafka, Sartre, or even Lovecraft if that’s the story you want to tell.

But if the happy ending is what you’re after, you need the longing Lewis is talking about here. But there there is the problem of arrival. It is really tough to do that.

Eucatastrophe

This is where Tolkien comes to the rescue. Lewis does deliver a marvelous ending to The Chronicles of Narnia at the end of The Last Battle, but it took Tolkien to describe just how it is done.

In his marvelous address, On Fairy Stories, Tolkien coins a term, eucatastrophe. It is “the joyous turn” that catches the breath. The thing about it that keeps it from the clumsiness of the standard Deus ex machina plot device is the confluence of elements that swirl together in the end. There’s a miraculous combination of inevitability and surprise that satisfies rather than exasperates. Pulling it off is the trick. Lewis succeeded, so did Tolkien. But I believe J. K. Rowling failed. (That’s something we can talk about another time.)

If you can pull it off, maybe you can join that august assembly of story-tellers. I hope you can. The world would be a richer place for it.