Note: All opinions expressed on this blog are my own and do not necessarily express the stance of the General Church of the New Jerusalem or any other organization.

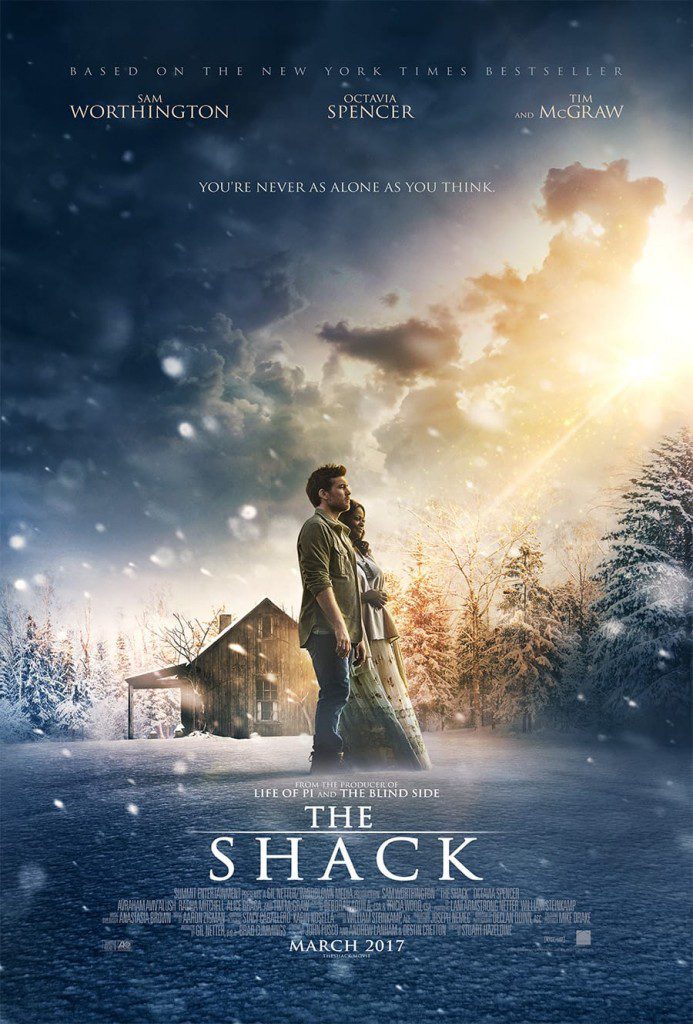

I went to see The Shack, a new movie based on the runaway bestselling Christian novel, intending to watch it from a dispassionate theological perspective – critique its view of the Trinity, maybe, and explore its theology of suffering. But early on I found myself being drawn into a story that hit me viscerally, in ways both good and bad. In the end I came away torn – there are so many things in this movie that I loved, and only a few that I found to be genuinely bad. But the bad hurt enough that I don’t think I’ll be watching this movie again, and for all the good it may do for people who are hurting, I don’t think I can recommend it in good conscience.

First of all, a caveat: I don’t plan to review this movie as a typical movie critic would. For one thing, that’s not my job and I don’t think I’d be very good at it. For another thing, in some ways this movie is more of an extended narrative sermon than it is a traditional movie. It’s getting some criticism for that, but it’s worth pointing out that people seek out good sermons and love to hear good preaching. “Sermon” doesn’t have to be a dirty word. In this case I think it’s a pretty apt description. As such, I don’t feel a need to pick apart the acting and dialogue any more than I would want someone to do the same with the illustrations in my sermons. That’s not really the point.

That said, here’s what I liked, what I didn’t, and why I’m torn about the film despite all that’s right with it.

The Plot

The first act of The Shack is pretty grim. We’re introduced to Mack: a boy who is beaten and abused by his churchgoing father. At age 13, Mack mixes strychnine in with his dad’s booze, and kills his father.

From there, we flash forward to a glimpse of Mack’s adulthood, and his happy life as husband of Nan and father of three kids: Kate, Josh, and young Missy. But we’re told (by Mack’s friend Willie, who narrates the film) that the happiness didn’t last. A great sadness came over Mack. During a snowstorm, we see a despondent Mack – clearly struggling with some kind of grief – tromp out to borrow gas for his snowblower from Willie. On his way back into the house, he finds a letter in the mailbox from “Papa,” Nan’s name for God, inviting Mack to meet Him in “the shack” the following weekend.

What is the shack? Why the great sadness? We learn in a flashback: during a camping trip, Mack lost sight of Missy, and she was presumed abducted by a serial killer who left his calling card. Days later, they found the site of her murder – a shack near the mountain lake where they had been camping.

We flash back to the present. Mack decides to go back to the shack at the invitation of the mysterious note. When he gets there, he finds the last thing he expects: a matronly black woman who calls herself Papa, a middle Eastern man who is her son, and Sarayu, an Asian woman described as “a whisp of breath or air.” In other words, the Trinity. The rest of the movie is an exploration of Mack’s struggle to reconcile the concept of a good God with what God allowed to happen to Missy.

As I said, I wasn’t expecting to be drawn into the story and the plot, but I was. I’m sure a lot of that has to do with having two young kids of my own. It wasn’t hard to identify with Mack in his terror, then in his grief and anger. Granted, having a child abducted can be a bit of an emotional shortcut, but it did what it needed to do to get me out of my overly analytical head and into my heart for the rest of the film. (And for what it’s worth, there’s not much in the way of blood or gore, and no jumpy shock scenes – this is not in any way a horror flick.)

The Good

It avoids easy answers and instant fixes

Christian pop culture has a tendency to jump too quickly to the anodyne positive message or the quick fix. This movie admirably avoids that – Papa even tells Mack directly that there won’t be any easy answers or instant fixes. The movie treats pain with respect: as something to be dealt with and eventually overcome, but as something real and powerful, not to be done away with lightly.

The same holds true when it comes to messages of forgiveness and reconciliation. Even when one character comes to the point of saying, “I forgive him,” he confesses to Papa afterward, “I’m still angry.” Papa’s response: “That’s the way it is; you might have to do it a thousand times before it gets easier.”

It doesn’t shy away from the hope of heaven

Even though it doesn’t jump to any easy answers, the film explicitly holds out the hope of eternal joy in heaven. I suspect some reviewers will call this a cop-out, a shortcut out of grief. I don’t see it that way – the grief and pain are still real, the separation still hard, even if it is seen as temporary. And a Christian movie would be dishonest if it didn’t point to this hope as part of the answer to God’s permission of evil.

It clearly states that God does not cause evil

Another key point I appreciated: a very clear stance that God permits evil but does not will it or cause it. The film avoids getting entangled in the details of exactly how that works, but God gives the message again and again: I did not cause that evil, that evil caused me grief, but I was there through it and I will bring good out of it.

It shows God as free from wrath

At one point, Mack asks Papa about wrath: “That’s when you punish the evil, right?” Papa flat-out denies it: “That’s not who I am.”

It’s a statement that I suspect will give fits to some theologians and pastors – there is no attempt to address the fact that the Bible very clearly does talk about God’s wrath. But as someone who does believe that God is free from wrath (as humans understand wrath), and that such a statement can be reconciled with Scripture, I’m happy to hear those words put in God’s mouth, if only for the conversation it can start. (And as I’ve written before, if the earliest Christians could speak of God as “free from wrath,” I think we can too.)

It shows a united God

Here’s the part of the movie that I was most pleasantly surprised by, and that I think has the greatest potential for good. When Mack first meets Papa, he confronts her about her indifference to Missy’s suffering – and her apparent indifference to her own Son’s suffering. “It’s not like that,” Papa explains, and reveals marks on her own palms. When one suffers, all suffer. (I don’t mean to imply that I subscribe to patripassianism – I don’t – only that I appreciate the emphasis on unity of purpose and will.)

The characters of the Trinity go to great lengths to emphasize their unity – there is no wrathful, judgmental Father who is at odds with a merciful Son. God – all of God – is love. If there is one simple message to this film, that is it; as Papa says to Mack, “The real underlying flaw in your life that you don’t think I’m good.” This movie affirms: all of God is good, and all of God is there even in the suffering.

The Bad

A false dichotomy between obedience and friendship

With all those positive points going for the movie, what could I have against it? A few things. The first is a relatively minor part of the plot, and so I could let it slide even though it annoys me. At one point, Mack is talking to Jesus about religion – what about following the rules, being a good Christian? Jesus dismisses the idea, saying, “I’m not interested in slaves – I want friends.” While the first part of the statement is an admirable affirmation of how much God values freedom, the statement as a whole reflects a false dichotomy between religion and relationship. Jesus did call His disciples “friends,” as recorded in the Gospel of John:

No longer do I call you servants, for a servant does not know what his master is doing; but I have called you friends, for all things that I heard from My Father I have made known to you. (John 15:15)

But it’s a mistake to read that verse without first reading the verse that immediately precedes it:

You are My friends if you do whatever I command you. (John 15:14)

Jesus does not want slaves – but He does want disciples who will willingly obey His commandments.

The Elephant In the Room

A Trinity of Persons

I hope it’s clear by now that I found a lot to love in this movie. But this last point was the sticking point – and it was enough of a sticking point that I do not plan to watch the movie again. Simply put, it makes me physically uncomfortable to see God portrayed as three individual people interacting with each other. This isn’t about whether God the Father should be portrayed by a woman or a man, by an African American or an aboriginal Canadian. This is about the idea that the Father can ever manifest Himself as someone other than the Son. The founding premise of New Church doctrine is that the Trinity is not a Trinity of the separate persons, but a Trinity that exists within the person of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Now I do think that the Lord Jesus Christ, God in human form, can manifest in different appearances; His appearances to John on the Island of Patmos, with long white hair and fiery eyes, was probably different from His manifestation to Mary on Easter Sunday. But to assume that the Father takes on one form and the Son another, and that these two forms then interact with each other, is to make two separate gods. The Son is the form of the Father. The Father is the invisible, infinite love; the Son is the visible manifestation of that, the Word, Wisdom, the Truth. He is, in the words of Paul’s letter to the Colossians, “The visible image of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15). To think that Love can manifest on its own without doing so through Wisdom – I believe that is contrary to everything we’re taught about God.

The problem with splitting up God

Does it really matter, though? Isn’t this kind of abstract theology secondary to the main point, that God is love? Here’s why I think it matters. First, we’re called to love God, to be in a relationship with God, to be linked with God. We can do that with an individual – with the Lord Jesus Christ. If our picture of God becomes divided, we lose the immediate, one-on-one nature of our relationship with Him. As mentioned above, this film does at least avoid the mistake of assigning radically different personalities (wrathful vs. loving) to the different persons of God. But if they have the same personality and characteristics – why picture them in three bodies? And, on the other hand, if they have different personalities and characteristics – in what way can you say they are one God with whom you have a one-on-one relationship?

Does God love God, or does God love people?

One other big problem with an idea of God as three individuals who interact is that it changes the locus of God’s primary relationship. And this is a fundamental problem I have with almost all Nicene Christianity, not just this film. For many tri-personal Trinitarians, the primary relationship in God is of God with Godself – the Father loving the Son, the Son loving the Father, and that love manifesting as the Holy Spirit. In The Shack, you see this kind of dynamic when Mack and Jesus return from a walk to see Papa and Sarayu dancing joyfully together in the kitchen, rejoicing simply in each other’s company apart from a need for anyone else. Such love between the persons of the Trinity (the thinking goes) is so great that it cannot be contained, and it spills over into a love for humanity, and an invitation to participate in that intra-God love. In this dynamic, a person’s primary participation with God’s love is not directly connected to love for other people, even though love for God does call us to love other people.

You can find some grounding for this perspective in Scripture; in John 17, for example, Jesus prays for his disciples:

Father, I desire that they also whom You gave Me may be with Me where I am, that they may behold My glory which You have given Me; for You loved Me before the foundation of the world. (John 17:24)

But I think this is best understood in light of the opening words of John:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. (John 1:1)

Why does the Father (i.e. Infinite Love) love the Word? Think about what “the Word” implies. A Word is something spoken to someone else. The Word is God’s manifestation to His creation. The Word is valuable because it brings about communication between the speaker and the receiver. If the Word is not a separate individual, but rather refers to the wisdom and manifestation of God – then God’s primary love is not a love within Godself, but a love for something outside of Himself. The primary relationship of God is His relationship with His creatures, and in particular, with the creatures who can love Him back and be joined to Him. In this framework, to participate in God’s love is entirely to participate in a love for human beings. That’s why love for God and love for the neighbor are inseparable:

Beloved, let us love one another, for love is of God; and everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. He who does not love does not know God, for God is love. (1 John 4:7,8)

So – should you watch this movie?

I hesitate to say whether anyone “should” or “shouldn’t” watch any given movie; it seems a bit patronizing to suggest that it was OK for me to watch it for this review, but not OK for someone else to go see it for themselves. But what I’ll say is this: despite the overwhelmingly positive and healing nature of its primary message, the depiction of the Trinity is too much for me. I don’t think I’ll watch it again, and I won’t suggest New Church members go watch it. Despite the good in the movie, I just can’t escape the fact that New Church doctrine condemns a tri-personal God as the great failing of the Christian Church, the mistake that set Christendom on a trajectory for corruption and eventual collapse. To take just one passage from True Christian Religion:

It is a notable fact that several months ago the Lord called together his twelve disciples who are now angels, and sent them out throughout the spiritual world with orders to preach the Gospel there anew, since the church the Lord established through their ministry is today so close to its end that hardly any remnants survive. This has come about because the Divine Trinity has been divided into three persons, each of whom is God and Lord. As a result the whole of theology, and so the church which is named Christian after the Lord, has been pervaded by a kind of insanity. I say ‘insanity’ because it has driven people’s minds to such a pitch of delirium that they do not know whether there is one God or three. One is what they say, three is what they think. So there is a conflict between the mind and the lips, the thought and its expression, and this conflict ends by their thinking that there is no God. (§4)

For whatever merits it may have, I cannot embrace a movie that reinforces so fundamental an error about who God is. But I can understand how someone might see it differently, given all there is to like here.

UPDATE: After hearing from a few people whose lives were profoundly affected by the book, I think I should make this clear: if you are in a desperate place, angry at God, drowning in grief and pain – this movie (and/or book) could be a life saver. It’s that powerful. I’ve explained already why I think the portrayal of the Trinity is not just inaccurate but also harmful; but the dynamics of the Trinity are not the primary point of the movie, and if you’re able to set that part aside, this film might be a place where you start to find healing.

(Photo Credit: Lionsgate. Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.)