![By Anonymous Russian icon painter (before 1917) Public domain image (according to PD-RusEmpire) owned by the Tretyakov Gallery [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/637/2016/05/DormitionIcon-250x300.jpg)

While it is true that the death of Mary, unlike her assumption, is not dogmatic, and so in theory one could believe in the assumption while remaining agnostic about her death, such a reading of the dogma does not understand the source and tradition which lies behind it, a tradition that included the death of Mary as the precondition for her assumption.[1] This is why it is beneficial for us to look at tradition and see how it related the two together. In doing so, we will find tradition did not believe that her death indicated any sin on her part, but rather, served a different purpose. For this reason, a glimpse into tradition will hopefully help Catholics and non-Catholics alike will better understand what was believed to have happened at the end of Mary’s temporal existence.

While a few early authorities follow St. Epiphanius and question whether or not Mary died, the majority had no problem in saying she died.[2] It is not just the number of sources, but the kinds of sources, and the authority which they hold, which is key: those who have had a far greater role in the development of our understanding of Christian doctrine are among those who have talked about her death, and they did so as if there was no question about her having died. For example, in what is like a summary of Mary’s life as a virgin, indicating the nobility of such virginity, Augustine wrote, “For being born of a mother who, although she conceived without being touched by man and always remained thus untouched, in virginity conceiving, in virginity bringing forth, in virginity dying, had nevertheless been espoused to a handicraftsman, He extinguished all the inflated pride of carnal nobility.”[3] Augustine, in verifying Mary’s perpetual virginity, indicated how she not only lived, but died, a virgin. Her perpetual virginity could be affirmed because her temporal existence had come to an end, while if it did not, then there would be room left to question whether or not she would remain a virgin forever. Moreover, Augustine had no question as to whether or not she died; it was assumed, which is why he thought that it could serve his argument.

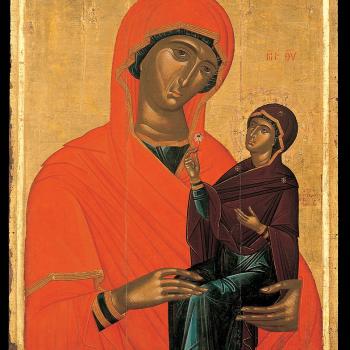

We can find many places in patristic literature similar ways of addressing Mary’s death like Augustine, where the author reflected upon Mary’s death as a given which they can use to make some other theological point. More important for us are those discussions which directly reflect upon her death as the central concern of the author, such as homilies which were written specifically to celebrate her death and assumption into heaven. The two were linked in the eyes of the faithful, so that they could be said, in the simplicity of John of Thessalonica, “When some time had gone by, this glorious virgin, the Mother of God, left earth by a natural death.”[4] Natural, yes, but also unique and special, so much so that the euphemism employed by St. Paul for death, sleep (dormition) was to be the normative way her death was described. For in her death, she went in peace, as if she had gone to rest, leaving her body with no corruption. In this way St. Andrew of Crete would find parallels with what happened to Adam in paradise:

Mary’s death was, we might say, parallel to that first sleep, which fell upon the first human being when his rib was removed to complete the creation of our race, and he received flesh to take the place of what had been taken away. In the same way, I think, she fell into a natural sleep and tasted death, but did not remain held by it; she simply followed the laws of nature and fulfilled God’s plan, which the Providence that guides all things laid down for us from the beginning.[5]

Likewise, St. Germanus of Constantinople proclaimed, Mary’s death was for her glory, because it led to her assumption, and not to her shame as sin would have made it:

In this way, when you had suffered the death of your passing nature, your home was changed to the imperishable dwelling of eternity, where God dwells; and becoming yourself his permanent guest. Mother of God, you will not be separated from his company.[6]

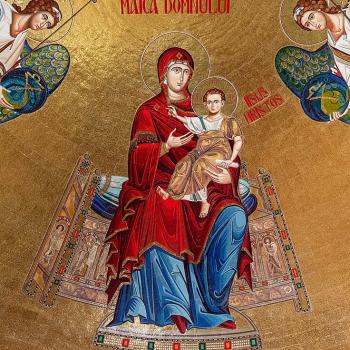

With many homilies like this, and other discussions on her death available, Blessed Jacobus de Voragine brought several texts together in order to establish the common medieval understanding of her death in The Golden Legend.[7] Fundamentally her death led to her assumption in the minds of the ancient writers, and this was shown in the way her death tended to be presented as a kind of special event witnessed by the Apostles. It is said that the Apostles were given a special indication that she was about to die, and so they came together to be with her and then to a funeral procession for her before putting her in a tomb. It was also said that three day after her death, her tomb was found to be empty, which then served to prove she had been taken into heaven by Jesus. This event, this coming together of the Apostles to honor Mary, is what commentators on Pseudo-Dionysius believe he indicated when he wrote:[8]

As you know, we and he and many of our holy brothers met together for a vision of that mortal body, that source of life, which bore God. James, the brother of God, was there. So too was Peter, that summit, that chief of those who speak of God. After the vision, all these hierarchs chose, each as he was able, to praise the omnipotent goodness of that divine frailty. But next to the sacred writers themselves was my teacher. He surpassed all the divinely rapt hierarchs, all the other sacred initiators.[9]

Other details would emerge as to how her death and funeral procession would be understood. For example, it was believed that a Jewish man, upon seeing the funeral taking place, tried to disrupt it by defiling Mary’s body. The attempt failed because an angel is said to have come down and cut off his hands; once he repented, and he became a believer they were then restored to him.[10] Theologically, this scene, often shown in icons of her funeral, connects to another Marian theme, which is to see Mary as the new Ark of the Covenant.[11] Her assumption into heaven is then the entrance of the true Ark of the Covenant into the Heavenly Temple (cf. Heb. 8:1-6). And just as during the time of Israel, the Ark of the Covenant was not to be touched, so it had poles placed on its sides which could be used to move it when necessary, likewise Mary was not to be defiled, and those who tried to do so would see God working against them.

More to Come

[1] To be sure, while the normative tradition is that Mary died, there are some, like St. Epiphanius, who were rather agnostic as to whether or not she died. See Luigi S.M. Gambero, Mary and the Fathers of the Church. trans. Thomas Buffer (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1999), 125-6.

[2] The texts are far too numerous to relate and so what we will offer here is but a sampling from them to demonstrate what kinds of thoughts were expressed in them.

[3] St. Augustine, “On the Catechizing of the Uninstructed” in NPNF1(3):307.

[4] John, Archbishop of Thessalonica, “The Dormition of Our Lady,” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 47.

[5] St. Andrew of Crete, “Homily II on the Dormition” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 121.

[6] St. Germanus of Constantinople, “Homily I On the Dormition” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 121.

[7] See Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend. Volume II. trans. William Granger Ryan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 89 – 97 for the section of the entry in which we find such a compilation, before which the author engages a discussion of the sources for the assumption, and the questions raised concerning some of them.

[8] We do not know who the author who called himself to be Dionysius actually was, but his works appear to come from the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 6th century. He wrote as if he were the first century convert, Dionysius the Areopagite, and so his writing on the death of Mary was written as if he had first-hand experience of the event. Despite such a ploy, his works are of vast theological importance, and, his thought holds a central place in the theological tradition. While some early readers questioned his value, he quickly became one which people from diverse theological traditions would quote and use for their own theological reflection. His testimony on the dormition was quoted by St. Andrew of Crete (circa 650 – 712) showing how quickly his writing would be used as representing the Christian tradition on Mary.

[9] Pseudo-Dionysius, “The Divine Names” in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. trans. Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 70.

[10] St. Germanus of Constantinople described the event in this fashion:

A certain foolish member of the unbelieving Jewish people – for they are a ‘vanity of vanities’ (Eccl. 1:2), always giving offense and always ready for a quarrelsome argument – reached out his lawless hand (for Scripture says, ‘In these hands there is always iniquity’ [Ps 25:2 (LXX)]), and shook the pallet that served as her bier, daring to molest the body of the immaculate one and not fearing even to throw to the ground the fleshly throne of the Most High. Immediately his hands were cut off, and he became a dreadful example to the Jews, who are always aggressive against Christ.

Germanus of Constantinople, “Homily II On the Dormition” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 176.

[11] The typology which sees Mary in the Ark of the Covenant would best be served by a contemplation on its own, but we shall mention in brief a few things here. The description of the Ark, what its function was, and its history all have parallels with Mary and her life. It was a chest which contained within it the tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments, Aaron’s Rod, and some of the Manna the Israelites received from God while wandering in the desert. The top of the Ark had two carved cherbubim on it, and between them was the “oracle”, the place where God’s presence was at (making it the visible throne of God). Mary had within her not the bread of angels (manna) but the bread of life (Jesus). Aaron’s rod, a wooden staff indicating his authority, was to have buds form on it, which Christian believe was a prophecy about the fruit of Mary’s womb, Jesus. Moreover, Jesus is the law incarnate, the Word, the Logos, revealer of the new covenant with its eternal law, so that by having him in her womb, there was also a parallel with the Ark holding the Ten Commandments within. Finally, Mary, who would have had Jesus on her lap, had become his throne, the place of God’s presence.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing