Every winter I plunge into darkness.

Every winter I plunge into darkness.

As Seattle days shorten to eight hours with clouds covering most of the sky and the city readies for ten months of showers, my inner world becomes as bleak as the world outside. I burrow through three seasons like a shrew mole through the mud, tunneling deeper to cry, surfacing only to complain.

Born and raised in New York, I’ve not adjusted in twenty-seven years.

I suppose this isn’t surprising. All my grandparents were natives of Sicily, a place where even in winter daylight persists for ten hours with nary a cloud in the sky. The people of Palermo wake to sun 228 days per year.

When my grandparents immigrated to the US, they did well to settle in Manhattan, where the sun shines over Central Park 235 days each year. The Space Needle basks in sun rays only fifty-eight.

My doctor calls my melancholy SAD (seasonal affective disorder), a depression caused by lack of sunlight resulting in low serotonin. Those who experience it suffer desolation, petulance, anxiety, and social strain.

Since evolution has optimized humans for equatorial light, SAD is common in northern latitudes and climates with cloudy skies. Dark-eyed people like me are genetically predisposed. Blue eyes take in more light. Seattle is simply insufferable for someone with my genes.

I can’t, though, blame my darkness solely on the weather. The past six years have been tough. Just as my children left for college, I lost my full-time job, and I can’t seem to find a new one, thirty years of résumé be damned.

Since I’ve desperately tried to fill the void with a grab bag of pursuits not always suited to me—part-time, volunteer and temp jobs, housework, classes here and there—I’m left feeling frantic, lonely, worthless, bored, and more so every year.

This winter SAD struck hard. I could barely rouse myself mornings, sometimes didn’t bother dressing, cried if my cat crossed my path, overate, skipped the gym, ignored my friends. Every evening I pleaded with my husband, “Get me out of here! There’s nothing for me in Seattle, nothing at all but rain.”

But, in truth, I knew my husband couldn’t leave. He’s worked decades to grow his business and it’s not portable.

Once, I met an American woman vacationing in Tuscany. She told me that although she was married, she always travelled solo and lived alone too. Her husband preferred Boston and she Cos Cob, so they had separate homes.

When I asked the woman if she was ever lonely, she shrugged, “Why should I be? I’m never by myself. My favorite companion is me.”

At this, I remember passing judgment. How selfish. What’s the point of such a marriage? I could never be like her. Still, in the bleak of winter, I determined that I could.

If my husband couldn’t leave Seattle, I’d move by myself.

The idea was so radical and bewildering that my mind could scarcely comprehend it. I’d buy a tiny house. A house in North Carolina, where there are 220 days of sun. I turned on my computer, began to search online, and after ten minutes on Trulia, there my dream home was.

2026 Sycamore Street: The classic 1929 cottage was one-third the size of our Seattle house with lovely lemon shingles, cheerful side veranda, steep pitched roof, and sun-drenched lawn. It had cozy rooms, quaint divided windows, sunbeams angling through the panes lighting the honey hardwood floors.

What relief this house would bring me, so tiny, simple, bright. I’d leave my tattered furnishings behind, discard my old books. I’d spend my time reading Kindle on the porch or planting a garden in the sun—azaleas, honeysuckles, witch hazels, asters, bee balms, goldenrods.

The inside of my cottage would be an uncluttered haven just for me, the outside an ebullient sight for the community. This would be the home of my heart. Thrice daily I ogled it on Trulia, walked around the block on Google Earth. How apt that it was located on Sycamore, for I was sick in love.

One rainy spring morning after dreaming of the house, I came across a poem by Emily Dickinson, as quoted in a Parker Palmer essay:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant,

Success in circuit lies,

Too bright for our infirm delight

The truth’s superb surprise.

Palmer was pondering depression, a state he claims is caused when we disrespect the true self, the person God created us to be.

When we honor the true self, we choose pursuits that employ our inborn talents, resist pursuits that don’t, and heed our natural limitations. Doing so brings us joy and enables us to serve those around us. Doing otherwise causes depression and burdens the community.

To honor the true self, we must listen to the promptings of its voice, which Palmer calls the inner teacher, others call the soul, and others the still, small voice of God. But this voice can often challenge the resistant ego, so to make acceptance easier, it sometimes tells the truth slant, using metaphor.

Could it be that the Carolina cottage was a trope composed by my true self? Not the dwelling I should buy, but the person I should be?

Rather than welcome less square footage, should I embrace my diminished role in the professional world? Instead of shedding tattered furnishings, should I drop unfulfilling work, like teaching basic grammar and dusting the church pews?

Rather than throw out old books, should I discard worn sob stories, like those about my SAD and unemployment? Instead of planting a new garden, should I cultivate pursuits I have and love, like writing and, yes, gardening, and caring for family and friends?

Who would I be if I did these things? On the inside, an uncluttered, tranquil person. On the outside, ebullient, generous.

It seems the brilliant sunlight angling through the Carolina windows is simply the truth about my life told slant. Now it’s summer, and I am listening.

Jan Vallone is the author of Pieces of Someday, a memoir, which won the 2011 Reader Views Reviewers Choice Award and will be re-released in fall, 2013. Her stories have appeared in The Seattle Times, Catholic Digest, Guideposts Magazine, English Journal, Chicken Soup for the Soul, Writing it Real, and Curriculum in Context. Once a lawyer at a large law firm, and later an English teacher at a tiny yeshiva high school, she now teaches writing and literature at Seattle Pacific University.

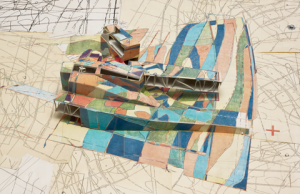

Art above: Douglas Garofalo and David Leary, Camouflage House, 1991.