“There is no death, only a changing of worlds.” —Chief Seattle

“There is no death, only a changing of worlds.” —Chief Seattle

At night I lie in bed and think of the cemetery gate on Monument Hill. It was a fairly steep climb up a gravel path and always left me winded, so I didn’t often attempt it with our all-terrain stroller. At the summit is a clear view of the college grounds and a circular, enclosed graveyard where the founders’ bodies lie.

I will likely never open that gate again. I wonder how long my arms will hold the recent memory of tugging at the rusted iron, the screeching of metal on the stone steps so loud it set my teeth on edge. I brace myself against the sound and pull.

I turn over in bed and rearrange the covers, hear the wind in the pines. The weather is already so cool in Northern Michigan, as cool as I remember my last winter in Virginia, and it’s only September. I’m restless at night. I reach for the gate. The grating of metal resounds in the earth and in my stomach. The kids cry out and cover their ears.

Inside the stone enclosure, the grass is lush and soft. The kids dance on the graves. The columbarium is their stage. They never want to leave, but I anticipate the long walk home. There are tears.

I’m romanticizing. I do that. It’s how I’ve always managed; I tell myself stories, create tableaux.

For six years in rural Virginia, at home with small children, I lived in what seemed a world of my own creation. There were many hours to fill and few people to see. There were horses. There were two trees at the stable gates, the sentinels, who watched us sidelong as we came and went.

Were they maples? I wonder in the night. I realize I never thought to identify them, or even look at them very closely. They were like something out of Tolkien and seemed as if they might speak at any moment. Avoid their gaze! I’d warn, and we’d try to pass between them without a sound.

For six years I walked the Dairy Road, first with one child and then with two. We carried walking sticks made from fallen poplar branches in our yard. Unpacking boxes in Michigan, I pause and close my eyes and feel their rough wood in my hands, the gravel under our feet, a pebble stuck in the arch of my sandal. I smell the rank, wet smell of the old dairy and hear the nickering of horses.

We packed up six years in a week, six years taped and labeled or sold in the driveway. We sold so much we no longer need—infant clothes, diaper covers, the sling, the play-mat, the high chair, the blue plastic tree swing both children have outgrown.

We left for good reasons, the reasons anybody leaves any place: better jobs, more opportunities. I repeat the reasons as I rearrange the sheets, switch the pillow to the cool side.

But my thoughts keep returning to what we left behind: their babyhood, my young motherhood, the long hours of isolation, the endless retelling of tales, the cooing of the ladies in the bookstore and dining hall, the rainy winter days when I thought I’d die of boredom and loneliness but for their sweaty heads on my aching arm as they napped. I’m waking from dreams of who they might be, who I might be, into a world beyond my control.

In time, I will forget the feel and sound of the rusty gate. I may be a romantic but I benefit, as Flannery O’Connor once said, from a lack of retention. For now, I keep the framed baby pictures in a box in the basement. I’m reading up on Michigan lore. I’ve learned the sandy soil has a name, kalkaska. I told Alex about Paul Bunyan. Last weekend we went to Rainbow Bend National Forest, where the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians were releasing baby sturgeon into the Manistee River.

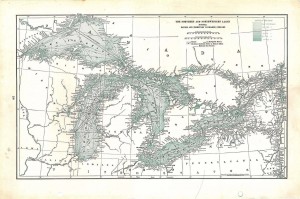

Charlotte listened as the chief told of long-gone days of virgin forests and lakes, of a prehistoric fish that could grow to be eight feet tall and three hundred pounds and one hundred years old. He quoted Chief Seattle, though I’m not sure why, because I stopped listening after he said it: There is no death, only a changing of worlds.

The drums beat as we walked with the children down to the riverbank, each holding a young sturgeon ready to be returned to the Great Lakes. Water sloshed dangerously over the sides of their tin pails. “So I’ll be 107 when this sturgeon dies,” Charlotte said, and I paused just a moment before I answered, “Yes, you will.” I reached out to steady her on the slippery rocks, checked to see that Dave was helping Alex. They knelt and tipped their buckets.