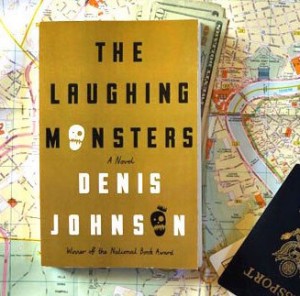

On the back cover of Denis Johnson’s new novel The Laughing Monsters is a rather extraordinary quote by David Means. Means was reviewing Johnson’s short novel, Nobody Move, for the New York Times Sunday Book Review in 2009.

On the back cover of Denis Johnson’s new novel The Laughing Monsters is a rather extraordinary quote by David Means. Means was reviewing Johnson’s short novel, Nobody Move, for the New York Times Sunday Book Review in 2009.

The sentence from the quote that struck me in particular is that Johnson “routinely explores the nature of crime—all his novels have it in one form or another—in relation to the nature of grace (yes, grace) and the wider historical and cosmic order.”

Crime, grace, and the wider historical and cosmic order. A novel by Johnson is, then, according to Means, practically the Bible. Maybe better.

Of course, David Means is pretty sure we will not believe him. That’s why he mentions grace twice.

There is good reason not to believe that Denis Johnson’s fiction has anything to do with grace. Denis Johnson writes depraved stories of sex, violence, excessive drug use, theft, murder. The narrator and protagonist of The Laughing Monsters (Roland Nair) has sex with an underage prostitute in Sierra Leone within the first fifteen pages of the book.

This behavior does not lead to the man’s soul being saved. No souls are saved in the book. No one learns anything. Nothing changes.

The last lines of the novel are “I’m inclined to believe it.” This is not a reference to the Gospel message. It is a reference to yet another crazy scheme to hustle a big score. Throughout the 228 pages of the novel, crazy schemes always lead to mayhem and death.

The entire plot structure of The Laughing Monsters is a circle. At the end of the book, if you want to know what is going to happen next, you can simply turn to the first page of the book and start reading again. The characters are all caught in a terrible loop.

Roland Nair is a man willing to believe that, somehow, his dreams of a big take in Africa—or some other place far away from his home country of Denmark—are going to come true. He has no good reason to believe this. His partner in crime, an African named Michael Adriko, is quite plainly a delusional con man.

But Roland Nair does believe. He will go on believing. His continual belief that “something big is going to happen” will, indubitably, generate more suffering for himself and everyone else involved. Ad infinitum.

Why do Nair and Adiko continue in their delusional fantasies? Nair tries to explain himself in an email to his erstwhile girlfriend, whom he is in the process of betraying:

I won’t outrage you with pleas for forgiveness. I hope you hate me, actually, as much as I hate myself. And no explanation—nothing you’d understand—only this: the other day Michael asked me if I really want to go back to that boring existence. I said no.

Let’s go ahead and call Roland Nair a searcher. Searchers have the tendency to hurt people. They hurt themselves, which they probably deserve. They also hurt the people around them. That’s because they are willing to do almost anything not to “go back to that boring existence.”

It can be mentioned here that Denis Johnson knows what it is like to be a desperate searcher. He was a drunk and a drug addict for a good chunk of his early adulthood. He wanted what he wanted when he wanted it. He did what he had to do to get there.

Searchers like Johnson are looking for something, but since they don’t know what it is, the looking and the not-knowing produce a tremendous amount of pain.

All of this brings us back to grace. Because you don’t get out of the infinite loop of desperate searching until something happens—something beyond your control. Another name for “something happening” is grace.

So, David Means wasn’t crazy when he said that Denis Johnson’s novels explore the nature of crime and grace. But there is something disturbing to the thought that crime and grace are somehow related. It is unpleasant to contemplate the possibility that crime may be a surer road to grace than goodness.

Except that you must contemplate this problem if you’re going to contemplate grace. The problem goes all the way back to Paul. What thinker is more fundamental to the Christian conception of grace than Paul?

Paul’s story begins, when he was still named Saul, as a crime story. Paul stood there guarding the cloaks of the men who performed the extra-judicial murder-by-stoning of young Stephen. Did witnessing this murder turn Paul’s heart? Not at all.

“And Saul was consenting unto his death.”

But not only consenting. Paul was fired up for more persecution. He was excited by it.

“As for Saul, he made havoc of the church, entering into every house, and haling men and women committed them to prison.”

In essence, it is this period of havoc that Denis Johnson explores in his novels. Havoc is something more than just bad behavior. It is different than crime committed for a specific purpose.

Havoc is what happens when crime comes of a desperate need that can’t be explained. Maybe all crime has this root. But it becomes havoc when it is grasping, ruinous, and utterly self-defeating.

When a man or woman reaches the point of havoc, he or she is, paradoxically, very close to grace. The place of havoc is a tense and terrible place to find oneself. But there is wonder in it too, because God is nearby.

Think of the prodigal son lying in pig shit and realizing that he wants to go home. The havoc has turned into grace. The moment just before he surrenders, when the prodigal son is considering one last tear through the town, that’s the moment that Denis Johnson captures in novel after novel.

Morgan Meis is the critic-at-large for The Smart Set (thesmartset.com). He has a PhD in Philosophy and has written for n+1, The Believer, Harper’s Magazine, and The Virginia Quarterly Review. He won the Whiting Award in 2013. Morgan is also an editor at 3 Quarks Daily, and a winner of a Creative Capital | Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant. A book of Morgan’s selected essays can be found here. He can be reached at [email protected].