A few years back, I watched an interview with a middle-aged woman who was educated, attractive, and well-spoken. She was also in jail—had been for thirty years and would be until the day she died. In her youth, as part of a drugged-out cult, she’d stabbed a young mother to death, slit her husband’s throat, and helped chase down and eviscerate a pregnant girl. She was penitent in the interview, but admitted that she was not particularly remorseful during her trial or for a long time thereafter.

A few years back, I watched an interview with a middle-aged woman who was educated, attractive, and well-spoken. She was also in jail—had been for thirty years and would be until the day she died. In her youth, as part of a drugged-out cult, she’d stabbed a young mother to death, slit her husband’s throat, and helped chase down and eviscerate a pregnant girl. She was penitent in the interview, but admitted that she was not particularly remorseful during her trial or for a long time thereafter.

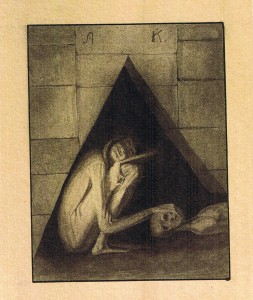

The most chilling thing she said was in response to the reporter’s comment that he would never have thought her capable of such a thing. The inmate replied: “I would never have thought that either; I sometimes have a hard time thinking it now; but I was; I am.”

Why that reverberated so strongly with me was because I have often wondered what all I’m capable of—for both good and ill; I’m much more humble about that than I used to be.

When pressed too far, when down too low, when too far along a ruinous path—whether led astray by others or of our own volition—who knows what we might do. So best to hold tightly to that which orders the appetites; best to make virtue a habit, as Aquinas counseled.

By the same token, but at a greater level of abstraction, when discussing current affairs I’ve recently heard boasts along the following lines: “Yes, but that kind of thing could never happen here.” It will be said in reference to some late atrocity in a foreign land, and supported by arguments resting in our common history, secular institutions, and set of basic human virtues. These things will insulate us from the fate of the less enlightened parts of the globe, it’s suggested.

Needless to say, I’m not so sure. Since I’m dubious about my own motives much of the time, or of where they might lead me, a fortiori, how much more dubious am I about those of authorities who swear up and down that they “know what’s best.”

One of the things I’m reassured “could never happen here” involves the Romeike family, evangelical Christians from Germany. They fled to America in 2008 because their home country still enforces a 1918 law that outlaws homeschooling.

The parents faced felonious penalties there because they wanted to determine for themselves the kinds of things their children should learn. This, the judges said, amounted to neglect. If the Romeikes didn’t comply—well, you know what happens to the children of parents who “neglect” them.

“They wouldn’t do anything like that,” I’ve been told. “Don’t be an alarmist. Besides, they simply could have moved if they didn’t like the law; they brought this on themselves.”

Well, witness the Wunderlich family, who weren’t as quick to the German border as the Romeikes. Last fall, the state showed up at their home with a twenty member raid team, armed with battering rams; they then took the homeschooled children away in a terrifying assault and kept them for three weeks. The judge also approved force against the youths themselves, if during that time they resisted what was being done “for” them.

The Wunderlichs then complied with the state education of their children while they worked through the process of immigrating to France (which allows homeschooling). Amazingly, the court refused to give the parents legal custody; the reason: child endangerment. So not only must the parents submit to the state’s educational edicts, they are not allowed to quit the country; or rather, they may, but at the forfeit of their children.

That is why the Romeikes wanted to come here, to a place that would respect the fundamental prerogative of parents to decide their children’s educational interests; “that couldn’t happen in America,” they thought, not with its heritage of respecting both individual rights and religious conscience.

Except that it could. Despite the fact that asylum was initially granted, and that the Romeikes would face the same fate as the Wunderlichs if sent back to Germany, the present administration—which has been extremely open to various other immigration claims—has worked tirelessly to have their protections revoked. All that keeps the family from deportation now is a Supreme Court order that requires Attorney General Holder to answer the Romeike’s petition to be heard by January 21.

Nothing has suggested that these boys and girls are in any physical or psychological danger; the Wunderlich children were subjected to government testing and found to be well-adjusted and academically sound, even by state standards. The children belong to model, loving families.

The argument about basic human rights has been long, both as to the list of those rights and as to the fount from which they spring; to oversimplify the point, are they innate and inalienable, or are they created and granted only by the body politic? This is the natural rights school versus the positivist school.

One of the major sticking points regards the relationship between parents, children, and the state. Who has the prior right in that triad? Catholic social teaching has championed the preeminence of parental privilege in educating children (Gravissimum Educationis, Article 6) and secular institutions have recognized the same. According to the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights, compiled after WWII in response to Nazi atrocities, parents have the first say in how their children will be educated (Article 26 (3)). Our own jurisprudence agrees (Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 1925).

But none of this has held any sway, not in the Romeike’s old country, nor in their hoped for new one. Even homeschooling foes can be stunned at that.

We may never think we’re capable of certain things, or that we could let them come to such a pass; one day we may look back at the events and marvel that they ever happened. But to paraphrase that attractive, well-educated inmate—they did; they will yet; and we are.

A.G. Harmon teaches Shakespeare, Law and Literature, Jurisprudence, and Writing at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. His novel, A House All Stilled, won the 2001 Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel.