From the mid-1980s through the early 1990s, I devoted my research and writing to the nuclear arms race and nonviolent responses to it. The mid-eighties marked the height of the Cold War. The U.S. and the Soviet Union were locked in an arms race that our government referred to as (I kid you not) “MAD.”

From the mid-1980s through the early 1990s, I devoted my research and writing to the nuclear arms race and nonviolent responses to it. The mid-eighties marked the height of the Cold War. The U.S. and the Soviet Union were locked in an arms race that our government referred to as (I kid you not) “MAD.”

The acronym stood for Mutually Assured Destruction.

The strategic theory behind MAD was that if both nations had enough nuclear bombs to totally annihilate the other country and its inhabitants, then neither nation would push the button—because even after a first strike by one side, the other side was capable of launching a second strike in retaliation. Second strike capability was housed mostly in nuclear submarines that cruised the ocean floors.

By 1988, the U.S. had about 23,5000 nuclear bombs in reserve, the U.S.S.R about 33,000. Overkill, to put it euphemistically.

Feeling maddened by MAD, I joined several anti-nuclear organizations, received all their newsletters (this was of course in snail-mail days): Union of Concerned Scientists, Council for a Livable World, Natural Resources Defense Council, and more. I saved all these mailings in huge boxes in my attic.

Coming to anti-nuclear activism from the academic field of semiotics, I got interested in the discourse of the nuclear weapons debate. I subscribed to magazines on both sides of the debate and bought piles of books on the topic. I saved all these materials in huge boxes in my attic.

But I also began studying nonviolence, inspired by Thomas Merton. The spirituality of nonviolence taught me to seek the good in the “enemy,” that in my case wasn’t the Soviet Union but rather the pro-nuclear people in my own country. I subscribed to periodicals like Fellowship and Sojourners to learn more about the spirituality and practice of nonviolence. I saved all these magazines in huge boxes in my attic.

Nonviolence told me that I must learn to see the world from the “enemy’s” viewpoint. So I left my New York home for a year to go to New Mexico’s Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), where nuclear physicists were designing ever more “sophisticated” bombs. My friends in the anti-nuclear movement assumed I was going to Los Alamos to join in protests; but, no, I was going in order to listen to the physicists talk about why they’d chosen to put their careers at the service of MAD.

I talked with many of the physicists; I attended LANL’s public lectures. I was invited to sit in on a discussion between a visiting Soviet nuclear physicist and his Los Alamos counterparts. Their friendly repartee astonished me: like rival football coaches having a beer together after the game, they laughed “well, if you do this, then of course we’ll do that to you.” I made voluminous notes on all my Lab experiences, and saved them in a box in my attic.

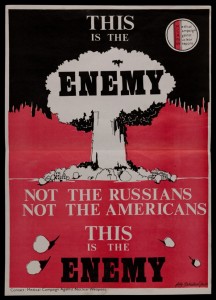

While at Los Alamos, the semioticist in me got intrigued by the mushroom cloud image and the various meanings then being imposed on it.

I visited the Los Alamos museum, with its photo-wall of specific atomic explosions. Like baby pictures, the mushroom clouds were captioned with names: “George, May 8, 1951”; “Charlie, Oct. 30, 1951”; “Mike, Oct. 31, 1952.”

I stood before the five-foot-high mushroom cloud poster at the museum’s entrance, with its text justifying LANL’s existence:

If peace is viewed as the absence of general war among major states, the world has enjoyed more years of peace since 1945 than has been known in this century; and nuclear weapons have been a major force working for peace in the postwar world. They make the cost of war seem frighteningly high, and thus discourage nations from starting wars that might lead to their use.

This is MAD run through a rhetorical “peace” machine, I thought.

In the museum gift shop, I bought postcards of the named mushroom clouds and brought them home for an attic box.

Meanwhile, I’d seen a newspaper article about Richland High School, near the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in the state of Washington. The school emblem was a cartoon mushroom cloud, its geyser bubbling up with adolescent energy—perfect emblem for the school’s sports teams, or so most residents thought. I stashed the article in an attic box along with mushroom clouds cut out from some of my anti-nuclear mailings, where the very same mushroom cloud was an image of monstrous evil.

Up in my attic recently, I stared at all these boxes from my long-ago fifteen-year obsession. The nuclear arms debate subsided with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Mushroom clouds faded from the popular imagination. Despite the little-known fact that the U.S. currently stockpiles and continually “modernizes” some 7,700 nuclear bombs, at a cost of $372 billion annually, the topic has disappeared from both public and private conversation.

Contemplating my heaps of boxes, I knew I’d never again open them. Our life has phases, and this one—as stimulating as it had been—was from a past I wouldn’t return to. The boxes had to go. But I hated just to haul them to the curb for recycling.

My husband had an inspiration: “They’re of historical value. Maybe the Gandhi Institute would want them.”

Backstory: when Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson Arun Gandhi moved to my city about eight years ago to be near his own grandkids, he brought with him the M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence. I emailed the Institute, described my boxes of materials, and offered them. “Yes, we’d love them,” was the reply.

A few days later, one of the staff came to pick up my half-dozen huge, heavy boxes. As he loaded them into his car, I felt a bit empty at seeing fifteen-plus years of my past go out the door. But I also felt gratified that my collection had found the right home. I let myself picture my books and magazines and newsletters on the Gandhi Institute’s shelves, where anyone from the public could go in and read them. Maybe the nuclear cloud photos would be hung on the wall above, so a new generation could get a sense of the MADness of that era.

Peggy Rosenthal is director of Poetry Retreats and writes widely on poetry as a spiritual resource. Her books include Praying through Poetry: Hope for Violent Times (Franciscan Media), and The Poets’ Jesus (Oxford). See Amazon for full list. She also teaches an online course, “Poetry as a Spiritual Practice,” through Image’s Glen Online program.