But false prophets also arose among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you, who will secretly bring in destructive heresies, even denying the Master who bought them, bringing upon themselves swift destruction. And many will follow their licentiousness, and because of them the way of truth will be reviled (2Ptr. 2:1-2 RSV).

Unless we are careful, we will read Peter’s words anachronistically, interpreting the text with a later understanding of the word “heresy.” That is, we will read into the word heresy the technical meaning which developed, i.e., “doctrinal error held stubbornly in defiance of authority.”[1] Translating Peter’s words in this fashion has helped cause confusion to readers because they mostly will know and understand the later use of the term. Clearly, the translators understood its proper understanding because they translated the root word αἵρεσις differently when rendering into English Paul’s words in First Corinthians, “for there must be factions among you in order that those who are genuine among you may be recognized” (1. Cor. 11:19 RSV). What is rendered “factions” is the same word used by Peter, and indeed, this is why in many other translations of Paul’s text, the word is rendered as “heresies,” making for a consistent if not confusing translation.

The word “heresy,” when used in Scripture, should therefore not be read following the technical meaning which developed long after the Apostles. Rather, the word indicated a privately held opinion. The root word behind the noun αἵρεσις is the verb, αἱρέω, which means I choose or I prefer, and so when used as a noun, meant a personally established and held opinion or belief. Paul was saying there will always be people who develop factions based upon private opinion within the church, and through it, the truth will become known and realized. Peter was indicating that the promotion of private opinion over and above the common good will lead people astray, not only because it will lead people to deny truths of the revealed faith, but also because many will find ways to excuse or permit their various sins through such private opinion. Private opinion itself was not the problem, but “destructive” opinions, those which were held in contrast to the universal, common truth.

There certainly is a reason why the term “heresy” slowly developed into a technical, dogmatic term, because it was understood by the early Christians such privately held opinion when it was held against the common truth of the faith produced grave error and led people astray. Private opinion itself was understood as possible so long as it was not used to reject the public and universal truth established by the Apostles – after all, we all interpret what we hear and understand what we hear in such a way we establish private opinions based upon that understanding. Even privately held opinion which was erroneous was not necessarily heretical, in the technical sense, if the error did not contradict the public proclamation of faith, that is, if it could be held in unison with it. This is why St. Augustine was able to say not all errors leads to heresy, and why it is difficult to make a universal definition of heresy:

After all, not every error is a heresy; yet, since every heresy involves a defect, a heresy could only be a heresy by reason of some error. What it is, then, that makes one a heretic, in my opinion, either cannot at all, or can only with difficulty, be grasped in a definition in accord with the rules. [2]

We are limited in our knowledge and understanding. As we seek after truth, we will make mistakes. That is normal. Defining such mistakes was important, so that there could be a guide left behind to help people not fall for the same mistakes in the future. Many early texts against heresies were meant to be such guides, bringing together all kinds of erroneous opinions, such those beliefs found in Greek philosophy, with actual dogmatic error, such as found in various Gnostic circles (Cerinthus, Marcion, Valentinus, the Ophites, the Sethians, et., al.).[3] We would misunderstand these texts if we tried to read all discussion as indicative of dogmatic error because the pre-Christians could not be held as opposing dogma which had yet to be defined (though, if we follow them in errors which counter the truth of the faith, their private opinion could turn us into material and formal heretics).

It is normal for us to make mistakes, and so, for us to make various erroneous private opinions as we engage the truth. This is not itself a problem. The problem is found in the spirit in which we make our opinion. Do we think we know more than others, and our private opinions must be believed over and above all others, over and above the general and universal proclamation of the truth? When our ideas are examined, do we willingly let the universal and common truth overrule our private opinions, and acknowledge that there must be something missing from our understanding if our opinion contradicts the common truth? When we follow through with such humility, our errors, no matter how bad they are, are mere mistakes. It is when we begin to believe more in ourselves and our abilities and what we think we know over and above the public truth that we find our mistakes take on a new character, a destructive character, a prideful character which must be countered if we want to attain the truth.

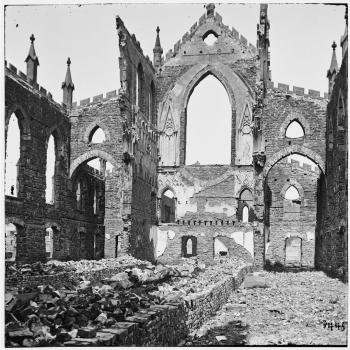

Humility requires us to understand our personal opinions are to be judged and criticized by the universally established truth. When our thoughts and beliefs are shown to be defective, we must put our private opinion aside. But when we do not, then we have taken on the spirit of heresy. Like all heretics, we promote ourselves as having superior knowledge to the commonly established and proven truth, to be gnostics, while we are ignorant and in reality, agnostic in regards to the truth. The spirit of heresy is the spirit of pride, which confuses conventions for absolutes and so cuts off the truth from its fullness as the absolute no longer remains absolute. It blurs things, so truth and falsehood look like.

Error, as St. Irenaeus explained, easily disguises itself as the truth because it takes some aspects of the truth and hides itself in that partial truth: “Error, indeed, is never set forth in its naked deformity, lest, being thus exposed, it should at once be detected. But it is craftily decked out in an attractive dress, so as, by its outward form, to make it appear to the inexperienced (ridiculous as the expression may seem) more true than the truth itself.”[4] The convention used by heresy will often appear similar to other presentations of truth, it will take on and use elements of the truth, but the private opinion with its interpretation has emptied the contents of the truth to mere opinion. Its exterior hides from the casual observer and investigation the corruption which has taken place, but an examination of what is believed will reveal its hollow nature. As individualism cuts people away from each other, from the common good, so private opinion, when left unchecked, cuts away from the truth, leaving it in pieces and incapable of being found among any of them.

This is why we must not rely upon ourselves, thinking we are, in and of ourselves, to be the upholders of the truth. We hold private opinions, and no matter how good they are, they are in need of the fullness of truth which is found outside of ourselves, of the truth guided by the Holy Spirit in the church as a whole.

St. Epiphanius once wrote, “For every heresy deceives, not having received the Holy Spirit according to the tradition of the Fathers in the holy catholic church of God.”[5] He is right insofar as every private opinion which holds itself apart from the common and universal faith cuts itself off from the Holy Spirit and the pillar and ground of the truth, so that no matter how great the idea that is presented when it is taken from and cut away from the fullness of the truth, it will collapse in and of itself. Tradition shows the work of the Holy Spirit in protecting the common truth from the unholy spirit of prideful opinion and its disintegration of the common good. This is why St. Irenaeus was able to say that the heretics, those who promoted private opinion as some superior truth, had to be criticized in relation to the one universal faith:

But, again, when we refer them to that tradition which originates from the apostles, [and] which is preserved by means of the succession of presbyters in the Churches, they object to tradition, saying that they themselves are wiser not merely than the presbyters, but even than the apostles, because they have discovered the unadulterated truth.[6]

Tradition helps keep private opinion in check. Tradition points out that no matter how wise and smart we are, whatever we will understand is going to be limited and the universal truth will transcend us. We need each other to complement each other so we can properly present that universal faith. If we think we can do it alone, we will fail. The spirit of heresy is that pride, that individualism, which seeks to bring us away from each other and trumpet ourselves above the rest. That spirit, while it has always run rampant throughout history, is especially present today, as modern society is based upon the spirit of individualism over the common good. We find it ever present on the internet, where such division is especially common, as factions fight each other over their private opinions, instead of uniting together in love.

The spirit of heresy is alive and well all around us. It is present in our lives, always tempting us to follow it. Let us turn away from, it, fight it at every turn, confess when we fail to do so, less we shall find its destructive nature affecting us, destroying us within and without, leaving us in confusion and despair.

[1] Walter L. Wakefield and Austin P. Evans, trans. and intr., Heresies of the High Medieval Ages (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 2.

[2] St. Augustine, Heresies in Arianism and Other Heresies. intr. and trans. Roland J. Teske, S.J.. ed. John E. Rotelle, O.S.A. (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 1995),33.

[3] Even as late as in the writings of St. John of Damascus do we find this mixed- use of the word heresy being employed when demonstrating the various possible heresies which he knew and understood.

[4] St. Irenaeus, Against Heresies in ANF(1):315.

[5] St. Epiphanius of Cyprus, Ancoratus. trans. Young Richard Kim (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2014), 149.

[6] St. Irenaeus, Against Heresies in ANF(1):415.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing