The current issue of Image (#75) is full of rich mini-essays on some of the key words we rely on when we speak about the intersection of faith and the arts. Among these words is beauty, which novelist Erin McGraw chooses to parse.

The current issue of Image (#75) is full of rich mini-essays on some of the key words we rely on when we speak about the intersection of faith and the arts. Among these words is beauty, which novelist Erin McGraw chooses to parse.

McGraw’s main point is that beauty is ever-fleeting. We want to get a grip on it; yet by its very (transcendent) nature, we can’t.

I see what she means, and I delight in her brilliant, breezy prose. But I think there’s something important about beauty that McGraw is leaving out.

As her “rough and ready definition of beauty” she offers: “some display of harmony, intelligence, and genius.” I’d go along with this definition as far as it goes—but I don’t think it goes far enough.

Specifically, it leaves out beauty’s moral dimension: goodness.

Remember the Gospel story of the woman who anointed Jesus’ feet with costly perfume? When Jesus’ disciples object to the waste, he rebukes them by saying “She has done a beautiful thing for me.” In the accounts in Mark (14:6) and Matthew (26:10), the Greek word for beautiful is kalon, which has a marvelous range of meaning.

Literally it does mean beautiful, but throughout the original Greek New Testament this beauty can apply to physical appearance or to moral behavior: that is, kalon can mean lovely or free from defects; but it can also mean praiseworthy, morally good, desirable, blameless.

So this very passage is sometimes translated, aptly, “She has performed a good service for me.”

A few years ago, my husband and I wrote a book called Reclaiming Beauty for the Good of the World: Muslim & Christian Creativity as Moral Power. The book’s thesis is that at the core of each of these faiths is a vision of beauty that manifests itself in beautiful works—works not only of art but also of life.

We argue that beauty as conceived by both Christianity and Islam is a moral category, not a merely aesthetic one. It is inseparable from goodness.

As profound and wide-ranging as McGraw’s essay is, she limits her concept of beauty to art and nature. “Beauty,” she writes, “doesn’t generally rouse us to action, unless we feel it edging away from us.… It’s the rare occasion that beauty lights a fire under us to dust the living room or start a nonprofit.”

Those two examples are fun, but I’d put housecleaning and starting a nonprofit in different categories of action. Starting a nonprofit can have a moral dimension which housecleaning lacks (unless I believe that cleanliness is next to godliness—which I don’t).

For instance, the founder of Bread for the World, Lutheran minister Arthur Simon, was embarking on a beautiful enterprise, one that has improved the lives of countless people.

There is, in other words, an art of life. And what is it? Beauty in action.

A key quality in Islam is ihsan, which means beauty—but particularly the beauty that is spiritual virtue—what Islam frequently calls “transparency of heart.” The person whose heart is transparent to God’s gaze acts always as if she were face-to-face with God.

Christianity envisions beauty’s inherent link to God and to goodness differently, of course. For Christians the living God, the Resurrected Christ, dwells through the Holy Spirit within each person. The more we let God’s life live through us, the more beautiful and good are all our works.

Yet Christians can comfortably concur in the statement of Islamic scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr that “The goal of human life is to beautify the soul through goodness and virtue and to make it worthy of offering to God Who is the Beautiful.”

One surah of the Qur’an even puts this as an imperative: “Act beautifully, as God has acted beautifully towards you” (Sura al-Qasas 28:77).

And how has God acted beautifully? Christian artist Makoto Fujimura, known to the Image community, said in an interview that his painting technique is inspired by the beauty of God’s extravagant generosity.

Then there’s the beauty of self-sacrifice and forgiveness. As modeled by Jesus on the cross, this beauty is at the heart of Christian faith.

Inspired by God’s beautiful actions (whether self-sacrifice, mercy, forgiveness, or extravagant generosity), we can be moved to act beautifully ourselves.

Think of the classic film Babette’s Feast. Babette’s generosity, in using her money to prepare a feast which is a foretaste of the heavenly realm awaiting us, moves the previously dour and bickering dinner guests an infinitesimal bit closer to the heavenly ideal of reconciling love.

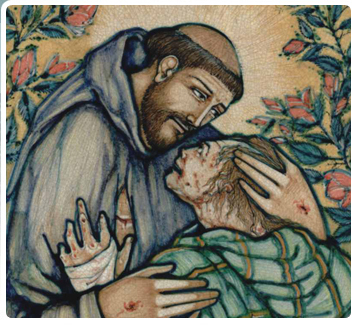

For Christians, a favorite human model of beautiful action is St. Francis. Iconic is his impulsive embrace of a leper he passes on the road.

Scott Cairns’ poem “The Leper’s Return” depicts the efficacy of this beautiful action: its transformation of the leper’s own soul from self-hatred to joy. In the poem, after receiving Francis’s unexpected embrace, the leper

found forgotten light

returning to his eyes, and looked to meet

the brother light approaching from the young man’s

beaming face. Each man blessed the other

with this light that then became the way,

thereafter, each would travel every road.