With less than two days before the retreat began, and only a grain of time unclaimed by other responsibilities, I opened the Etz Hayim to Parashat Hukat and began to read.

With less than two days before the retreat began, and only a grain of time unclaimed by other responsibilities, I opened the Etz Hayim to Parashat Hukat and began to read.

I’d been asked to lead an aliyah, a calling forth of worshippers to chant blessings before and after the reading of a portion of the Torah.

Rabbi Jeff Roth, my friend and teacher and leader of the four night silent meditation retreat, had asked me to prepare a teaching based on a few verses of my choosing from Hukat (the name of that week’s Torah portion, hukat means “ritual law”). Those worshippers drawn by the theme of my teaching, which offered before the chanting of the Torah, would be invited up for a group aliyah.

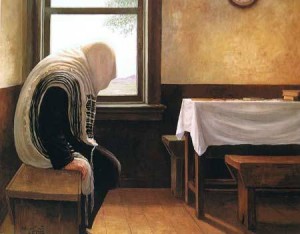

The blessing before the reading: an opportunity to gather one’s attention, inviting heart, ear, and mind to open to receive Torah’s wisdom. The blessing after the reading: an opportunity to experience the resonance of the Torah reading. Blessings before and after, and attending to the Torah reading itself: mindfulness practices.

While the discipline of my daily mindfulness practice (morning meditation, reading of the daily psalm) was unflagging as I headed into this retreat, my prayer practice, communally and in private, and my study of Torah had been at best infrequent for many months. No wonder, then, that my dedication if not devotion to other work—writing for “Good Letters,” reading illuminating poetry and prose, attending to important personal and family matters such as completing a will and an advanced medical directive—took precedence over preparing a teaching on a verse or two from Parashat Hukat.

Finally, fearing humiliation, were I to stand before the other retreat participants and offer a superficial teaching, I forced myself to lift the heavy book, turn to Numbers 19:1, and begin to read: “The Lord spoke to Moses and Aaron, saying: This is the ritual that the Lord has commanded: Instruct the Israelite people to bring you a red cow without blemish, in which there is no defect and on which no yoke has been laid.”

Reluctant to give myself—intellectually, imaginatively, spiritually—to the text, I willed myself to continue reading, desperate to stumble across a passage—a verse, a phrase—that would narrow the distance between Torah and me, that would save me.

“You shall give it to Eleazar the priest. It shall be taken outside the camp and slaughtered in his presence. Eleazar the priest shall take some of its blood with his finger and sprinkle it seven times toward the front of the Tent of Meeting.”

Still nothing. Still a hundred more tasks on my to-do list. A list that stood between me and Torah.

I needed a way in, and I needed it right away. The retreat would begin on Wednesday. That meant that I would still have a few days until Shabbat to prepare. But because reading and writing are discouraged on this kind of retreat, I didn’t want to miss the opportunity to give myself fully to the work of the retreat itself: extended periods of walking and sitting meditation, daily chanting of heart-opening lines from Hebrew prayers.

Merely a few verses into Hukat, a portion that runs from Numbers 19:1 to 22:1, I felt defeated. And I was experiencing anticipatory resentment at what seemed to me the inevitability of my having to “take time out” of the retreat to study the portion and prepare my teaching.

“The cow shall be burned in his sight—its hide, flesh, and blood shall be burned, its dung included—and the priest shall take cedar wood, hyssop, and crimson stuff, and throw them into the fire consuming the cow.”

In his sight: that phrase did it. My disinterest vanished. My detachment instantly dissipated. I had found my verses, Numbers 19: 5 – 6, or, more accurately, the verses had found me. Now I was awake and present. And I could see: from cow to hide, flesh, blood, and dung, the Torah zoomed in as if to make sure, make sure that…. Well, the next insight would arise only later.

Now I could turn to some rabbinic commentary. To have done so before, I felt, would have been cheating.

The opening verses in Parashat Hukkat describe what the commentators in Etz Hayim call “the strange ritual of the brown (‘red’) cow.” This ritual, they say, is “the classic example of a law that defies rational explanation.” “Yet,” they write, “there have been persistent efforts to uncover the lessons taught to us by this ritual.”

“Defies rational explanation”; “persistent efforts to uncover the lessons.” Of course! It’s not just a rabbinic response, a Jewish response to what appears to defy reason. This, too, might be worth highlighting: the way rabbis and the rest of us react when encountering the unknown, when reaching the limit of what we know and can know.

But where, in my own experience, can I find examples of how I respond to the unknown or uncertain? Without specific examples from my own life, my teaching would be merely a disembodied idea.

Tomorrow I witness the burning of the cow!

Richard Chess is the author of three books of poetry, Tekiah, Chair in the Desert, and Third Temple. His poems have appeared in a number of anthologies, including Bearing the Mystery: 20 Years of Image, Telling and Remembering: A Century of American Jewish Poetry, and Best Spiritual Writing 2005. He is the Roy Carroll Professor of Arts & Sciences at UNC Asheville. He directs UNC Asheville’s Center for Jewish Studies.