On December 10, 1968, Thomas Merton stepped out of the shower in his Bangkok hotel room, reached to adjust the speed of a fan, and was fatally electrocuted.

On December 10, 1968, Thomas Merton stepped out of the shower in his Bangkok hotel room, reached to adjust the speed of a fan, and was fatally electrocuted.

In many ways, Merton foresaw his own death. And though he could never have imagined it exactly, it was filled with the kind of intent irony and poetry that his life as a contemplative monk/author/peace activist embodied.

As a Trappist monk, he was, by definition and order, cloistered. According to the Rule of Benedict, he was to avoid idle speech, and to live by the work of his hands. But as is well known, Merton struggled to stay silent and disengaged from the world.

His writings, especially his essays and the celebrated autobiography Seven Storey Mountain are characterized by a deep concern for the world and how we are to live in it without being of it.

I walk to work every day, partly because we are a one-car family and partly because I enjoy the fifteen minutes of solitude. Lately, I have been reading as I walk, it helps me to be more contemplative.

I walk and read until I come upon a passage that strikes me, then I stop, take the pencil tucked behind my ear and underline the phrase, or star the section, or jot some note in the margin, and then I start walking again until something on the page stops me with its beauty and poignancy.

Even though I am alone in my office for hours every day, I find it hard to read there because my computer is constantly delivering email and fresh Facebook statuses, and the achingly blank Google search field is constantly inviting me to fill it with search terms for an essay that is not really lacking in research.

Walking from our house, I pass by what used to be the college’s dairy. Two of the barns are still standing, one silently rots, and the other has been retrofitted to house art studios and classrooms.

Students complain that the Art Barn is too far from the center of campus. Although it’s only a quarter mile or so, it seems to me fittingly removed. It is one of the only places on campus where the wireless Internet signal doesn’t reach and where cell phones get spotty to no reception. So walking there one is forced into being alone with oneself.

When I discovered that December 10 was the anniversary of Merton’s death, I grabbed my copy of Raids on the Unspeakable and began walking. I skipped to “Rain and the Rhinoceros” which begins with a long and lovely meditation on being alone in a cabin in the woods listening to the “immense and confused” sound of the rain.

Merton has just cooked his dinner of oatmeal on a Coleman stove and toasted a piece of bread at the hearth and now he sits back and listens to what the rain says: “all that speech pouring down, selling nothing, judging nobody, drenching the thick mulch of dead leaves, soaking the trees, filling the gullies and crannies of the woods with water, washing out the places where men have stripped the hillside!”

Trappists, by the Rule of Benedict, are supposed to strive for “stability, fidelity to Monastic life, and obedience.” Talking is limited because it “disturbs a disciple’s quietude” and his “receptivity” to God, and yet Merton’s winding, lyrical meditations lead him, ultimately, to what is disturbing, wounded, and out of order; in this case, the bulldozed swath of forest nearby.

As a writer and human being, I’m under no such orders. I often run afoul of Benedict’s mandate that talking should never inspire “unkind amusement and laughter.” My mind is frequently unquiet, and I’m not as receptive to God as I should be. That is why Merton, who struggled to balance monastic life with the individuality and freedom of the writing life, is such an important model for me: a father, a husband, a poor sinner, who feels hopelessly compelled to write.

Merton, like all great essayists, through his artful wandering, finally stumbles to the heart of the matter: the virtues of solitude. He arrives here after meditations on how rain is experienced as a useless inconvenience in the city, and on the printing on the Coleman lantern box: “Stretches days to give more hours of fun.”

The whole essay turns on this seemingly benign slogan that Merton resists. He comes to the woods not to have fun but to be more like Thoreau, who “sat in his cabin and criticized the railways.” Merton writes, “We are not having fun, we are not ‘having’ anything, we are not ‘stretching our days.’”

As the essay goes on, he meditates on the Syrian writer Philoxenos who, he quips, “had fun in the sixth century without the benefit of appliances.” Philoxenos writes that the virtue of being alone is that it is lawless: “To be a contemplative is therefore to be an outlaw. As was Christ. As was Paul.”

Sparked by Philoxenos, the essay spirals into the heart of the matter, which is that because it is so difficult to be alone for long in the modern world, and because such a premium is placed on doing, on constantly busying ourselves, constantly filling our eyes with spectacle and ears with sound, we never discover who we really are and what we really need.

Merton’s writings and life are a constant reminder that contemplatives do not hate the world. When we are alone we confront innate spiritual poverty, the realization that we are vulnerable and finite, but also a realization that our many grievances with the world, the many errors and wrongs that we—sometimes silently, sometimes loudly and proudly—enumerate are not actually rooted in the world, but in us.

Sitting in his cabin staring at the white flame of his gas lantern, Merton noted “the utility line is not here yet,” but “when the utilities and G.E. enter my cabin it will be nobody’s fault but my own . . . I will suffer their bluff and patronizing complacencies in silence. I will let them think they know what I am doing here.”

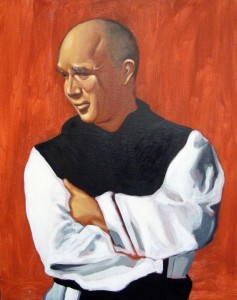

Art above: Joseph Malham, A Portrait of Thomas Merton. Acrylic on canvas.