When someone dies, we say to the surviving family members, “I’m sorry for your loss.” And we mean it. But there are other ways than death to lose someone dear—or someone who should be dear.

When someone dies, we say to the surviving family members, “I’m sorry for your loss.” And we mean it. But there are other ways than death to lose someone dear—or someone who should be dear.

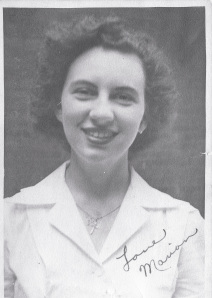

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell explores these varieties of loss in her latest poetry collection, Waking My Mother. The poems reflect on her mother’s dementia and dying; on her mother’s relation to Angela and her siblings when they were kids; on the emotional complexities of living, after her mother’s death, with memories of a mother she wasn’t loved by.

Yes, this is the tough stuff that O’Donnell takes on in these poems. And she takes it on with grace.

One of the hardest things to take on—perhaps the hardest to read about—is her memory of her mother’s succession of lovers after their father died.

Other girls’ mothers

sold Avon, Bee-line, Tupperware.

My mother took lovers.

Young ones. Dark ones. True ones.

The kind that came back,

parked their cars in the drive,

and slept in our house

night after night after night.

Or this, from the sonnet cycle that opens the book:

Laying claim to what we no longer possessed,

we each performed her offices of love,

while our mother grew more distant and obsessed,

we spent our days and nights trying to prove

we could cure her selfishness by giving.

We learned to live, as people do, by living.

Our mother fell in love with scotch and men.

She kept the bottle on the kitchen counter.

She brought men home with her to be her lovers.

She got so lost in them we never found her.

For me, that last line shrieks with pain. The kids lose their mother’s love because she is lost in her lovers. Isn’t this a type of child abuse? Yet O’Donnell won’t call it that, and she controls the pain within the sonnet form.

These poems are searching rather than cynical. What they keep searching for is a way to honor her mother’s life. A way to “wake my mother” (as the book’s title puts it)—wake her into a truer motherhood.

And so, in the opening sonnet, O’Donnell is at the bedside of her dying mother, making the sign of the cross on her mother’s forehead. And recalling her own choice in adulthood to place her own children above her care for her mother:

that I have made a choice that means the loss

I claimed so long ago is mine forever,

all sealed by this Distant Daughter’s cross.

Rhyming “loss” with “cross.” I sense that all the emotional complexities of this volume are captured in that simple rhyme.

For all our losses are crosses, aren’t they? The loss of love, of hope, of health, of dignity, of a life. We say of someone dear “he lost his job”—and all the pain emanating from that loss is surely his cross. I say of a period of my life “I lost my bearings”—and the cross of psychic breakdown reverberates in the phrase. The bank forecloses and my friend “loses her house”: the words look as simple as “she lost her gloves” or “she lost her car keys,” but what a cross in that loss of a home. Yet another typhoon strikes the Philippines, and people “lose everything.”

O’Donnell is exploring varieties of loss. But her book is also a lost and found. Poetry can find something in our losses. The creative act itself, Elie Wiesel once said, is a gesture against despair.

Here is “Losing My Mother”:

I’ve lost my mother,

careless daughter,

mislaid her,

left her behind.

I’ve let them take her

to a place I cannot find…

I’ve lost my mother.

Like a sheep,

but number one,

not ninety-nine.

Like a coin.

But the most valuable and fine.

Like the pearl I owned

but is no more mine.

Like my mind.

The poet has “lost her mind.” And yet of course she hasn’t—not when she can create a sharp, crisp poem like this one. In the poem, she “finds” at least as much as she has lost: she finds just the right rhymes to tie all together, just the right gospel parables to expand the poem’s referent way beyond personal loss. She finds, in these parables, the kingdom of God.

If loss is a cross, then finding is the resurrection. What’s found in the creative crafting of poems is a new sort of life.

Peggy Rosenthal is director of Poetry Retreats and writes widely on poetry as a spiritual resource. Her books include Praying through Poetry: Hope for Violent Times (Franciscan Media), and The Poets’ Jesus (Oxford). See Amazon for full list. She also teaches an online course, “Poetry as a Spiritual Practice,” through Image’s Glen Online program.