Not long ago, I had surgery. I suppose that in the vastness of creation, the precipitating problem wasn’t much; with age I’d lost peripheral vision due to drooping eyelids. For several years I’d lived in shadow, sight obscured by canopies of flesh.

My ophthalmologist prescribed blepharoplasty coupled with an endoscopic brow lift. If I chose to have the surgery, he’d put me under general anesthesia, incise along my eyelids’ natural creases and in several places in my scalp. He’d remove excess skin, muscle, and fat and close the gashes with myriad stitches. The procedure would take about two hours, healing, four to five weeks, after which—he hoped—my field of vision would appreciably improve.

When I woke up in recovery, my body tensed with terror, my eyes and head pulsed with pain. I could scarcely press open my eyelids—was anybody there? I felt my husband’s hand in mine, heard a nurse calling my name, but saw only an under-ocean swirl—searing light, floating glow-spots, miasmatic silhouettes. Had my surgeon blinded me?

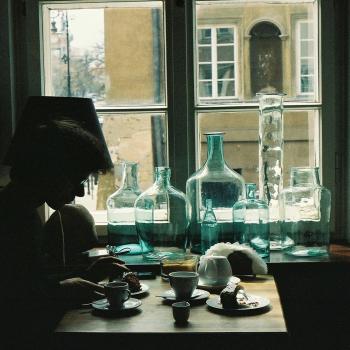

The first few days at home, I lay supine on the couch—inert—ointment in my closed and crusted eyes, pads on my livid lids, bandages round my throbbing head, heavy icepacks on my face. And for some reason I still don’t understand—anesthesia, pain medication?—I lost control of my thoughts, which tumbled into pondering my past, spiraled into panic for the future, pummeled me so relentlessly that my physical black and blueness paled before the bruising of my heart.

For the previous several years, I’d been teaching writing as an adjunct professor at a college. There, I’d given my all to my students: I’d worked fifty hours per week, developed multiple curriculums, written numerous student recommendation letters, counseled students outside of class, led a Bible study cadre, been a reader for senior projects.

Still, I’d been fired by mass email every June, rehired last minute each quarter, paid less than baristas earned at Starbucks, offered no office, meeting invitations, health insurance, or other benefits. And just before my surgery the college had informed me that a brand new PhD would take over my favorite writing class.

So I brooded: How could the college discard me? Had I done something wrong? Was I a terrible teacher? Was the problem my age? I was twice as old as my replacement, who wouldn’t need blepharoplasty till I was in my grave.

Curled up on the couch, I wept through my ointments and dressings, tears coursing into my ears. In my blinded and mummified state, I couldn’t shake my melancholic thoughts. So desperate was I to divert them, I flouted my surgeon’s orders; I picked up a book from the coffee table though he’d forbidden me to read for at least a week.

Straining to open my eyes wide enough to see, I turned to a meditation by the poet Scott Cairns, who wrote of hiking through Utah’s Arches National Park. Having gone only a little way along the trail, he was awed by the endless blue sky, enormous canyon spaces and tremendous arches and towers of incredibly red rock. He stopped to look down. A flash of vivid color caught his eye, held it, and he was startled to see a brilliant, deep magenta cactus flower on a prickly plant whose scarred, paddle-shaped appendages seemed more dead than alive. He wrote:

And then, having noticed that one flower…my eye was thereby led to another just beyond the first, and then just beyond the second, another…brilliant flowers dotted the landscape as far as the eye could see. They had been there all along, but until I had seen the first I’d been oblivious to their presence, blind to their broadcast beauty.

I lay the book aside, realized my eyes no longer ached that much and neither did my heart. For the first time in several days, I got up from the couch and began to look around. Out the window, in the park, was a boy flinging a Frisbee, his dog springing like a pogo to catch it in its teeth. On the front porch up against the door was a fragrant crate of oranges with a get-well note from a friend. And in my computer inbox were some emails that had come in during the week:

From a student who’d just finished my writing course:

I have loved taking the writing class with you this quarter. I loved seeing your smile every Tuesday and Thursday 🙂 I feel like I have grown a lot as a writer because of your class.

From a student I’d taught in high school:

I just completed my first script and turned it in! What a rush! Thank you for inspiring me all the way to graduate school!

From the head of the English department at the college where I teach:

I just wanted to let you know that, if you’d like to teach writing next quarter, there’s an afternoon slot that’s opened up. And I want to let you know right now that I will have 1-2 writing sections per quarter next year available, if you’d be interested in signing up for teaching then too.

A leaping dog, sweet oranges, encouraging emails. This trio of brilliant cactus blossoms had been within my field of peripheral vision, but I’d let my umbrage at life’s prickles completely blind me to them. Now my eyes were open. And I knew that if I kept on looking, I’d find still more flowers on the trail.

Jan Vallone is the author of Pieces of Someday, a memoir, which won the 2011 Reader Views Reviewers Choice Award. Her stories have appeared in The Seattle Times, Catholic Digest, Guideposts Magazine, English Journal, Chicken Soup for the Soul, Writing it Real, and Curriculum in Context. Once a lawyer at a large law firm, and later an English teacher at a tiny yeshiva high school, she now teaches writing and literature at Seattle Pacific University.