I’ve been taking an antidepressant for six months now. Psychiatry wins: I’m a more functional human. I don’t feel so isolated and restless. The tasks of daily life don’t seem impossible. Even the feeling of shame that I need to be on medication has been lessened by the medication. But it’s a dry season, God seems distant, and some days I don’t recognize myself.

I’ve been taking an antidepressant for six months now. Psychiatry wins: I’m a more functional human. I don’t feel so isolated and restless. The tasks of daily life don’t seem impossible. Even the feeling of shame that I need to be on medication has been lessened by the medication. But it’s a dry season, God seems distant, and some days I don’t recognize myself.

I wonder how much higher the dosage would have to be to silence that little voice that wonders with every shift in mood and emotion—is this me or Celexa? Is the real me revealed when the medication suppresses my anxiety, or am I suffocating her with an SSRI? Is there a drug that can quell this stubborn refusal to be well—even though I feel well—the belief that peace is just a chemical haze that clears as soon as the bottle empties?

At the risk of sounding like a religious freak, or even just a garden-variety freak, I confess I’ve often worried that this voice inside is the devil. Except it’s the same voice that urges me to write and to throw myself at the foot at the cross—two good things I’m decidedly less inclined to do now that I’m on drugs. Physically, mentally, I’m waking up, getting well, returning to life. Why do I feel so spiritually and creatively dead?

As I wade out of this bout with depression, daily events seem less burdensome and full of portents, and my religious sense wavers and I question my theological scaffolding. What if my attraction to Christianity, and in particular Catholicism, is merely a symptom? For a brain hardwired to think the worst, it’s easy to accept the theology of the cross, to believe that life is pain, as heartbroken Westley says in The Princess Bride, and anyone who says differently is selling something.

For too long I’ve imagined a God who redeems suffering but is indifferent to happiness, at least in this life.

The Christian life isn’t about finding your bliss, it’s about taking up your cross. Suffering unites us with Christ, and the poor in spirit are blessed. That’s been my creed, and I’ve spilled much of my own ink writing against the current obsession with gratitude and mindfulness as the keys to the Christian life. “What people don’t realize is how much religion costs,” wrote Flannery O’Connor in one of her letters. “They think faith is a big electric blanket, when of course it is the cross.”

But medicated, the desire for happiness in this life doesn’t seem shallow and misguided; it seems healthy.

“Dead periods have not been rare in my life,” wrote the Catholic publisher and writer Maisie Ward. “For Gerard Manley Hopkins, Our Lady was like the air we breathe. But the lungs of most of us are filled with a mixture of psychology and physical science and the fumes of pleasure or pain of daily living…We examine our conscience, but our whole religious mind needs examining occasionally to check its contents against reality.” I find myself at such a turning point, a time to look outside myself and test the story I’ve been telling myself for what is true and what is the result of my lack of serotonin.

Meanwhile I’ve been watching the Cosmos reboot with my eight-year-old daughter, who is nursing a serious crush on Isaac Newton. I’d be irritated by the show’s obvious mission to disabuse religious people of their superstitions no matter what pill I was swallowing, but in this dry season I’ve watched through my fingers, half afraid that after all the real trauma I’ve experienced without losing my faith, it will be some insignificant twaddle about being made of stardust that will at last tip the scales in favor of unbelief.

And yet, despite itself, the show has opened my eyes to a very Christian idea: that being in relationship is essential to our progress toward the truth. In my daughter’s favorite episode, we learn in a charming animated segment that the friendship of Sir Edmond Halley was essential to the publication of Newton’s Principia Mathematica, the opening pages of modern science. The idea that friendship could have such a lasting impact on the world is as appealing to me as it is to my child.

Suffering and affliction do unite us with God, but they tend to remove us from others. Depression seals me in a chamber, makes relationship difficult if not impossible. Even the smallest challenges seem insurmountable: it seems clear nobody can help me, and the idea that I might be able to help anyone else is unfathomable. Depression prevents me from being in communion. And communion, for a Christian, is not optional.

I feel closest to God when I’m suffering—that’s truth. And I’m afraid that for me the cliché of the tortured artist is true—I’m much more prolific when I’m not on medication. But the challenge for me now is to see God and live out my vocation in health and yes, even happiness. When am I happiest? With my family, with my closest friends, and when I reach out to others, even strangers, in love.

Depression brought me close to God, but healthy, maybe I can bring God to someone else. A new season, yes, but maybe not dry after all.

Jessica Mesman Griffith is a widely published essayist and the author of the memoir Love & Salt: A Spiritual Friendship in Letters, winner of the 2014 Christopher Award. She lives in Northern Michigan with her husband, writer David Griffith, and their two children.

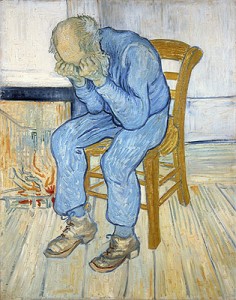

Image Used: Sorrowing Old Man (At Eternity’s Gate) (1890), by Vincent van Gogh, oil on canvas, 31.5 × 21.2 in.