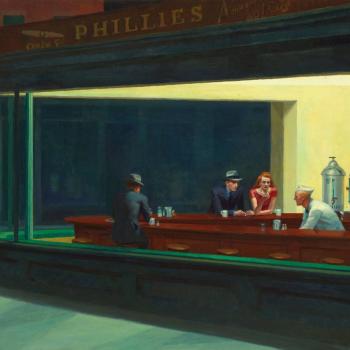

It took me 3 tries to get into Georges Bernardos’ The Diary of a Country Priest. It reads as it’s titled, diary entries of a newly ordained country priest in early 20th-Century France. I jumped into it assuming it would be a pleasant pastoral, an easy read before bed. By the end, I thought, I would feel that the Christian life has some challenges, but overall it’s quite lovely. This is not that book. By the third attempt, I had finally committed to enough pages that I saw something else happening. This priest had a certain indifference to himself, and a jarring preference for doing God’s will in everything. The humanity of the unnamed priest, in all his imperfections and in life’s messiness, sought the one thing necessary in life.

Love in Action

This story echoes Dostoevsky’s famous line, “Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing,” from The Brothers Karamazov. The priest is what we might tritely call socially awkward now, but he knows what he is all about. He engages his parishioners because he desires the salvation of their souls. There is something remarkable about the way he goes after sin, pulling it out of its hiding places to chop off its head, sometimes making a bloody mess of everything. But it’s never about him, never about merely being right and flaunting a superior knowledge of morality. It’s always about God, returning to him, and being prepared to accept his love and mercy. He carries a quiet, disarming courage, but it’s also frightening. Life-changing as others have noted. Not because you might fear being physically intimidated or being berated or humiliated, but because he might just speak the truth to you. An encounter with him might just show you the truth about yourself and about God. You might be left with no other reasonable response than repenting.

Suffering and Grace

The country priest’s painfully short ministry is one whose setting is suffering, in himself and in his parishioners. Yet he doesn’t flinch. He doubts himself, certainly, but he never runs from the situation. He strays in front of the needs of the parish he is given. He knows there is work to be done and grace to be had. In many ways, the climax of the book is a final encounter with Mme la Comtesse, a wealthy parishioner, whose life of sin and suffering is buried under the trappings of wealth. My meager words revealing too much would spoil it here, but the conversations between her and the country priest are intense, to say the least. It becomes clear that he seeks her out for what is ultimately a love for her destiny, rather than putting her in her place. He opens the wounds of her suffering, with the absolute certainty that this is the only path to healing. Whereas most want to run from suffering, he knows there is grace on the other side.

And I know that suffering speaks in its own words, words that can’t be taken literally. It blasphemes everything: family, country, the social order, and even God…A priest can’t shrink from sores any more than a doctor. He must be able to look at pus and wounds and gangrene. All the wounds of the soul give out pus…A priest pays attention to suffering, provided that the suffering is real.

What varied responses we have to the sores suffering, calling the pus of the wounds a character quirk, building our life around avoiding or hiding from those wounds, or rationalizing them away because our neighbors’ are rumored to be worse. The priest reopens the poorly bandaged wounds, attacking the sins that keep them from healing. He brings the wounds and sins out to the forefront knowing full well that acknowledging them is the only way to healing–to mercy and grace.

More John than Jesus

The priest is more a John the Baptist than a Jesus. One who makes room for grace, reminding us of the wounds and darkness we cling to because we have grown comfortable with them.

A man named John was sent from God. He came for testimony, to testify to the light, so that all might believe through him. He was not the light, but came to testify to the light. The true light, which enlightens everyone, was coming into the world…John testified to him and cried out, saying, ‘This was he of whom I said, ‘The one who is coming after me ranks ahead of me because he existed before me.’ From his fullness we have all received, grace in place of grace (John 1:6-9, 15-16).

The priest prepares the way. He follows the light in the midst of all the darkness. He strikes the hardened heart of Mme la Comtesse in order to prepare it for grace: “Blessed would be the sins that left any shame in you. God grant that you may despise yourself.” Out of context, this might ring of harshness, but it comes from knowing that healing cannot happen without the brokenness of a hardened heart, the first step of repentance. It’s John then Jesus. Repentance then mercy. Humility then the crown of glory.

Grace Is Everywhere

The last moments of the priest are reported through a friend from seminary (now a former priest). When his final breaths are apparent, the friend apologizes that the local parish priest hasn’t arrived yet to offer a proper final absolution and to die a more dignified death. The priest replies, “Does it matter? Grace is everywhere.”

Undoubtedly, Bernardos knew of St. Therese of Lisieux’s beautiful response from her deathbed, “All is grace.” But the translation “Grace is everywhere” is entirely appropriate. They are speaking about want of a better situation, but they lack the ability to make the circumstances just a little more ideal. How much time I have wasted trying to tweak circumstances here and there to get them just right? Or worse, avoid them entirely. And that is just the point. In everything he is given, the priest seeks the will of God. Stomach cancer, an indifferent or disgruntled congregation, mentors that fall short, death in a former priest and his mistress’ miserable apartment. He finds grace in every circumstance (further explored here). Bernardos rips away the idealized, comfortable life we might daydream about. That line of thought that says, “If only I had some time of peace and quiet, maybe out in the country, with minimal confrontations, then I could really grow in my faith and relationship with God.” Sure, that would be nice and I wouldn’t pass that up. But God is so much bigger than that. Grace is everywhere.