On Wednesday, June 12, 2013, at more or less the same time that I was standing in a Greek Orthodox cathedral for the memorial prayers honoring the second anniversary of my mother’s passing, the Funeral Mass for David “Deacon” Patenotte was about to take place at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in my hometown of Yazoo City, Mississippi.

On Wednesday, June 12, 2013, at more or less the same time that I was standing in a Greek Orthodox cathedral for the memorial prayers honoring the second anniversary of my mother’s passing, the Funeral Mass for David “Deacon” Patenotte was about to take place at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in my hometown of Yazoo City, Mississippi.

I am a longtime Mississippi exile by this point, but I would have given anything to be in both places at once. As Father Steve censed the icon of Christ and asked for my mother’s memory to be eternal, I lifted up Mr. Patenotte’s name, too.

David, or “Deacon,” as he was known by most folks, was the owner of Patenotte’s Grocery on Grand Avenue: the expansive, tree-lined street that led out from the nineteenth century downtown to houses that were gradually newer, and finally to the flat streets of small 1950s and 60s houses that had been carved out of what had originally been the Curran family’s plantation.

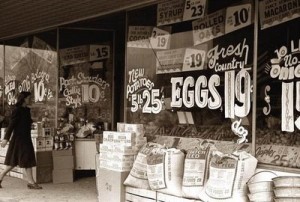

The original Patenotte’s had been a country store back when Grand Avenue ended in gravel, but by the time I was a child, a new, modern store with plate-glass windows and sky-blue iron siding was already several years old.

The store was a mere one block from my house around the corner, and various members of my large family would run over there multiple times a day, to pickup some item needed item, and Mr. Patenotte let us pay on credit. I was also allowed to go to Patenotte’s by myself when I was around four years old, an age that sounds insanely young for me to be crossing streets and going around corners.

But go I did, a dime and nickel in hand to buy a Three Musketeers bar, which cost thirteen cents.

One time, in one of my most frightening memories of early childhood (I must have been about two), I dropped a glass jar of Ovaltine and watched it explode on the linoleum into a cloud of chocolate and broken glass. I also remember, more than once, curling up to hide on the stack of twenty-five pouds bags of flour, clad in flowered cotton, that were on the bottom of the shelf of the baking aisle.

Given that Patenotte’s effectively functioned as an extension of our pantry, I had a front-row seat for the quotidian dramas that played out in its aisles. Mr. Patenotte was both owner and patriarch, and his voluminous energy and will permeated the store like a palpable force.

The windows were taped from top to bottom with his own hand-lettered sale notices, created from butcher paper scrawled with purple magic marker whose pungent ink was identical to the mimeograph machines in school: Try Some! Marked down now! And next to a basket of odd or dented items, Reduced for Quick Sale!

His office was perched in a little glassed-in cube up a few stairs from the store floor, and from which he could peer out over the store entrance and the two checkout lanes. More than once, I witnessed him ream out an employee—loudly, publicly, in a way that might be lawsuit-worthy today (a “tough love boss,” as his daughter Lillie noted on Facebook in announcing his funeral).

In this small supermarket his employees were like an ensemble cast: Pugh with his white paper hat and jacket back in the icy meat room, Caesar Felton who later became the Yazoo City sheriff, Ruth Brown whom I still go by to see at the Essco drugstore when I happen to be back home.

These employees I’m mentioning are all African-Americans, although he had many white employees as well. For part of the story of Mr. Patenotte is his courage during the Civil Rights movement: In the years of agony that preceded the final integration of the town’s public schools in 1970, Mr. Patenotte stood on the side of progress, inspired by the social justice teachings of his Catholic faith in a state that is still only 2% Catholic.

He joined the local NAACP, and thus avoided the local integration boycott by the black community, only to be accused by whites of being in it to make off with business for himself. My siblings had neighborhood friends whose parents forbade them to go to Patenotte’s on account of Mr. Patenotte’s politics.

“It was the first time I had witnessed that kind of explicit racism up close,” one of my brothers says.

Google Deacon Patenotte when you have a moment, and you can read the poignant, yet modest profile of him in Willie Morris’ Yazoo: Integration in a Deep Southern Town. This legacy should not be forgotten.

At the same time, the story of Mr. Patenotte is exactly opposite the kind of story we have come to tell about courage under these kinds of circumstances. He did not leap onto any kind of national stage; he did not try to capitalize on his simple efforts to live his values.

What he did do was keep running the store. He worked harder than any staff member he hired, from around six o’clock in the morning until long after dark. He worked in that store long enough to witness personal tragedy, from the death of his oldest daughter to the brain injury of his fourth daughter and death of his wife in a car accident.

He ran the store during the decades when the Yazoo Public Schools almost completely re-segregated, and later when the crack epidemic hit.

All along, it remained just that one well-run store, linoleum floors always smelling of Pine-Sol. There was no expectation that Patenotte’s grocery was something that needed to be marketed, or “brought to scale.”

He was faithful in a small thing. The name “Patenotte,” I am pretty sure, is a French diminutive of the Latin paternoster, in other words, the Our Father. I smile to myself thinking, what a providential and telling coincidence.

A native of Yazoo City, Mississippi, Caroline Langston is a convert to the Eastern Orthodox Church. She is a widely published writer and essayist, a winner of the Pushcart Prize, and a commentator for NPR’s “All Things Considered.”