Sunday at the Oscars, Spike Jonze deservedly won Best Original Screenplay for Her, his dystopian love story for the cybernetic age. In an alternative world, the kind that Jonze likes us to inhabit in his films—strange but relatable, infinitely ironic—I’m pretty sure that he also took home the award for Best Parable.

Sunday at the Oscars, Spike Jonze deservedly won Best Original Screenplay for Her, his dystopian love story for the cybernetic age. In an alternative world, the kind that Jonze likes us to inhabit in his films—strange but relatable, infinitely ironic—I’m pretty sure that he also took home the award for Best Parable.

Or, in keeping with Jonze’s boyish persona that seems to shrug at his own brilliance, perhaps it was Best Parable In Spite of Itself.

Why in spite of itself? Because while Jonze obviously set out to write a screenplay, and then direct a film, I suspect that he did not task himself with the conscious making of a cinematic parable in the same gospel vein employed by Jesus of Nazareth.

But he did, and to no unimpressive end. (Not surprisingly, after all, this being the director whose precocious dexterity in his early films like Being John Malkovich and Adaptation felt like effortless deliveries of gemstones on a skateboard.)

Just put on your inner Jonze and imagine that Jesus hailed from Nazareth, Pennsylvania in our day and age. You can almost hear him begin the parable of Her to a street crowd in Philadelphia, many of whom must remove their earbuds and headphones to listen:

“There was a man who fell in love with an operating system…”

If you’ve seen the movie, you know how the parable goes from there and how it ends. And if you haven’t, I suggest that you do for its ultramodern example of this ancient literary form that many readers and believers might consider spiritually relevant but culturally outdated.

Parables? Weren’t those for farmers and fisherfolk? Yes, but no less so for Facebook Friends and social media buffs in the (dis)connected world—not to mention artists of faith who toe that precarious line between the medium and the message.

If Jonze has any message in Her, it likely has more to do with humanity’s relationship to technology than to God. Then how is it that in watching the film I experienced no less an application (pun intended) to the latter than the former?

Because by putting a premium on the medium—as any good artist like Jesus knows best to do—by telling a story that prizes poetry over platitude and detail over dogma, Jonze gives us a parable that, intentionally or not, operates (let the puns speak for themselves) on two planes at once just as Jesus’s parables did with their original audiences.

For if seed and harvest spoke of the Kingdom of God to the farmers of first-century Judea, do Wi-Fi (don’t let that one escape you), text messaging, and the disembodied phenomena of programs that know more and more about who we are and what we want, not have the same resonance for twenty-first century technophiles?

In fact, I would argue that our technological context is an exponentially more fertile field for such parabolic thinking, and invites a fascinating meditation on the inherent parallels between the Kingdom and cyberspace.

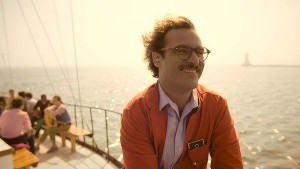

At least that’s what it felt like at times watching Peter (Joaquin Phoenix) engage with Samantha (the disembodied Scarlett Johannson) in Her. There he is, talking to an unseen entity as close as his own breath, available anywhere and everywhere at a moment’s notice.

And what begins with his one-sided need for company in the wake of a broken marriage leads to a reckoning that what he has signed up for with his virtual demigoddess is nothing short of a relationship that risks and requires intimacy of an otherworldly kind.

“As it is in the natural, so it is in the spiritual,” the wisdom goes, with various verses from scripture to make the point. Watching Peter traverse the terms of communication with Samantha, who is altogether present though unseen and intangible, the wireless corollary was all too apparent: “As it is in the technological, so it is in the spiritual.”

Or perhaps the formula should be flipped, given the portals of virtual reality we have only begun to enter: “As it is in the spiritual, so it is (and will be) in the technological.”

Of course a host of qualifications pertain to the comparisons that I’m drawing here, lest it sound like I’m suggesting in any facile way that Peter and Samantha’s relationship is an accurate picture of my or your relationship with God. If you’ve seen Her, you know there’s a whole side to their relationship that we do not undertake with God.

And it would take far more space than what is left here to parse out the differences and similarities between their digital communion and our divine one. For starters, I would have to ask who the actual god-figure is in their relationship, because Peter shares that role as much as Samantha does—which lends the ending an extra layer of heartbreak.

But it’s the conceit of the film apropos a fundamental concern with relationship between two beings of coexistent realms that makes it so germane to the question of faith. For it’s a very real relationship in Her, one that makes me consider how I can be far more programmatic at times in relating to God than Peter is to Samantha, or Samantha is to Peter.

In this way, the movie’s virtues as a parable shine. Because for all the healthy talk in church today of intimacy with Jesus and a personal relationship with your savior, it seems that corporately and individually we often default to a one-dimensional mode of spiritual nicety. Yet the Hebraic tradition prescribes a wondrously complex, and therefore complicated, intimacy of the kind that Abraham, Moses, and Jacob practiced—the kind that literally defines Israel as “strives with God.”

The kind that Peter and Samantha share in their striving to connect.

How easy it is to forget that in his parables Jesus made little or no use of religious diction. He told stories that spoke for themselves, of things beyond themselves.

He modeled an art form that twenty centuries later lets Her speak of Him.

Bradford Winters is a screenwriter/producer in television whose work has included such series as Oz, Kings, Boss, and The Americans. His poems have appeared in Sewanee Theological Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, and Georgetown Review, among other journals. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and three children.