![By Anonymous Russian icon painter (before 1917) Public domain image (according to PD-RusEmpire) owned by the Tretyakov Gallery [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/637/2016/05/DormitionIcon-250x300.jpg)

The assumption of Mary, as we have seen, is tied to the ascension of Christ. The assumption is in many ways its completion. Since Jesus is the one who is the subject of the ascension, that is, since he is the one who ascended, this explains why Mary is said to be assumed into heaven. She is passive in relation to her entry into glory. But, as we said before, her assumption is not only tied to the ascension of Christ, but also to her own death. The assumption is seen to happen after her funeral procession and burial. Jesus is seen as coming to honor her in her death and the way that he does this is through her assumption, taking her soul and body to heaven upon which she is given her share in the resurrection of the dead.

It is for this reason we find the ancient celebration of Mary’s assumption was tied not only to the glory Jesus shown to her in the assumption, but also to Mary’s death. For it was understood that in completing her temporal existence with death, Mary was able to complete her life’s achievement and show in and through it why she was worthy of the highest earthly honor possible. She was seen as the greatest of the saints, and so when Scripture said, “Precious in the sight of the LORD is the death of his saints” (Ps.116:15 RSV), her death was to be understood as being the most precious to the Lord.

But, many ask, if she is so pure, if she is without sin, how could she die? Should she not be free from the curse of death? Yes, but that is why her death differs from the death of the rest of us. For those of us who sin, death is experienced as a curse, but for her, death was to be what God originally intended for humanity, the way which we were supposed to experience the end of temporal existence. It was, therefore, a means by which she was to go from glory to glory, from earthly honor to heavenly glory. At the end of our temporal existence, we die, our soul separates from the body and in that dissolution, sin takes over, leading us further with that dissolution towards the unbeing which is the foundation of sin. Mary did not experience death in this fashion – it was, for her, her entrance into eternal glory, the bridge which she had to pass through to go from temporal to eternal life. There was no sin in her, so there was no sin which could overtake her and lead her away from eternal glory, so that death, instead of being the means by which she could be lead further away from God was the means by which she was translated into eternal glory. We see in her, therefore, the fulfillment of God’s original intentions for humanity, showing that such intention is not just some speculative notion but rather, is a reality which was fulfilled in and through Mary.

That is, we see that the intention God had with us is that we would have experienced an end to our temporal existence; we were not expected to experience infinite time but rather to transcend time in eternity. There was always a role for death in human history. But the death which was brought about by sin was a spiritual death, and that death is the death which leads us to captivity in hell. Mary’s death was not a spiritual death; her death should not be seen as indicative of any taint of sin in her. And so there is no indication in her death of anything but glory. Her death takes her to glory, to her assumption, in which she is brought to eternal beatitude.

There is, moreover, another aspect of her death which we find maintained by early patristic homilies on her assumption. They say that she willingly entered death as a way to follow the example of her son, Jesus. It was an act of love where she made sure that she is not to be seen as greater than her son. That is, since Jesus is God incarnate, and he died, and indeed willingly experienced the sting of death, she did not want to give any appearance of being greater than her son, and so she followed him in and with the experience of death. Indeed, as usual with our understanding of Mary, what we see accomplished in and through her relates to what was done by her son, Jesus. If death is something which he willingly experienced, so she, likewise, is to find no shame in following Jesus into death. It is a part of the human condition to come to an end to our temporal existence, and so Jesus, in becoming man, took on that condition unto himself and his flesh; Mary, therefore, is able to share in and experience death with her son without any indication that she died as a result of sin. The tyranny of death, the sting of sin, was that the end of temporal life brought a spiritual death, but now, because of the death and resurrection of Christ, that sting is gone. In this fashion, St. Andrew of Crete preached of how and why death is no longer a curse:

It is death’s tyranny, real death, when we who die are not allowed to return to life again. But if we die and then live again after death – indeed, live a better life – then clearly it is not so much a death as a sleep (κοίμησις; “dormition”), a passage into a second life, which brings us as migrants from here to there and sends us on our way by giving us complete release from earthly cares. The author of the Proverbs expressed this more clearly than I when he said, “Death, for man, is rest”) (cf. Sir. 38:23). [1]

And so for Mary, who was assumed into heaven, her death literally was as if she went to sleep, which is why it is called her dormition. It was not a death of sin but the means by which she was taken into heaven and into eternal life. She willingly went into death so as to make sure that she was a proper and true follower of her son. If he went into death, so she, too, could do so and willingly. This is why St. John of Damascus said, “It was only right for that body to ‘lay aside what is mortal and put on immortality’ (1 Cor 15:53), since the Lord of nature himself did not refuse the test of death.”[2]

When Jesus died, he tore apart the necessary connection between death and sin, showing us that one who is without sin could die, just as those who sinned nonetheless could become purified from that sin and partake of spiritual rebirth and eternal life. Sin is no longer has power and control over human destiny; Jesus is Lord, not Hades. Death itself is no longer only associated with the sting and sin, but now it is also seen for its proper intention as the entryway into eternity. In this way, we do not have to see Mary’s death is indicative of any sin. She willingly engaged death itself, and allowed the end of her earthly existence to continue to be that of a normal human death; such a choice allowed the Apostles to come and honor her one last time in her funeral procession. Her love for God was so great that she willingly put her trust in God and followed her son on the path of glorification through death. If the death of a saint is precious, nothing is more precious than the death of Mary. It was not a death out of necessity but humble love: she freely decided to share in his death, so that she can share in his glory and presents to us a sign of the resurrection to come. We are all called, in our own way, to share in the death of Christ; this is exactly what happens to us in our baptism as well as when we “pick up the cross” (cf. Matt. 16:24) and follow him. Mary was able to do this in a unique way because of her special grace-filled character and disposition. She is the exemplification of what it means to be an imitator of Christ, which is exactly as we would expect, being her flesh was united with his. While we will experience death and resurrection through judgment, Mary, the pure lover of God, experienced it without qualification as the final exaltation of her love for God. St. Germanos of Constantinople expressed this well when he preached:

In this way, when you suffered the death of your passing nature, your home was changed to the imperishable dwellings of eternity, where God wells; and becoming yourself his permanent guest, Mother of God, you will not be separated from his company. For you become, in your body, the home where he came to rest, O Mother of God; and by your migration, O woman worthy of all praise, he is himself now the place of your repose. “For this,” he says, “is my place of rest for the ages of ages” (Ps 131:14 [LXX]): referring to the flesh which Christ took from you and put on himself, O Mother of God – the very flesh with which he not only appeared in this world and received faith in return, but with which he will also come again in the age to come, and will appear among us to judge the living and the dead. Because you, then, are his eternal place of rest, he has taken you to himself in his incorruption, wanting, one might say, to have you near to his words and near to his heart.[3]

To see Mary as not sharing in the common human destiny with death, therefore, is to be rejected. She is not outside of the normal human condition, rather she is its perfect representative. Sin corrupts nature and turns it away from its proper modality. Once we understand that, then we must understand that what is experienced in the death of a sinner is but a fallen mode of what God originally intended. With Mary we find that this intention was realized so that in and through her the original, integral nature of humanity has a place in human history. It is a real and not an artificial nature. If we do not believe this, we end up creating a new kind of docetism, where it is humanity as a whole which is illusory. But with Mary, we find that natural humanity is real, that it has a place in history, and she lived it, from birth to death, in perfection. To deny her death is to make sin not only a corrupter of human nature, but the creator of something new – and yet, by its nature, sin cannot create. Thus, in recognizing her death, we honor the original, integral human nature and God’s intention with it, including holy death that was meant to take all us from earth to heaven, from time to eternity. Death, in the end, can be seen to be a good, but only if it is the death of righteousness, while the death in sin, which we mostly know, is the curse which Jesus overcame.

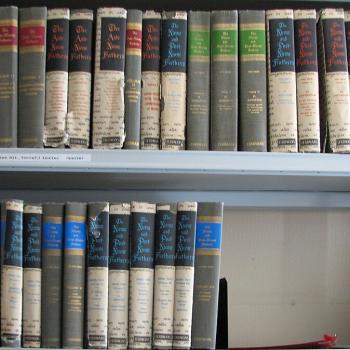

[1] St. Andrew of Crete, “Homily II on the Dormition” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 118-19.

[2] St John of Damascus, “Homily I on the Dormition,” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 194.

[3] St. Germanus of Constantinople, “Homily I On The Most Venerable Dormition Of The Holy Mother of God,” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 159.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing