St. Gregory the Wonderworker, whose feast is November 17, was, as his name suggests, known for a life filled with great miracles. But, as it is clear in his biography written by St. Gregory of Nyssa, this was because he was a man of humble virtue. He did not seek glory for himself. He avoided the priesthood, seeking instead a quiet life of solitude, and yet, bishop Phaidimos of Amaseia found a way to meet with St. Gregory the Wonderworker in person and overcame Gregory’s opposition to being ordained a priest. Later, as a bishop, he would show his heart’s passion was to continue to live up to the expectations of virtue, similar to the way virtue was said to be attained by Lao Tzu:

St. Gregory the Wonderworker, whose feast is November 17, was, as his name suggests, known for a life filled with great miracles. But, as it is clear in his biography written by St. Gregory of Nyssa, this was because he was a man of humble virtue. He did not seek glory for himself. He avoided the priesthood, seeking instead a quiet life of solitude, and yet, bishop Phaidimos of Amaseia found a way to meet with St. Gregory the Wonderworker in person and overcame Gregory’s opposition to being ordained a priest. Later, as a bishop, he would show his heart’s passion was to continue to live up to the expectations of virtue, similar to the way virtue was said to be attained by Lao Tzu:

A man of the highest virtue does not keep to virtue and that is why he has virtue. A man of the lowest virtue never strays from virtue and that is why he is without virtue. The former never acts yet leaves nothing undone. A man of the highest benevolence acts, but from no ulterior motive. A man of the highest rectitude acts, but from ulterior motive. [1]

Those who seek after virtue and hold onto it for some ulterior motive, such as fame or glory, have lost something virtue in themselves and so are defiled by pride. Such impurity in motive denigrates whatever good they have achieved; they might be of the highest rectitude, but the true magnificence of virtue is not something which they have attained because of their internal disposition.

Those who hold true virtue act without question for the sake of the good, never considering or deliberating between the good and bad: virtue is natural for them, while those who have yet to attain such natural goodness stray from virtue; they might will some good, but it will be a lesser good which they have deliberated and established for themselves. It might help open them up and prepare them for true virtue, but so long as they keep to their opinion of the good instead of finding a way to will the good beyond deliberation, they will falter from the fullness of virtue. Ulterior motives, conscious or not, will likewise affect their deliberation, so that if they have yet to be overcome, they will also lead those who seek the true good to falter away from it and hold on to and seize for themselves some lesser good.

The pursuit of virtue should not be confused with the pursuit of knowledge of good and evil. Human knowledge will always be imperfect, for it will not be able to comprehend the fullness of the good. Only one is good, only one comprehends the fullness of the good, and that is God. To try to comprehend the good is it misunderstand it; one who thinks they comprehend the good will have less of it than their potential would allow. Virtue, and the holiness which it entails, is a state of being, what is established naturally in a person. One can have accumulated great theoretical knowledge and deliberate what is good as a result of it, but this deliberation will only lead so far before it has to be transcended by an act of the will. Likewise, if the knowledge does not lead to action, then the person certainly cannot be said to be virtuous – indeed, the more they knew and fall away from what they know, the worse they end up being. It is how one acts, and the grace which allows one to attain good habits for oneself which establishes true virtue. For this reason, St. Gregory the Wonderworker said that he learned from Origen that the true education is not for the accumulation of facts, but for the training of the student so they will act properly and not just become a possessor of vain knowledge:

He did not teach us how to act by standard definitions such as “prudence is knowledge about good and evil or about what to do and what not to do”; indeed, [he taught us] that this kind of learning is vain and unprofitable, if the word by supported by works, and if prudence does not do what is to be done and avoid what is not to be done, but simply provides its possessors with knowledge of these things, like many people we see. [2]

Accumulating knowledge of what is good is merely theory until it becomes lived out. A good student is to be trained to act in prudence, to act in wisdom, and not just repeat and recite what others have said and done in the past. The best student will have transcended mere theory and actually tapped into what goodness they have in themselves and work with it, help it grow, so that with grace, they can truly come to act without thought and therefore, without any ulterior motive which such thoughts could bring.

While Christianity recognize the natural good inherent in humanity, it also teaches that we have lost contact and sight of that goodness due to sin. Likewise, it is also weakened; the potential which we have is lost to us. We are, in a way, half-alive, and so at half-strength, even in our virtue. It is in this light God the Word is shown to be in the world, helping to bring us back to life, protecting us from those things we would do which would entirely destroy the goodness which we still have. Teachers, therefore, work as instruments of the Word. St. Gregory recognized that Origen acted like a guardian to his youth, helping work with the Word to spiritually heal him and prepare him for his own walk with God. Uncertain of where God would take him, Gregory said to Origen:

There is the Word, the Savior of all, who protects and heals all those half-dead and robbed, the unsleeping guardian of all human beings. And we have seeds, those which you showed us that we already had, and those we received from you, the good thoughts. With these we depart, weeping as we go, but still carrying these seeds with us. So perhaps the guardian who attends us will preserve us; perhaps we shall return to you again, bearing the fruits and the sheaves produced by the seeds – not perfect (how could they be?), but such that we can produce from the affairs of city life, weakened by some sterile or malevolent force, but not entirely without value for us, if God approves. [3]

But, as we live in the world, as we strive for virtue and do not yet have it, we must keep in natural law; it teaches us general principles, showing us what acts are grave evils which we must avoid, lest they strangle the good seed which remain with us, leaving us even more wounded than before. As these good seeds are the foundations for our future beatitude if we water them and let them grow in grace, we must protect them by eliminating our own bad habits, from the rocky soil of pride, hatred, and avarice, weeds which will strangle and destroy the good seed if we let them develop without contention. Christians in an age which promotes greed and those who attain great wealth as being good must contend against society and denounce the evil which they promote. When capitalism is taken as an ethic, then the love of money is seen as good. Greed, however, must be far from the Christian life. From the very beginning the Christian faith has taken a harsh stand against greed, and it cannot relent on this now; indeed, St. Gregory the Wonderworker banished those who stole from the poor out of avarice from the church:

Greed is terrible, and it would take more than one letter to list the holy Scriptures where not only robbery is denounced as horrible and to be shunned, but all greed and seizing others’ possessions out of base covetousness. And everyone of this kind is publicly banished from the Church of God.

If we want to be followers of Christ, then, we must come to terms with all that is good in the world and bring it unto ourselves, producing good fruit; but we must not let evil defile us. We must do more than pursue the question of ethics; we must live it out. Certainly, as we are far off from the good, we can explore conventional morality, raise questions and help figure out some basic parameters by which we should live. But we must do more than that. We must transcend such conventions. We cannot keep hold of such ethics, pursuing them with rigid legalism. Only when we receive the spirit of the good and let it penetrate us and lead us in our will shall we be able to attain it, for we will find we are not the possessors of virtue but the ones who have become possessed by it. And that is what being a saint entails: the light of virtue shines through them and penetrates their whole being so that nothing has been left undone.

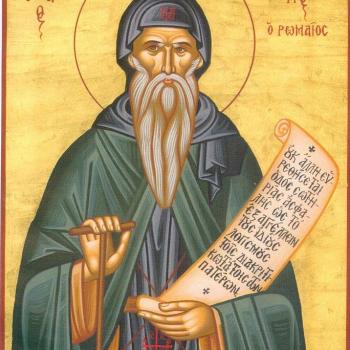

[Image= St. Gregory the Wonderworker By Anonymous [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching. trans. D.C. Lau (London: Penguin Books, 1963). 45.

[2] St. Gregory Thaumaturgus, “Address of Thanksgiving to Origen” in St. Gregory Thaumaturgus: Life and Works. trans. Michael Slusser (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1998), 111.

[3] St. Gregory Thaumaturgus, “Address of Thanksgiving to Origen,” 125-6.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook