By Paul Mariani

Note: We asked the author, one of Image’s editorial advisors, to write a tribute to his longtime friend, the late poet Philip Levine.

It was at the Breadloaf Writers Conference back in the late 1980s that I first met Phil Levine. The summer before, Bob Pack had asked me for the names of some poets whom he might invite to the conference, and I mentioned how great it would be to invite Phil.

It was at the Breadloaf Writers Conference back in the late 1980s that I first met Phil Levine. The summer before, Bob Pack had asked me for the names of some poets whom he might invite to the conference, and I mentioned how great it would be to invite Phil.

I was deeply drawn to Phil’s poetry for a number of reasons—his working-class background growing up in Detroit, much like my own growing up in Mineola, Long Island, the way he wrote about people in factories or in diners or at bus stops which most poets overlooked or disregarded, though certainly Walt Whitman had sung of them, as had Robert Frost and William Carlos Williams and Charles Olson and Muriel Rukeyser and Theodore Roethke. Anyway, that was a big part of the draw.

And then there was the fact that I was writing a biography of John Berryman, and Phil had not only studied with him at Iowa, but had been as drawn to him as I was, and as he would make clear in a piece he wrote called “Myne Own John Berryman.”

So there we were, on the mountain up in Ripton, Vermont—a mile from the cabin where Robert Frost had written so many of his poems and who had come to know Berryman there thirty years earlier when Berryman was deep into his Dream Songs. And there was Phil and his wonderful wife, Franny, and Garrett Hongo and Eddie Hirsch, and Eddie took me aside one afternoon and told me that Phil liked me, which was a relief, because if he didn’t you knew it pretty quickly.

There’s a photo of us someone took of us which I cherish. I have my arm around Phil—I just felt that close to him—and we’re both grinning. And the sun is shining on us and in that snapshot we have all the time in the world.

I love his poems, whatever they sing about—whether that’s Fresno, where he taught two generations of poets, or Detroit, where he grew up in the 1930s and ’40s and early ’50s and worked at a number of thankless jobs, about which he has written with such angry, raw beauty. Or whether it’s Manhattan or Brooklyn—when he taught at NYU and to which he returned to his apartment on Willow Street with the lovely Franny, with his three sons and their families nearby. Or whether he was singing of Spain—the Spain of the 1930s with its terrible civil war, or when he returned to live there in the turbulent 1960s.

There’s a mystical quality to Phil’s poems, the way he refuses the consolations of the world, even as he yearns for those same consolations. The way he smashes the smug face of racism and anti-Semitism and intolerance. The biting wit. The rage of “They Feed They Lion.” Black graffiti on some factory wall.

The humor—the way he could make me laugh so hard I had to beg him to stop so that I could get my breath back, and then he’d be at it again. The way he saw through the scrim of things and got at the heart of the matter with his no-nonsense bullshit detectors. The mercy of it, the way he deeply felt another’s pain. The way he’d catch you and simply say, “Paul, do you really believe that?”

Then there are his wonderful letters, especially from the 1980s and ’90s and early 2000s, when folks still wrote letters and before emails took their place. And the times we poets gathered to celebrate his having arrived at a particular birthday, his year as Poet Laureate of America, his deep knowledge of Spanish poetry, of the blues and jazz, his deep understanding of the black experience in America, the sacrifices of those who fought against Franco, and most of all just his presence, which was such a gift for me.

I suggested on several occasions that I’d love to write a biography of him, but he was having none of that. You want to be my friend, right, he said, the intimation being that if I wrote his life, something more intimate would go out of the relationship. It was something which—if I didn’t understand—I was at least willing to honor.

The last time I saw Phil and Franny was at their Willow Street apartment in Brooklyn. It was shortly before Halloween. He seemed fit as ever and he loved to walk. So we walked the streets of Brooklyn Heights as evening came on and I asked some stranger (a young Englishman with his girl) to take a picture of Phil and me, with the East River and lower Manhattan and the Brooklyn Bridge for background, then it was back to the apartment for a shot of the best Polish vodka I’ve ever tasted.

And then we walked over to a Polish restaurant a few blocks over which he and Franny loved to frequent. It was a good meal, and great service by a young Polish woman, and, when it came time for the check I said, “We’ll get the check now,” speaking with that papal we, and he shot back, with that sly grin of his: “No, you’ll get the check.” Which was fine with me, of course, but I couldn’t help laughing with the comic Jewish brusqueness of it, and then, under a night sky glowing with electric lights, he and Franny walked me to the train station under the old St. George hotel, where I hugged them both and then turned as they disappeared and descended into the subway (the same one Hart Crane used to take into Manhattan and the one I showed James Franco when we made that film of Hart Crane), and then Phil was gone.

When I wrote Eddie Hirsch with my sad condolences about our mutual loss, he wrote back to say that he missed Phil and all he wanted now was his friend back. I want him back too and still can’t believe he’s really gone. But we’ll just have to get used to the fact that he belongs to the ancients now, his pure poetry whispering its way through the streets of Detroit and the hills outside Fresno.

Paul Mariani is the University Professor of English at Boston College. He is the author of five biographies (William Carlos Williams, John Berryman, Robert Lowell, Hart Crane, and Gerard Manley Hopkins) with a sixth on Wallace Stevens to be published in April 2016, as well as of seven volumes of poetry, four critical studies, and Thirty Days, an Ignatian spiritual memoir. His relationship to Image goes back to the beginning and is long and deep.

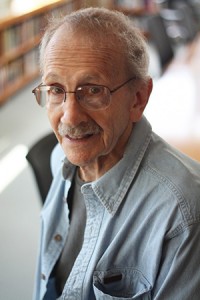

Pictured above is Phil Levine.