When I taught Spanish in public school I projected Hispanic and Latino artwork on my pull-down screen and had students journal or make comments for a daily grade. Initially, the still worlds of painted color intimidated my media loving students, and they complained.

When I taught Spanish in public school I projected Hispanic and Latino artwork on my pull-down screen and had students journal or make comments for a daily grade. Initially, the still worlds of painted color intimidated my media loving students, and they complained.

“How am I going to use this painting in the real world?”

“This isn’t art class.”

“Can’t you just give us a worksheet?”

“We’re going to study it silently for five minutes, then make three comments in Spanish,” was my answer.

“It’s ugly. It’s hard. It’s weird,” someone called out every year.

My students were not stupid, but they lacked the practice required to see.

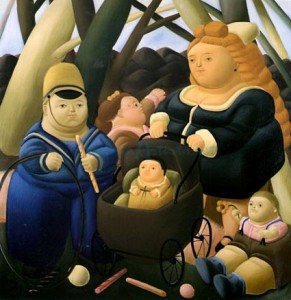

I learned to start the unit with Fernando Botero, a contemporary Columbian artist who paints everything rotund, enormous, and downright fat. Even unmotivated and bored students loved to make judgments on the appearances of others, so we’d get the conversation going with one word: gordo.

Rony, an immigrant from Honduras, took my Spanish course because it was an easy A. He scooted in daily, just before the bell, and flashed me a brilliant smile as he shook my hand at the door. He chatted constantly with a pretty girl who sat next to him, and I frequently had to prevent him from “helping” other students on quizzes.

He took one look at Botero’s Niños Ricos and rattled off three comments for his grade: “There are three kids and a nanny. They’re wearing old-timey clothes. They’re fat,” he said in Spanish, leaning back and grinning ear to ear.

“He’s taking all the easy ones,” a girl said, rolling her eyes. “I was going to say those! That’s all I know how to say.” The rest of my students grumbled in agreement.

I looked back at Rony and raised my eyebrows.

“Ok,” he said and took a breath. “Maybe the artist paints these people fat so that you have to think about how everyone would look if they were fat. And then it’s like no one is fat, and we all just see each other for the beauty on the inside.”

I was the one smiling this time and noted Rony’s grade.

Down the hall, my friend Kim Alexander taught Rony and one hundred other immigrants English as a Second Other Language—ESOL. Like Botero, Kim is also a painter, and in honor of her students she has a series of paintings entitled “The Young Immigrants.”

Like Botero’s fat people, most of Kim’s students are not truly seen in our country. They don’t play football, they rarely make the honor roll, and they’re usually too poor to be fashionable. Some of them are in gangs, are teenage parents, or don’t wear deodorant. Their whole sub-group grieves the annual statistical analysis compiled by the public school system because when you try to work their problems like equations the answers often fall below standard.

And though Kim is required to test and tally scores for her students, she knows that she can’t strip Rony and these other children down to slender, pale, creatures of transparency. Like Botero, Kim understands that people are gargantuan, rotund, and strange, so she accepts their complexities and then translates their beauty using acrylic on canvas.

Yet despite Kim’s gifts, the beauty of these students is not instantly apparent even to her. She must practice using her vision on a daily basis. Waiting, sometimes months, until she finds something extraordinary in each child, and files it away in her heart.

Then she uses that small moment to help her love each one.

It is only because this vision is her practice that she can show it to the rest of us through her craft.

Similarly, my students grew to appreciate the paintings we studied; and by the end of the unit their commentaries switched entirely.

“How come we’re not doing a painting today?”

“Señora, we studied Picasso in my geography class, and I already knew what cubism was!”

“Did you know there’s a mural at the rec center?”

Seeing really was possible.

Last summer, Rony Parada died while trying to save his younger brother from drowning in a lake during a sudden storm. Despite the danger, he dove bravely into the crashing waves and was pulled under. Divers recovered their bodies and journalists told yet another story about young immigrants who didn’t make it in the United States.

But before he died, Rony showed truth to each of us in that class. We practiced using our vision together. And for that small moment we could truly see.

He was beautiful.