Guest Post

Continued from yesterday.

An increasing torrent of books and articles reflect on the Internet as The Great Distraction, and I’ve had the opportunity recently to read a few. The first I’ll mention is The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future, by Mark Bauerlein.

Bauerlein is not saying that millennials—youth who’ve grown up in the Digital Age—are less intelligent than their predecessors. He is saying that due to the digital environment in which they live and move and have their being, they are working with a much smaller store of acquired knowledge, contrasting the dizzying quantity of information available online with that which has actually been embraced and mastered.

Bauerlein collaborated with former chair of the National Endowment for the Arts Dana Gioia on the influential NEA reports Reading at Risk and To Read or Not To Read: A Question of National Consequence, which combined careful research and a sense of urgency about the rapid decline of reading in all age groups in the United States.

The omnipresence of screens and immersion in texting and social media have steadily pushed aside time devoted to reading or attendance to serious music, theater, and fine art. Bauerlein warns:

Every hour on MySpace, then, means an hour not practicing a musical instrument or learning a foreign language or watching C-SPAN. Every cell-phone call interrupts a chapter of Harry Potter or a look at the local paper. These are mind-maturing activities, and they don’t have to involve Great Books and Big Ideas. They have only to cultivate habits of analysis and reflection, and implant knowledge of the world beyond.

As the researcher behind the Reading at Risk report, Bauerlein has the expertise to marshal study after survey after anecdote to back up his vision of the increasingly desiccated nature of youth literacy and general historical and cultural awareness. He sees it as a threat not only to the quality and workplace preparedness of graduates, but to the vitality and coherence of our communities and of democracy itself.

Whereas Bauerlein’s book focuses mostly on the young, a book published this past summer strikes different notes, no less alarming. Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, is an extension of the author’s famous (or notorious) article in The Atlantic, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” published in 2008.

Carr, a media and technology analyst, began to worry when after “over a decade spending a lot of time online, searching and surfing” he had trouble reading a book or a substantive article. Carr explains, “Once I was a scuba diver in the sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.”

Carr’s case against those who would seek to relativize the media of our reading becomes most passionate in his chapter, “The Church of Google.” In it we are told of Google’s self-described mission, “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” which, we are told, will take about 300 years.

Google’s “Moon shot,” as one of its chief executives put it, is the Google Book Search—the effort to scan and digitize all the books ever printed and make them “discoverable and searchable online.”

The results frighten Carr, who warns, “The inevitability of turning the pages of books into online images should not prevent us from considering the side-effects. To make a book discoverable and searchable online is also to dismember it. The cohesion of its text, the linearity of its argument or narrative as it flows through scores of pages, is sacrificed.”

I ask myself why I find all this deeply saddening. Is it because I sell printed books and selling E-books holds no appeal? Is it because E-books threaten my livelihood?

I think I can honestly answer “no” (there are lots more immediate threats). I also reject what might be called the aesthetic objection to the electronic book (which I think can easily descend into sentimentality)—you know, acclaiming the beauty of physical books as objects, the way they smell, the way they feel, etc.

No, there is a more profound objection or resistance to the E-book, which, for lack of a better label, I’ll call theological.

I’ll just say it: E-books are a gnostic technology that nourishes gnostic tendencies. And I’ve been taught, and know historically, that gnosticism is heresy number one.

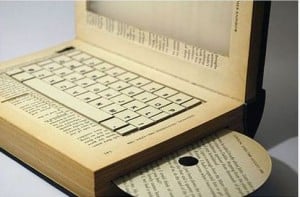

When we read physical books, the text is physically mediated in a delightful, infinite variety of ways. The word comes incarnate in ink and paper and covers. The word in E-books, I know, is also physically mediated, but it tends toward the virtual, and renders the medium immaterial.

Just as the Docetist variety of early Christian gnosticism taught that Christ only seemed to be human, so E-books lend a ghostly air to the screen presence of whatever text it displays.

I began by relating the deeply formative reading experiences books rendered, saying “the object and the experience they mediated are inseparable.” I can’t imagine saying the same about any electronic reading experience.

Yes, the electronic text is “there”—but just barely. There’s not very much “there” there. The incarnate element involved in reading has nearly disappeared, and our nature as composite beings of flesh and spirit—this nature for which Christ took flesh—is left strangely starved. Our physical natures, yearning for incarnate spiritual experience, are considered irrelevant.

There is no longer a sense of journey or pilgrimage through a story, as anyone who’s read a long text with delight or arduous sweat knows. The E-text floats in a boundless sea of nearly identical pages, and any sense of beginning, middle, and end has fled away. In a physical book, the text has particularity, to which we can relate even spatially.

How many times have you been looking for a sentence or a passage, and said something like “it’s on the right-hand page, about three lines from the top,” this memory immediate and precious to you?

The proponent of the digital book might run an electronic search of his text and immediately locate the sought passage—but is there a real sense of where it is in relation to the rest of the book? The book itself is marked by our journey through it—yellow highlighter here, coffee stain there, spaghetti sauce spattered on page forty-five. We yearn for physicality—it’s our created nature—and books satisfy.

We mark them, they mark us. It’s an intricate, beautiful physical/spiritual dance.

The object and the experience they mediate are inseparable. I might just as well have said that good books—good words incarnate—are sacramental.

Warren Farha is a lifelong, contented resident of Wichita, Kansas, son of a Lebanese immigrant’s son and a Kansas farm girl. He grew up in his father’s business, until a pivotal moment in 1987 led him into a new vocation of bookstore owner. The bookstore in mind was interdisciplinary featuring classic, perennially important books in literature, theology, history, the arts, and children’s literature, one that also brought his native Orthodox faith into wider contemporary intellectual and cultural conversations. Eighth Day Books is now almost twenty-five years old. Warren shares this endeavor with his beloved wife Chris, three grown children, and a host of past and present friends.