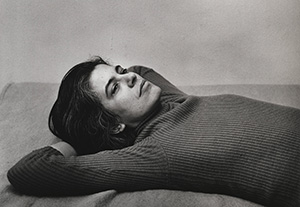

I could stare for many hours at that famous 1975 picture of Susan Sontag lying on her bed. She’s wearing a turtleneck sweater and her arms are tucked behind her head. She is thinking. Her eyes are open, slightly dreamy, but fixed.

I could stare for many hours at that famous 1975 picture of Susan Sontag lying on her bed. She’s wearing a turtleneck sweater and her arms are tucked behind her head. She is thinking. Her eyes are open, slightly dreamy, but fixed.

She looks serious. How else could she look? By God, that woman was serious. It is her main contribution as a belletrist, the idea that seriousness itself is a goal, that in the collapse of all other values, we can be serious about being serious.

There is also a picture of Simone Weil at age thirteen, before she got those round glasses you see in the later photos. Weil is laughing and pretty and resting her left arm casually on her neck. It seems impossible that this is the woman who later refused treatment for her tuberculosis and who more or less starved herself to death out of spiritual solidarity with those suffering under German occupation during WWII.

Susan Sontag wrote a review of a collection of Weil’s essays for the New York Review of Books in 1963. Sontag used the publication of Weil’s essays as an excuse to talk about her favorite subject: being serious. Sontag loved Weil’s harshness, her unrelenting, unremitting commitment to seeing her thoughts through wherever they lead.

No doubt, Weil was just as serious as Sontag thought her. Like all the great mystics, Weil wanted to reduce herself to the point of a point. She wanted to make herself small so that God could become bigger, could take over the negative space she was leaving behind. She was serious, in other words, about suffering.

But Sontag was uninterested in the content of Weil’s thinking, only the way she thought about it, the manner of her thinking.

It is almost funny how Sontag, who wanted to be large, tried to steal the seriousness of Weil for herself, throwing away the smallness that Weil wanted us to be serious about. Sontag wrote, “We read writers of such scathing originality for their personal authority, for the example of their seriousness, for their manifest willingness to sacrifice themselves for their truths, and—only piecemeal—for their ‘views.’”

Just pick something, anything, and be serious about it. That seems to be Sontag’s message. That’s good enough for her. Sontag seemed to think that seriousness itself can exist as a kind of hovering absolute, an end in itself.

Sontag wrote of Weil, “No one who loves life would wish to imitate her dedication to martyrdom nor would wish it for his children nor for anyone else whom he loves. Yet so far as we love seriousness, as well as life, we are moved by it, nourished by it.”

But why do we love Weil’s seriousness? Why are we nourished by it?

I don’t think Sontag ever answered that question honestly. She never let herself think the problem of seriousness through. She was scared that it would have driven her, maybe, down the same path that it drove Simone Weil. Sontag wanted, in the end, to appreciate Simone Weil—but from a safe distance.

This has everything to do with God, of course. The fear of God. Not in the biblical sense of fearing God, which is fear as a sign of respect and awe. But actually being afraid to talk about God. Sontag had that fear. She wanted to pick her way around the talk of God, to extricate the core of “seriousness itself” from any of the theological baggage in which it has been packaged over the ages.

Easy to sneer at Sontag for that. Easy to understand her fears, too.

Sontag wrote that Weil is “the person who is excruciatingly identical with her ideas, the person who is rightly regarded as one of the most uncompromising and troubling witnesses to the modern travail of the spirit.” Couldn’t the same be said of Sontag? Isn’t the “modern travail of the spirit” just the struggle to keep the word spirit alive?

In her own way, Sontag was doing that. Her defense of seriousness was a defense of spirit under another name. She was trying to smuggle spirit through the trials of modernity, even if she never fully realized that was what she was doing. She was trying to make it safe to talk about the highest things within a milieu that was all about collapsing the high and the low.

Sontag perhaps feared the full impact of Simone Weil’s writing, but she understood what Weil was saying. “In the respect we pay to such lives,” Sontag wrote about the life of Simone Weil, “we acknowledge the presence of mystery in the world.” Is that what Sontag was really trying to do, lying on that bed with her dark sweater in 1975, looking serious and large? Was she trying to find a way to acknowledge the old mysteries that, by 1975, had seemingly been laid to rest?

Morgan Meis is the critic-at-large for The Smart Set (thesmartset.com). He has a PhD in Philosophy and has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, and The Virginia Quarterly Review. He won the Whiting Award in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. He can be reached at [email protected].