I recall a conversation with a young author years ago. We were having lunch in a restaurant and in the course the conversation I asked him to tell me about his book. He told me his hero (a human being, it is important to know) had been hatched from a dragon’s egg.

I started feeling ill, not because of the impossibility of the thing, but because I knew he had no sense of what that meant, not just in my opinion, but as a point of fact. Oh, and later he told me he didn’t like Tolkien because the man had been Catholic, no other justification, that was enough. I was glad when the meal was done and we went our separate ways. The guy had creeped me out.

There’s been a little dust up recently in Reformed circles. First Things republished something on its blog that Peter Leithart had written a decade or so ago about why evangelicals can’t write anything beside academic prose. (Here, and again here.) He blames it on our sacramentology, or lack of it. This led to a rear-guard action of academic prose by others that amounted to correlation doesn’t imply causation.

I find myself in the awkward position of partially agreeing with both sides. And the reason this is so is I think Leithart has confused cause and effect. Evangelicals don’t get the sacraments, and many of them can’t write, because they don’t believe metaphors have any basis in reality. They think the world only refers to itself and metaphors exist only in our heads. Here’s another way to say it: evangelicals largely think metaphors are invented, not discovered. (And I’ve known plenty of Catholics who would agree, secularists too, it goes without saying.)

The World Is a Poem

I heard a report on the BBC about a poet drawing a crowd of 40,000 in Afghanistan and I thought, how remarkable. Clearly they see something in poetry that we do not. I think that’s true for most cultures untouched by the Industrial Revolution. For those people the world is still an enchanted place, and poetry draws us into its spell.

Most Christians until recently believed the same thing. (Gospel really is God’s Spell.) Christians still say they believe that the Word of God gives our world its form, but I’m not sure they really do believe that anymore.

Christianity says that the world is a poem and it refers to something. (The word comes from the Greek, poema, literally, to create.) Historically it was thought the poem had an inner consistency, a sort of cross-reference system, lower things pointing to higher things, visible things to invisible things. This is why a dragon always meant something objective, even though we don’t have any physical dragons. (It’s a composite image, a blend of things in the physical world that amounts to a spiritual disease.) And this is why my young interlocutor was so disturbing. He was like a kid with a chemistry set mixing toxins–but his chemicals were words and the toxin was his story.

Ps. 42:7–deep calls to deep

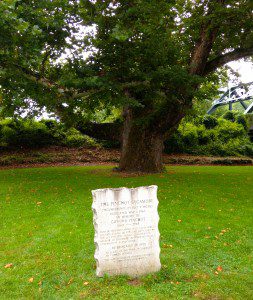

How does this work in practice? Because creation echoes, we can find harmonies in it, things that agree with each other. For example, did you know the words tree and truth both have the same root in middle English? The word troth–as in betroth.

Well, why should that be? Use your imagination a little, go ahead, it won’t mislead you here. Trees are what? Big, right, and strong, and useful, and living. Truth, a concept that’s more than a concept, harmonizes very well with this. The two things speak to each other. But people didn’t start with the concept of truth all alone, and go looking for a metaphor. The concept probably grew up in their minds as they saw, and touched, and heard, and smelled, and tasted the world all around. Truth, in its most rarefied form, was discovered as people drew comparisons between social life and the physical world. Trees helped some people discover truth.

Why should this surprise or offend us? The Bible informs us that you and I are living metaphors–we are images of God. We’re not real in the same sense God is, the reality we enjoy is derived from him. And those subsets that some adamantly maintain are nothing but social constructs, also mean things: maleness for instance or femaleness, childishness and so forth. Our freedom is not absolute, we’re given things to work with.

And that’s the offense, we wish to be like God, knowing both good and evil, in other words, by defining those things. For all the talk about scientific progress and political freedom, I can’t help but think we’re trying to shout God down.