Continued from yesterday.

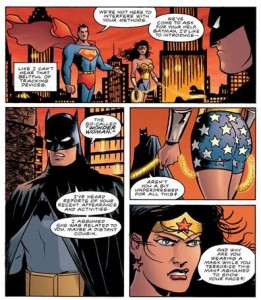

In this scene from Batman’s first meeting with Wonder Woman in Trinity, you can feel the writer Matt Wagner’s personality trumping the artist; though it doesn’t really add much to the narrative, Wagner can’t help but let Bats make a crack about her costume.

In this scene from Batman’s first meeting with Wonder Woman in Trinity, you can feel the writer Matt Wagner’s personality trumping the artist; though it doesn’t really add much to the narrative, Wagner can’t help but let Bats make a crack about her costume.

Superheroines’ costumes are perpetually controversial, it seems (perhaps because few artists have done much to better protect their heroines), and I sympathize with those who critique the way women are often overly sexualized in ways men are not. I don’t agree that the antidote is more sexualized male bodies. That strikes me as the kind of capitalistic, individualistic, hedonistic thinking that led to the hypersexualization of all bodies at the magazine racks. But at the same time, I also don’t believe we need more realistic bodies or body armor in all cases.

Take Wonder Woman flying, for instance. Yes, it stretches the suspension of disbelief to breaking to put her in a strapless one-piece “armor” (and yes, it is frequently referred to as armor; if you look, you’ll see the chest-piece and waistband are, in fact, metal). Some newer series and geek blogs have tried to re-imagine her costume in more realistic terms with some success, but increased realism comes at the cost of bringing Diana closer down to earth.

Now, while in my previous post I called Wonder Woman an icon of transcendent hope, I wouldn’t want to suggest her iconicity matters more than her humanity. It is important to me that Diana is a person with an inner life and a personal history, but it is important to the character of Wonder Woman that she remain just this side of totally individual, because it is part of her mythological function to receive our hopes and desires for goodness onto herself.

Pérez’s drawing captures the individual/icon dynamic in the way he shows us a young woman enjoying the power and beauty of her own body. Her eyes are closed and she’s smiling, taking a moment to herself after an unimaginably stressful day of trying to convince patriarchy’s children of a better way.

She abandons herself in a field of play where her powers are not called upon for any purpose other than the joy of having them. Her body is lean and agile and she loves how the wind curves across it. Her posture signifies not power but moral innocence. In this picture she is the opposite of Batman and purer than Superman.

Granted, she still wears the implausible unitard that shows a lot of skin, and even as self-aware as Pérez is, there’s no escaping the pervasive comics interest in the hero’s idealized, often exaggerated body. I have my list of characters whose costumes or features exceed good taste (Ms. Marvel and Black Cat pretty well take the cake on this; next to them, Diana’s costume is as scandalous as a swimsuit), but in this case I don’t think it is an intrinsically sexual image, and I read her idealization as serving a legitimately transcendent purpose.

Make no mistake, even Pérez has other female characters become body-conscious around Diana, but Diana herself never looks at other women as anything other than sisters. Pérez, at least, never presents her as eye candy for a male readership; and this is important because Wonder Woman has always had a female empowerment dimension to her (which I never realized until learning about her creator).

Beauty for superheroines generally alternates between the Greek ideals of symmetry and proportion and straight-up male fantasy. Certainly either can serve the shame-based body-ideals of our consumer age, but I can’t help reading Pérez’s work against that tradition.

I don’t think it’s going too far to say that in his hands (and some others’), Wonder Woman’s beauty is sacramental. Physically, she represents the goodness of the body—that movement is itself a kind of freedom, that sensation underlies much of our joy and pleasure, that a body is a fearful and wonderful thing in itself. We see hints of this in how her arms are lengthened beyond proportion but her face expresses a private experience; she is both impossible ideal and her own person.

In our age of internet porn and sexting, when the most recent controversy about Wonder Woman was whether Gal Gadot, who will play the role in Superman vs. Batman, is muscular enough or has large enough breasts (conversations that don’t merit links), I think it’s worth reminding ourselves over and over that beauty is not always reducible to the sexual nor only merely a tool for a powerful group such as white men.

Superheroes—male and female—have come to constitute part of the American psyche for more reasons than nostalgia or escapist fantasy. They are the closest thing we have to a national pantheon (as distinct from our hall of heroes), and their popularity does not preclude their spiritual significance.

Wonder Woman can be both an individual beckoning the same moral response we give other fictional characters and a sacramental image of incarnate being; she’s most fascinating when she can transform this tension into a harmony.

Wonder Woman flying reminds us that playing basketball, running, dancing, even just stretching in the morning, all uses of our bodies, whatever our limitations, express their created goodness. The little skip over a puddle, the victorious fist pump, even a comically raised eyebrow, it turns out, are all forms of flying.

Brad Fruhauff is a film buff, comics nerd, literature scholar, editor, and writer living in Evanston, IL. He is Senior Editor at Relief: A Christian Literary Review and a Writing and Communications Specialist at Trinity International University where he also serves as Contributing Editor for Sapientia. He has published poems, essays, and reviews in Books & Culture, catapult, Christianity and Literature, Englewood Review of Books, Every Day Poems, Not Yet Christmas: An Advent Reader, Rock & Sling, and in the newly released How to Write a Poem.