Not too long ago, just as spring was turning over into summer, I awoke with a slight numbness in the fingers of my right hand. The morning was early yet, the sky outside still dark, and as I wrote, my fingers were a little slower than usual to find their keys. By the end of the day, I was fumbling in the most ordinary of tasks, like opening a jar of peanut butter or reaching for a doorknob.

The next morning, I dropped my toothbrush; days later, I could no longer sign my name, which struck me as somewhat scandalous. I could not brush my hair (a secret vanity of mine), or unbutton my husband’s shirt (a secret pleasure of an altogether different kind).

Before the end of the week, I found myself in the radiology unit of our local hospital. As the technician pushed me into the MRI machine, I thought of medieval monks with their halos of hair and the coffins they climbed into each night to sleep.

Time is an altogether other force in the tube—it operates by a different set of rules—but inside, holding myself stiller than still as each scan sounded its blaring alarm, I did not worry so much as wonder at this swift betrayal of my body. Even then, in those early days, my body did not seem unkind to me.

By the time the diagnosis was confirmed, nearly two weeks after the onset of my first symptoms, it seemed oddly anti-climactic, almost beside the point. Time passes and time does not pass. And so already, even then, when I heard the words multiple sclerosis, what interested me most was not the disease so much as the disability, because if my hand failed me once, falling away from me like so many strings of a marionette, it could fail me again, and how could I write if I could not feel the keys beneath my fingertips, hear the rhythm of my words as they made their first noisy appearance in my early-morning world?

At first, I thought I might keep it a secret, this new disease, because privacy is a long-lost treasure in this world. I was eager to set something apart, to call something mine and mine alone. It made me feel powerful, toting around this secret knowledge, harboring this (mostly) invisible disease in a body that is, if you are the kind to trust appearances, young and healthy and able.

So I made a private resolution to tell no one. But, of course, it did not last. It turned out to be a perverse and misguided effort, far too exhausting to maintain. Secret ills, after all, are quite different than secret pleasures.

So here I am, much to my own chagrin, writing about it, not because I want to (I do not, in fact), nor because I feel the need to “come out” with it or to “identify” with it or even to “process” it—no, nothing so noble as any of that. I am writing about it simply because it happens to be in my way, this disease.

Before my diagnosis, I woke up at five to write for two hours before heading to my day job. I sacrificed sleep, exercise, and, on more than one occasion, meals, so that I could tap out my fanciful stories on this ancient laptop of mine.

Sometimes, as the saying goes, there is no way out except to go through, so here I am, doing it the only way I know how to do anything, which is to write my way through it, trying to navigate the gnarled, foreign landscape that my body has become, with words as my unsteady compass.

There is a whole trove of literature about sickness, I know—a rich tradition of “illness memoirs”; by writers who are also doctors, scribbling story ideas on prescription pads in between appointments with patients who may also be writers themselves, like me.

But to be honest I am not all that interested in reading about the experience I now find myself to be living. I am too restless; I do not have the patience for it. Once is enough (and too much, at that).

What interests me, rather, is how to be in this new body of mine that seems to demand so much more time and attention and, yes, feeling, than ever before. When I most want to escape my body, with its sudden, myriad betrayals and petty idiosyncrasies, how might I manage to burrow still deeper into myself, to take up refuge in this body of mine that has disappointed me so, and therein find the monk’s cell where I can write?

After earning her Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing at the University of Washington, Paige Eve Chant was awarded the 2010-2011 Milton Center Postgraduate Fellowship. She is currently at work on her first novel. Read more of her work online at www.paigeevechant.com.

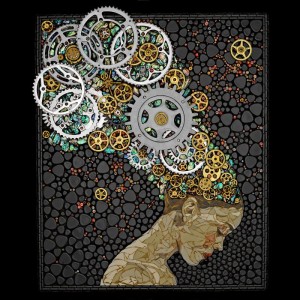

Art Pictured: Laura Harris. Ashima-Endless, Limitless, without boundaries.