The alumni magazine of Brown University, my alma mater, begins its article on a unique orchestra like this:

The alumni magazine of Brown University, my alma mater, begins its article on a unique orchestra like this:

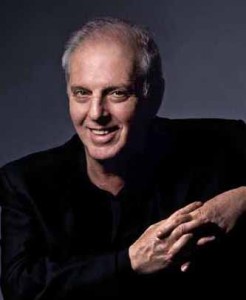

“We are an orchestra against ignorance.” That’s how Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim describes the West-Eastern Divan, which consists of young musicians hailing from Israel and its Arab neighbors.

Picture a teenage violinist from Israel; his name is Ilya. Picture a teenage violinist from Lebanon; his name is Claude. They know nothing of one another’s lives. Or, actually, they think they do know about each other’s lives, because each has been raised on negative stereotypes about the other.

In the late 1990s, renowned Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim and his friend, the late Palestinian-American professor Edward Said, began brainstorming about how to bring these two violinists together, along with other young musicians from the Arab Middle East.

Their goal: to give young people a chance to know each other through the music they would create together.

Barenboim and Said had no illusions that creating the harmony of music would automatically create harmony among peoples who are burdened by histories of hatred and by political leaders who exploit that history. But at least a few young people would have the opportunity for personal contact, would have an opportunity to dispel their ignorance about each other.

Barenboim and Said’s vision materialized in a workshop for young musicians from the Middle East that first took place in Weimar, Germany, in August 1999. The workshop has continued every summer since, in various countries.

At the workshop, Barenboim works the kids hard: he treats them with the same respect and expectation of high standards as his adult professional orchestras. And the hard work pays off: soon the West-Eastern Divan, as the orchestra is named, was performing in major European cities.

Yet maybe a stronger measure of the success of this enterprise is the bonds that form among the musicians. Here are Claude and Ilya, chatting in an outside courtyard at that first workshop.

Claude: “At first it was strange. But soon: we sit at the same stand, so know I know how he plays, and he knows how I play—so we actually have some connection. Now we understand each other more.”

Ilya: “This is the first year, but the workshop must keep going. Even if in two or three years there is peace between Israel and the Arab countries, the workshop should continue—just to bring people together.”

Claude gets angry: “Peace! How can you talk about peace! This is only music!” And he stalks off. Ilya shakes his head with a smile.

A few years later, during audience applause at the end of a concert, the camera shows these two standing with the rest of the orchestra, Claude patting Ilya on the back.

We have this conversation on film—thanks to another artist, filmmaker Paul Smaczny.

It happened that Smaczny was working on a profile of Daniel Barenboim in the late 1990s—just as Barenboim and Said were hatching plans for the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra project. On the website of the film that Smaczny eventually made about the project, he writes, “I thought I would stay and film two or three days to document Barenboim’s activities in reconciling Israelis and Palestinians. I ended up following this unique experience for seven years.”

The result was Smaczny’s 2005 documentary, Knowledge is the Beginning. Knowledge, that is, of people of whom one had been previously ignorant.

As the film makes clear, playing music is the core of the Barenboim-Said project. But the two men sought other ways to open the youths to the others’ experience. During the 1999 summer workshop in Weimar, for instance, they arranged a trip to nearby Buchenwald, the former Nazi concentration camp.

Afterward, Barenboim spoke to Said and to the camera:

There was one Arab kid, after we walked through the crematorium, who came to me; and his face was shaking from what he had seen. And he took my arm and said to me, “You know what I’ve just thought. If we had all lived here, you—whom we respect so much—we, all of us, Arabs and Jews, would have ended here.” In other words, he had to come here to see how close we are—as a Semitic race.

So why was the West-Eastern Divan featured in my Brown University alumni magazine? Because Brown hosted the orchestra for a week this past January. (After their Brown gig, which was accompanied by “painfully open public conversations about the Middle East,” says the article, “they headed to Carnegie Hall, where they wowed New York City audiences with the full Beethoven symphony cycle.”)

Brown is also developing an ongoing relationship with Barenboim and the orchestra.

The next step in Brown’s collaboration with the Divan will center on the founding of the Barenboim-Said Academy in Berlin, which is scheduled to open in 2015. The mayor of Berlin has given space for the school, and the state has pledged $27 million…. Brown faculty members are helping design the academy’s curriculum, a third of which will focus on the humanities, and they will teach there as well…. The academy will enroll students from Israel and its Arab neighbors, as well as from Brown.

I easily fall into despair at the entrenched hostilities in the Middle East. But this collaboration is for me a small sign of hope.

As is Barenboim himself.

Astonishingly hardworking, duly conscious of his fame, he is at the same time humble and gentle, with a wry sense of humor—evident throughout Smaczny’s film and also captured in this small bit from the Brown article:

“We are blessed—or cursed—to live side by side or together. Not back-to-back,” Barenboim said, criticizing both Palestinians and Jews for their lack of curiosity about one another. “I have both an Israeli and a Palestinian passport, so I am in constant dialogue with myself.”