Sean was not an easy child to raise. My husband and I became his parents through adoption and met his birthmother prior to his birth. Young, freckled, and sweet, Janet decided to have a C-section and asked me to be present although she’d be unconscious herself.

Sean was not an easy child to raise. My husband and I became his parents through adoption and met his birthmother prior to his birth. Young, freckled, and sweet, Janet decided to have a C-section and asked me to be present although she’d be unconscious herself.

On the scheduled day, I stood in an operating room wearing surgical scrubs. Nurses buzzed around, readying forceps and scalpels. An anesthesiologist worked Janet’s IV and checked the electrocardiograph. Janet drifted off, breathing slowly and steadily, her bare belly bulging from a sea of deep blue cloth.

The obstetrician came into the room, holding out freshly scrubbed forearms and hands. He chose a scalpel from a tray as the nurses gathered around. Poising its tip below Janet’s navel, he nodded at his assistants.

A quick slash, a glint of steel. A swarm of elbows and hands like bees around a hive. A bloody eel slithered from the wound—the umbilical cord—and hung between the table and the doctor’s hands. I couldn’t see the baby, just the doctor’s back.

The doctor fussed a bit and looked at me. “Jan, I need your help.” He motioned to a tray with his elbow. “You’ll need the scissors and the clamp.”

Moving beside the doctor, I took the instruments from the tray, slipped the scissors on my fingers. I turned to my first glimpse of Sean—his slimy, bloody body, his writhing head and limbs. I spread the scissor blades apart, cut and clamped the cord, then stroked Sean’s tiny wrist, his eyes opening for a moment, flickering gray-green.

A nurse picked Sean up, weighed him, and showed me how to sponge-bathe him: “Pay special attention to creases under the arms, behind the ears, around the neck, in the diaper area, and to the spaces between the fingers and toes. Then clean the cord stump with a cotton swab dipped in alcohol.”

She also showed me how to swaddle him: “Place him face up on a blanket, pick up a corner, wrap the blanket around his body—snugly, but not too tightly, being careful of the cord—and tuck the blanket beneath him, leaving his head and neck exposed.”

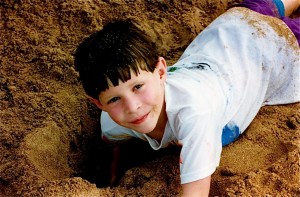

I can’t begin to count the times I cleaned and swaddled Sean in the days and years that followed, even after his baby fat and folds gave way to the long, lean body he’s possessed since toddlerhood. From the moment Sean discovered that he had the power to propel himself, he had a penchant for risk, adventure, imprudence, the forbidden, and injuring himself.

One time, when he was four years old, I left him in his bedroom napping soundly—his eyes rolling in their sockets, his breaths even and deep. I took advantage of the moment to collect some laundry from the dryer and was busy folding clothes when I heard a crash and screams.

I ran to Sean’s bedroom. There I saw a toppled highboy dresser, its drawers half-sprung, their contents spilling out. A tiny arm and leg protruded from the rubble. Sean was shrieking, “Mommy, Mommy, hep!”

As I righted the highboy dresser, a drawer unexpectedly slid fully out and tumbled on my son, adding insult to injury. Heart pounding, eyes tearing, I pulled Sean from the wreckage: his bones seemed to be unbroken, but blood spurted from a deep laceration in his head.

Frantic, I picked up my son and carried him to the bathroom, where I laid him on the floor. Blood puddled on the tiles as I tried to stop the bleeding. I cleaned the gash and dressed it with gauze pads and fabric tape. Then I wrapped Sean in a towel, drove him to the ER, and held his swaddled, squirming body as the doctor sutured the wound.

Later, after the stiches, Sean told me he’d wanted to reach a stuffed “aminal” that I’d left on top of the dresser, but being short, he opened some drawers to use as a ladder up.

That was just one of many gashes I cleaned and bound as Sean went though his childhood and tween years and took up skiing, soccer, hiking, whittling, baseball, biking, climbing, and punching bullies who roughhoused kids at school. But while his early wounds were literal, those I tended later were metaphorical.

When Sean was a sophomore at college, he called right before Thanksgiving to confess he’d not been to classes since October when a close friend had drowned in a lake. Instead of doing any work, he holed up in his dorm room drinking beer, smoking weed, writing poems, and entertaining girls. His professors and advisors had informed him it was too late to make up his assignments, so he would fail all of his courses and be suspended for the academic year.

Hearing this, I jumped into the car and drove four hours through a blizzard to meet with Sean’s advisors. I argued Sean was suffering from depression and brokered a medical withdrawal: he’d receive no Fs, saving his GPA. The suspension would have to stand, though, so I helped Sean move out of his dorm room, piling clothes, books, and skis into car with the snow careening down.

At home, I gave Sean his orders: He would go to counseling until March, then begin a leadership program where he’d spend three months in the wild learning outdoor skills and studying ecology. In the fall, he’d return to school.

Right or wrong, I once again attempted to clean and swaddle my son. And I did it over and over for the next five years as Sean meandered towards adulthood: for every two steps right and forward, he took one step left and back, and for each misstep he took I stepped in to get him back on track.

Last summer Sean earned a BA in environmental education and a certificate to work as an emergency medical technician. Since the road had been arduous and long, we made plans to celebrate his milestones by walking a comparable path, The Way of Saint James in Spain. Nonetheless, despite Sean’s accomplishments, I harbored doubts that he’d actually matured.

To be continued tomorrow.

Jan Vallone is the author of Pieces of Someday: One Woman’s Search for Meaning in Lawyering Family, Italy, Church, and a Tiny Jewish High School,which won the Reader Views Reviewers’ Choice Award. Her stories have appeared in The Seattle Times, Good Letters, Faith & Values in the Public Square, Catholic Digest, Guideposts Magazine, English Journal, Chicken Soup for the Soul, and Writing it Real. She lives and teaches writing in Seattle.

Photo above belongs to Jan Vallone.