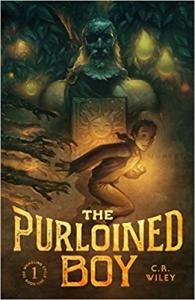

What follows are some concluding remarks to a talk I am delivering at Eastern Nazarene College tomorrow (4/5/18). The whole talk will hopefully be published somewhere in the near future.

Preachers rarely excel at writing fiction. Not many try, but those who do are often accused of preaching under false pretenses.

(For atheists preachers do nothing but produce fiction–we’re the greatest story-tellers of all time. But you know that’s not what I’m getting at.)

Now, I think most of us rationalize away artistic failure. One way to do it is by defining things incorrectly. Here’s an example of how that can work in this case. A preacher who fails with fiction may say, “Well, truth is more important than art. And since I am a preacher, I use my fiction to preach. I am not an entertainer. I would never stoop so low.”

Well, yes and no. Neil Gaiman has some thoughts on this, and while I’m not a fan of his fiction, he’s certainly a bright fellow with many good things to say about the craft of writing.

Here he is in The Guardian.

We writers – and especially writers for children, but all writers – have an obligation to our readers: it’s the obligation to write true things, especially important when we are creating tales of people who do not exist in places that never were – to understand that truth is not in what happens but what it tells us about who we are. Fiction is the lie that tells the truth, after all. We have an obligation not to bore our readers, but to make them need to turn the pages. One of the best cures for a reluctant reader, after all, is a tale they cannot stop themselves from reading. And while we must tell our readers true things and give them weapons and give them armour and pass on whatever wisdom we have gleaned from our short stay on this green world, we have an obligation not to preach, not to lecture, not to force predigested morals and messages down our readers’ throats like adult birds feeding their babies pre-masticated maggots; and we have an obligation never, ever, under any circumstances, to write anything for children that we would not want to read ourselves. Neil Gaiman in The Guardian, Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading, and Daydreaming,

This assumes that we’d never want to consume predigested morals—but I know many, many readers who want nothing but that. Even so, Gaiman is a tad disingenuous here because he’s preaching very forcefully against preaching, which is what you would expect a modern writer to do. But to his credit he wants to tell the truth, and to show us who we are. And this, he tells us, is not compatible with preaching. Fiction is something you should chew on for yourself in order to draw whatever nourishment you can from it. And apparently that’s not what preaching does.

Being a preacher myself I’m more sympathetic to the task. Beside the fact that writing well is harder than it looks, I think the primary reason preachers are often bad writers is because we don’t want people to miss the point. We want them to understand.

Yet, for people who claim to be following in Jesus steps, this is a little odd. Jesus was accused to being obscure and difficult, of not speaking plainly; why, he even told stories where bad guys look good, and good guys look bad. And he once actually said that he spoke in parables precisely so that certain people wouldn’t know what he was talking about.

Jesus didn’t make things easy I believe, in part, because making things easy doesn’t change minds. It merely confirms what people already think, that, or it fails to get past the defenses they erect against things they don’t want to think about anyway. We make things so easy to understand people can see them coming a mile off. When people have to work to understand something difficult their thinking is altered to accommodate it. And the mind never goes back to its original shape. For the truth teller, that’s half the job. The other half is getting people to love the truth. And this is where fiction works supremely well. Fiction is a form of virtual reality that people can safely enter knowing they can leave at any time. And when they sympathize with imaginary people, their new sympathies can go with them out into the real world, the one we all share. Just think of the story of the Good Samaritan.

But we’re still in familiar territory. For an older, and much stranger view, let’s return to Flannery O’Connor, a woman who could write stories as disturbing as those we have from Neil Gaiman, yet which leave you in a very different place than Gaiman would have you go.

According to O’Connor the form of the story cannot be separated from its truth.

I prefer to talk about the meaning in a story rather than the theme of a story. People talk the theme of a story as if the theme were like a string that a sack of chicken feed is tied with. They think that if you can pick out the theme, the way you pick the right thread in the chicken feed sack, you can rip the story open and feed the chickens. But this is not the way meaning works in fiction. When you can state the theme of a story, when you can separate it from the story itself, then you can be sure the story is not a very good one. The meaning of the story has to be embedded in it, has to be made concrete in it. A story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate.

There is something profound here. We tend to think that propositional truth is truth’s highest form rather than a mere distillation of it. Abstraction abstracts. It tries to remove the essences of things and leave their husks behind. That begs the question of what language is, though. What about words, and how do they carry their freights? Is language a kind of trick, leaving us with images but nothing real? Or can words communicate reality itself. When John said “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” he was getting at this. You cannot abstract the truth of Jesus from Jesus. He is the Word, and he is God, at the same time.

Paradoxically, a story can be closer to the truth than a proposition is. I suspect that’s one reason that people perk up when the stories begin. I’m certainly not against propositions. I’ve been using them my entire life. But they simplify things. That’s their genius. If we had nothing but stories we might feel the meaning of our lives more acutely, but we’d also have shorter lives. My only objective here is to knock the proposition off its perch as the best way to tell the truth. The gospel is a story, after all, not a proposition, not even four of them.

I am now at high point of my argument. This is precisely so because stories get us closer to the ground. Stories, like people, rise from the soil of creation. That’s why they can reveal things. As Flannery O’Connor said, it is through a story that you see a theme. And that can only be so because the world as a whole, with all of its many parts, gives us our words. And the world contains a theme: the glory of God.

It’s all in Psalm 19, all in Psalm 19, what do they teach these preachers in these seminaries? The preacherly story-teller, even when he writes a fiction, if he does it well, tells a story that will preach. It may even help him employ propositional truths.