“O God, to whom vengeance belongeth, show thyself!” Psalm 94:1

I know a man who abandoned his children in a house with no heat on a bitter January day. He didn’t speak to them for years. And when he did, he never apologized, he just explained. Today he insists that he has loved them all along, love being a warm feeling that fills his precious heart whenever he thinks of them.

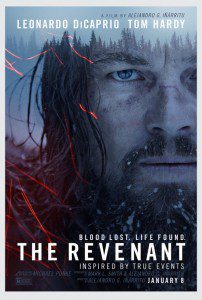

The Revenant is about a very different sort of father; correction, two such fathers.

I don’t talk about love much anymore. Odd for a preacher, I know. The word has lost so much of its old power. Overuse and misuse are partly to blame, me thinks. There’s the warm-hearted worthless father of a moment ago, but there’s also the cosmopolitan who loves everyone in general and no one in particular.

I speak of loyalty instead. Almost no one talks about that anymore. It’s rare and valuable. That’s why we still treasure it.

The Revenant is a story of loyalty, and almost by necessity, betrayal, and revenge.

Technically the film is magnificent. The cinematography immerses you in the unforgiving wilderness world of trappers and native Americans in the first half of the 19th century. But I’m not going to spend any time on that side of things because I suspect the reason the studio wanted Patheos writers to screen the film is because we can bring something else to the analysis of the story.

Here’s a few things you need to know. To call this film “entertaining” would be to degrade it. Taken in properly, it should be received with reverence and reflection. At the screening for the press that I attended, when the lights came up, there were two responses. The first, stunned silence. The second, chirpy talk like this: “What did you think of the bear?” or “How would you rate Hudson’s performance?” Maybe that’s the price paid for being a film critic, but it may be just another way to change the subject. Don’t be like those guys.

Second, the film is violent, I’m talking Braveheart violent. But it isn’t gratuitous violence. I think it is integral to the story. Without it you can not sympathize with the fear, and the anger, and the drive for vengeance that make the story.

Finally, you’ll note from the trailer that the film is inspired by true events. Hugh Glass was a real trapper and guide, and I was familiar with his story before hearing of the film. If you’d like to read up on him, here’s the wiki page– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Glass

It was a tangled world (and still is),

If you’re looking for a Dances with Wolves, Native Americans = good guys, white men = bad guys story, you won’t get it here. The real world is more complicated than that, and the film tells the truth. The tribes warred with each other, as well as with whites. The whites warred among themselves, the French still had a strong presence in the region at that time and resisted incursions by Americans. And the French and the Americans were allied with different tribes.

Throughout the film we pan out to see the big picture, and then get in close to see the faces of people in a crucible. The spine of the story is the devotion of two fathers to their children: Hugh Glass, American trapper and guide to his half Pawnee son, Hawk; and an Arikaree or Ree, chief to his daughter. Against these loyalties there are many betrayals, some small, some on the order of Judas.

After being mauled by a bear, Glass (played by DiCaprio) helplessly witnesses the murder of his son by fellow trapper, Thomas Fitzgerald (played convincingly by Tom Hardy). After Glass is abandoned for dead, he manages to scratch and crawl his way back to the nearest American settlement, 200 miles away, motivated by a desire for vengeance.

The Ree chief, who was responsible for a raid on Glass’s trapping expedition at the very beginning of the film, is out to save a daughter he mistakenly believes was stolen by the Americans. Later we find that she had actually been abducted by a French expedition ostensibly allied to the Ree,

These two quests interweave throughout the film and providentially each father helps the other come to the end of his quest.

Where God comes in

It wasn’t until I was about of a third of the way through the film that I understood the reason why Patheos writers were invited to the screening. What I had thought was just another survival story became one of the most theologically rich films ever made.

To talk about that I’ll need to give away some things. So if you’re one of those people who hate spoilers, stop here. Come back later to see what you think about my reflections. You’ve been warned.

I won’t be long, and I’ll only focus on three scenes.

The ruins of the mission church

Throughout the film Glass has flashbacks to the massacre of a Pawnee village by what look to be the French. He loses his wife in the attack, almost loses his son, and hints are made that Glass kills an officer in the process. Glass also has visions of his deceased wife in which she repeats, and I’m paraphrasing here: “When the storm comes, don’t look at the branches of the tree, look to the trunk.”

During his torturous trek back to the settlement he has another vision. This time of the ruins of a Catholic mission. The walls are covered with sacred art, and behind the altar there is the crucified Lord. Standing before it is his dead son, Hawk. Hawk had come upon Fitzgerald when he was attempting to suffocate Glass not long after the bear attack. Hawk had intervened, but he was too weak to overcome Fitzgerald. To cover up his attempt to murder Glass Fitzgerald kills Hawk. As you can see from the trailer, Glass witnesses the murder but he is too weak to intervene and he can not speak.

Hawk, the son, sacrificed himself so that Glass might live. In his vision Glass embraces Hawk only to find that Hawk has become the tree his mother spoke of.

To say anything more would rob the scene of its power.

God is a squirrel

After killing Hawk and abandoning Glass, Fitzgerald is accompanied by the unknowing Bridger, a young and compassionate man played by Will Poulter. Bridger didn’t see what became of Hawk and he feels tremendous guilt at abandoning Glass; but he cannot match the physical strength or ruthless energy of Fitzgerald. He is taken away against his will.

Fitzgerald begins to theologize along the way, partly to excuse his own betrayals by presuming upon the providence and grace of God, but in the process he reveals something else.

During a fireside conversation Fitzgerald reminisces about someone he knew who found God while struggling to survive in the wilderness. “God,” Fitzgerald recounts the man saying, “…is a squirrel. So, I ate the son of a bitch.”

The chuckleheads throughout the theater sniggered at this. But considering the sophisticated handling of theological themes I was witnessing, I couldn’t attribute this to the kind of juvenile posturing we see among those “new atheists”. I couldn’t help but wonder if Fitzgerald was saying more about himself than God, and Caiaphas-like, saying something true about the ways of divinity nonetheless. God is elusive, he hides, he’s difficult to catch, yet he is our food.

Vengeance belongs to the Creator

Toward the end of his seemingly interminable journey, Glass comes upon a lone Pawnee warrior named Hikuc (played by Arthur Redcloud) who has managed to chase a pack of wolves off from the the carcass of a buffalo. Glass, knowing Pawnee, begs for some of the food and Hikuc has mercy on him.

We come to learn that Hikuc lost his family to a Sioux raiding party, so he identifies with Glass’s losses. But he reveals that he has left revenge to God: “Vengeance belongs to the Creator.” This serves as our interpretive clue for understanding what comes next.

After Hikuc applies Pawnee healing arts to Glass’s wounds, he builds a shelter for him against an impending snow storm. The next morning Glass awakens to find Hikuc gone. Food has been left for him. But not long after setting out, Glass finds Hikuc dead, hung from a tree with a sign in French around his neck.

Glass finds his way to the French camp and in the course of stealing a horse he stumbles upon the missing Ree princess while she is being raped. Glass frees her and then escapes.

Mysterious are the ways of the Squirrel. Glass finds a nut and ultimately it will save him, but it will also lead to Fitzgerald’s death.

Glass and Fitzgerald meet again

When Glass finally returns to the settlement, he is greeted by the other surviving members of his original party as a man who has come back from the dead–the revenant. Fitzgerald flees and Glass pursues. But Fitzgerald is nearly as wily a woodsman as Glass and the final confrontation must be seen for oneself.

But in the end, the Squirrel gets vengeance.