Today we bid farewell to regular contributor Bradford Winters who has written more than 100 posts for “Good Letters” over the years. We extend our gratitude and best wishes to him.

Today we bid farewell to regular contributor Bradford Winters who has written more than 100 posts for “Good Letters” over the years. We extend our gratitude and best wishes to him.

Situated as we are in early November at a midpoint between the end of the High Holy Days in the Jewish calendar and the start of Advent in the Christian one, it seems like the right time to include such a baldly titled book on the Church’s general Christmas wish list.

For after “twenty centuries of stony sleep,” to quote W.B. Yeats in “The Second Coming,” far too many of us who subscribe to the latter calendar will wake up once again on December 25 in an unwitting fog of continuing ignorance or indifference with regards to our Judaic heritage as Christians, meaning literally, “sons of Christ.”

The patrimonial import suggests it might be a good idea to gain a better sense of where this whole Christian thing actually came from, which was certainly not a vacuum carved out by a rebellious peasant from Nazareth determined to sabotage the tradition that preceded him.

I wouldn’t presume to give a primer in this short space on a subject so vast, but perhaps only a taste or a fragrance, a whisper or a glimpse, of what one might feel like.

Let me make a caveat at the outset, which is that I’m a dummy, too. Maybe less so than I was a few years ago before my interest in the subject took root, but this is hardly an act of pedagogical condescension on my part. I’m down here with you, in the muck of much misunderstanding.

So let’s get started.

Open your Bibles to—no, on second thought, open your dictionaries. To supersessionism: the once widely held belief that the Church is “the new Israel” and has replaced its forbear as God’s chosen people. Hence the synonymous term, “replacement theology,” which has largely fallen out of fashion in modern times among the mainstream Church, thanks in part to the underlying complicity with the Holocaust it stood accused of in the aftermath.

Such doctrine may go unspoken for the most part today, but has it truly been replaced, or does it linger in the air and church pews?

Has it been superseded by a more unifying theology that finds the Old Testament’s imprint all over the New, so much so that more of us might adopt British scholar Margaret Barker’s usage of the term “Older Testament” so as to refute the subtle sense of pejorative discontinuity that old connotes?

Do we subscribe to a theology that hammers home, for example, the Levitical “good news” of the Letter to the Hebrews—not the most popular text in many of today’s pulpits but perhaps the most gorgeous for rhetorical sweep—or do we give lip service to the fact that “Jesus was a Jew” and then get back to Christianese? Why Christianese? Because Christianity makes no sense whatsoever without a proper understanding of its Jewish roots.

Jesus of Nazareth was crucified for our sins? What? Why?

Raise your hand if you’re Christian and you don’t really know what Yom Kippur is, the climax of the High Holy Days and liturgical year in the Jewish calendar. Don’t be shy; no one’s looking. It’s just you and me, and I can’t even see you.

For those of you with your hands down who know it was and is the Day of Atonement, do you know how this atonement was accomplished?

How one day a year, in a sacrificial system that prescribed individual offerings for personal forgiveness, the High Priest would transfer all their sins onto an unblemished animal which was then slaughtered in their stead; after this he would take its blood into the tabernacle and sprinkle it on the mercy seat for corporate atonement on behalf of not only all Israel but all creation.

Italics mine; or rather, ours.

Thanks in part to the film industry that I work in, we tend to remember to a cinematic extreme God’s first dispensation to Moses atop Mt. Sinai with the Ten Commandments, yet overlook or altogether forget the second with plans for the tabernacle. We tend to remember the wrathful God of the Old(er) Testament, yet overlook or altogether forget the God who in the same breath gave Moses not only the Law but also the solution which would allow the Israelites to atone upon inevitably breaking it.

Now raise your hand if you’re starting to sense an antecedent to the Gospel that perhaps you never noticed or rightly understood.

Perhaps an often vexing verse like Matthew 5:17 now begins to make a bit more sense: “Think not that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets; I did not come to abolish them but to fulfill them.”

Their respective first uses of the word tabernacle provide our first clue to the theological bridge between the Old(er) and New Testaments: whereas Exodus employs the wordas noun in God’s command that Moses build him a sanctuary, John’s Gospel uses its verb form meaning “to dwell.” A more illuminating translation of the prologue’s central verse might be: “And the Word became flesh and tabernacled among us.”

The tent that dwelt at the center of the Israelite encampment in the wilderness with animal skins for a covering found its counterpart in the One who dwelt likewise with such skin for a covering.

“Of these things we cannot now speak in detail,” the author of Hebrews writes. Thankfully, his epistle nevertheless goes into quite a bit detail along the same lines that concern us here, and serves as a far more comprehensive primer than I could even begin to deliver.

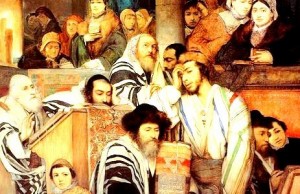

Read it if you haven’t already. If you have, but not in some time, read it again. And if you’re up for it, find your way to a Messianic synagogue—either in person or via Internet streaming to see and hear what it’s like to worship as a Christian in a Jewish setting, much in the same way the early Jewish Christians did.

On that unifying note true to the spirit of “Good Letters” and Image journal, I say a heartfelt goodbye. Thank you for reading and commenting these past six years.

Bradford Winters is a screenwriter/producer in television whose work has included such series as Oz, Kings, Boss, and The Americans. His poems have appeared in Sewanee Theological Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, and Georgetown Review, among other journals. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and three children.