In the months to come, England’s National Health Service will sterilize a young man with a very low IQ. In Philadelphia, a three-year-old who will soon die without a new kidney is barred from entering the organ transplant waiting list because she is mentally disabled. I suspect most of us have lost the moral language necessary to talk about either. We don’t know how to discuss these facts any more than we know how to discuss God or the soul or beauty or art, and if you want to understand the slow dissolution of human communities you can begin with the disintegration of moral imagination, and with it a language for good and evil.

In the months to come, England’s National Health Service will sterilize a young man with a very low IQ. In Philadelphia, a three-year-old who will soon die without a new kidney is barred from entering the organ transplant waiting list because she is mentally disabled. I suspect most of us have lost the moral language necessary to talk about either. We don’t know how to discuss these facts any more than we know how to discuss God or the soul or beauty or art, and if you want to understand the slow dissolution of human communities you can begin with the disintegration of moral imagination, and with it a language for good and evil.

Our lack of moral language should not be mistaken for lack of moralizing. In fact, the opposite relationship holds true—our rhetoric about what is moral yearly escalates because volume triumphs where authority has gone missing. Likewise for our words about God; heresies large and small proliferate in near-exact proportion to the growth in blogs opining about what God thinks about what we imagine he must be thinking about, which almost certainly must be the things most important to those of us who have blogs.

Everyone is too busy composing his memoirs, meanwhile, for there to be much conversation about what is art, other than to say that surely it is that which I like.

So how to talk about the apparent return to a shameful practice—not confined to Britain’s shores—of sterilizing the mentally unfit? How to talk about counting a retarded girl’s life as less valuable? Perhaps I’m being overly squeamish; in the first case, the head of an organization claiming to represent the interests of Britain’s mentally handicapped could be found on the television, praising the wisdom of the court’s decision.

After very careful deliberation, we are assured, the judge sided with social workers, who agree that sterilization is in the young man’s best interest. He’s already sired one child with his girlfriend, who also has a low IQ. His parents insist that he will be profoundly unhappy if he has more children. Presumably they and the social workers will be unhappy as well, having to care for more potentially handicapped babies—children like Amelia Rivera, the three-year-old slated to die in Philadelphia. And what of overworked taxpayers, who must underwrite these feeble lives? Surely their interests should be considered as well.

It is all very efficient and tidy and humane. One will receive a mild sedative and some painkillers. The other will be helped into gentle sleep when her time comes. We’ll forget them soon enough.

It happens too easily. Everyone agrees, for example, that the British man should be sterilized. Every news article about the case points out that everyone agrees. Why does everyone need to keep reassuring us that everyone agrees? I honestly don’t know what should be done in either case, but I am certain that the realm where good and right choices may lie extends beyond economics and utility, and hence beyond our capacity, any more, to fully discern them.

The language of materialism has been prevalent on the political Left all the way back to Marx, and with the triumph of corporate-centered economics over other community concerns, utility now dominates the language of the Right. From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs, what’s good for General Motors is good for America. Our moral language has become a language of utilitarian materialism, of incremental increases in human happiness.

And what is our moral landscape, from this vantage point atop our slide into the twenty-first century?

Universities justify their existence with their contribution to the gross domestic product.

Churches promise happiness, order, a beneficial life.

We renew a queuing of the mentally infirm to the bottom, albeit gently this time.

We chatter about the psychological and sociological and political origins of school shootings and soldier suicides and the sexual deviancy of congressmen, our words neglecting a quiet truth that has no place in the conversation of the twenty-first-century West—because it is not a fact that can be measured like the weight of a carbon molecule or the earnings of Ford Motor Company—namely, that we are sick in our very souls, were sickened soon after we began, and will only grow sicker so long as we entertain the fantasy that we are each of us no more than watches that must be occasionally adjusted.

“The traditions,” wrote Viktor Frankl in 1962, “which buttressed [man’s] behavior are now rapidly diminishing.” We are falling, Frankl contended, into an “existential vacuum.” Absent traditions to guide behavior, man “either wishes to do what other people do or he does what other people wish him to do.” Man loses, in this vacuum, his sense of worthwhileness. Little wonder that he loses his sense of others’ worth as well.

We have no moral language, then, because we have allowed the measure of things to be reduced to their quantifiable purpose, and the measure of us to be no more than the sum of our finely parsed parts. As a consequence, we have no way to judge good from evil, save by comparing the cost to our wallets of each.

To be continued tomorrow.

Tony Woodlief lives outside Wichita, Kansas, and is the author of a spiritual memoir, Somewhere More Holy. His essays on faith and parenting have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The London Times, and WORLD Magazine. His short stories, two of which have been nominated for Pushcart prizes, have been published in Image and Ruminate. His website is www.tonywoodlief.com.

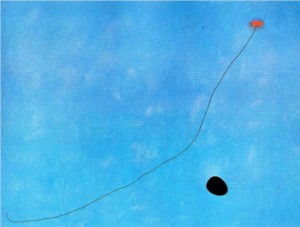

Art above: Joan Miro, Blue III, 1961.