Jesus told his disciples that he was going to go and prepare a place for them, a place in his Father’s house, that is, in the eternal kingdom of God. They did not understand. Thomas, speaking up, asked not only where Jesus was going, but how to get there, to which Jesus answered:

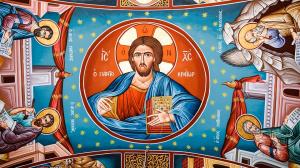

I am the way, and the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father, but by me. If you had known me, you would have known my Father also; henceforth you know him and have seen him (Jn. 14:6b-7 RSV).

Jesus pointed out that not only was he the way, so that in and through him, we would be able to enter into the kingdom of God, he was the way because he was also the truth. Those who want to encounter God, the absolute truth, find it in Jesus. The way is the truth, and truth is the way. The way to what? To the truth.

How can this be? Is this not circular reasoning? The truth is the way to the truth? And if we already embrace the truth, does this mean we embrace Christ and find our way to the Father? Philip wondering about what Jesus meant, asked Jesus to show him the Father, to which Jesus replied:

Have I been with you so long, and yet you do not know me, Philip? He who has seen me has seen the Father; how can you say, `Show us the Father’? Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father in me? The words that I say to you I do not speak on my own authority; but the Father who dwells in me does his works. Believe me that I am in the Father and the Father in me; or else believe me for the sake of the works themselves (Jn. 14:9b-11 RSV).

Jesus is the way to the truth because he is the truth. He is the truth as it reveals itself to us. The absolute transcendent truth is not only transcendent, but immanent; and it is not just a generalized immanence in which we find the presence of truth everywhere, it has become particularized in the incarnation. If we encounter Christ, we come face to face not only with him, but with the Father. He is one with the Father. The Father is in him and he is in the Father: the Son is eternally begotten of the Father, and in his divine nature, never separated from the Father. Where the Son is, the Father is also present, because the two, though distinct, are never divided from each other. The Son is the Son of the Father, the express image of the Father, God from God, truth from truth. The truth, the absolute truth, is with us in Jesus.

We encounter the absolute truth in Jesus, yet, when we receive that truth, we receive it in a form in which we can comprehend. The Word of God, the Logos, assumed human nature and shows us truth in a human form. The absolute truth is revealed to us in a form which truly presents to us the truth while remaining transcendent: it becomes incarnate, it becomes thick, as St. Maximus the Confessor explained, as it empties itself for us of its absolute incomprehensibility so that in its immanence, we receive a representation of the truth which is true because it remains one with the absolute:

Or one could say that the Logos “becomes thick” in the sense that for our sake He ineffably concealed Himself in the logoi of beings, and is obliquely signified in proportion to each visible things, as if through certain letters, being whole in whole things while simultaneously remaining utterly complete and fully present, whole, and without diminishment in each particular thing. [1]

The Logos, the Son, has become one of us, so that the absolute truth condescends to reveal itself to us in a form which is appropriate to our needs and capabilities while remaining at the same time the absolute truth. The Logos empties himself and reveals himself, the eschaton lives within time while remaining eternal and the foundation for all time. The two natures of the Son, divine and human, demonstrate the two forms of truth, one which is incomprehensible and transcendent, and the other which is apprehensible and immanent, revealing that they are one so that by realizing and coming to know the apprehensible relative truth, we can then know the absolute truth which is one with it.

But we must come to Jesus with a proper desire for the truth. We might naturally desire the truth, and this is good, but as Hugh of St Victor warned us, we must come to it with the right intention:

The desire to know the true good belongs to the soul and is naturally implanted in every soul. But although every rational soul naturally desires this, yet it is often deceived in discerning how it ought to desire the truth. Indeed, to desire the truth incorrectly is to desire it with curiosity or cupidity or iniquity.[2]

When we are overly curious, or seek to know some element of the truth for selfish gain, we pretend to care about the truth, but in reality, we do not; we want to use the truth and abuse it, instead of letting it reveal itself to us in the form best suited for us. Being overly curious is a problem because it demonstrates the lack of wisdom: the desire to eat of the tree of knowledge of good and evil came out of such curiosity, with a desire to know something, evil, which should not be known because the only way to know it is in the destruction of the good. We become easily swayed by our desire to know partial truths as if that means we desire the truth, and so we end up cutting up the truth and dissecting it, unable to know it from its parts and unable to put it back together so long as our treatment of it is so unholistic. The truth confronts us as one whole: the truth comes to us, and reveals itself to us in a form which we can apprehend, in a conventional truth which represents and is penetrated by the absolute, but our curiosity seeks to cut the two apart, and to establish through pride, new notions of truth which can contain elements of the truth but is dead because they no longer are penetrated by the absolute truth. We must have the two together, as one, if we want the truth, and that means, we must accept the form in which the truth reveals itself to us, in the form which we are most capable of receiving. Even Jesus, in his human form, presenting the relative truth did so in a way which allowed the absolute to determine the contours of that presentation, which is why he said, “I do not speak on my own authority,” meaning that the human, relative presentation of the truth can never be the truth on its own but can only come from and be presented as the truth in and through the absolute and how the absolute judges and determines the conventions by which the truth is to be revealed.

Origen, therefore, explained that we are called to have the contemplation of God, the absolute truth, as our sole activity, and we will do so in and through the Word, that is, Jesus:

For at that time those who have come to God because of the Word which is with him will have the contemplation of God as their only activity, that, having been accurately formed in the knowledge of the Father, they may all thus become a son, since now the Son alone has known the Father.[3]

In this way we become one with the son of God, Jesus, so that we can be led to the Father and contemplate and receive the truth, both in a conventional form which we can apprehend, and in its transcendence because the absolute truth dwells with and is found within the conventional form of the truth. This is a part of the transformation which the Word, the Logos, the Son, intends for us, the way in which the truth is the way for us to enter into the eschatological kingdom and receive the truth: through the conventional, relative truth, we are led to the absolute truth which already lies within. Jesus is the way, for in and through our encounter with him in the flesh, in the conventional forms of the truth which we apprehend, we are then led beyond ourselves, beyond the flesh, beyond all conventions and into the absolute itself, where we shall dwell in eternity. But as St. Maximus also indicated, we must remember that ascent is possible in the Word because the Word became flesh and emptied himself, without change, so as to reveal the truth to us:

And to disclose a greater secret about these things: whosoever is able to be lifted up from the knowledge concerning the dispensation, that is, from the Word’s world of flesh made by the Father, to the intellection of the glory of the Word’s flesh with the Father before the world was made, has truly ascended into the heavens together with God the Word, who for his sake descended to earth. Such a man has reached the limit of knowledge that human beings can contain in this present age, for he has become God to the degree that God became man, for man has been guided by God, through the stages of divine ascent, into the highest regions, to the same degree that God has descended down to the fathers reaches of our nature, emptying Himself without change.[4]

Jesus truly is the way, the truth and the life, the way in which the truth reveals the truth to us, and the way of truth which we must follow if we want to receive the truth, and enter into the many mansions of the Father, that is, for us to enjoy the bounty of the absolute truth itself.

[1] Saint Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua. Volume II. Trans. Nicholas Constas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 63 [Amb. 33].

[2] Hugh of St Victor, “Sentences on Divinity” in Victorine Texts in Translation: Trinity and Creation. Trans. Christopher Evans. Ed. Boyd Taylor Coolman and Dale M. Coulter (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 2011), 113.

[3] Origen, Commentary on the Gospel According to John Books 1 – 10. Trans. Ronald E. Heine (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1989), 52.

[4] Saint Maximos the Confessor, On Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua. Volume II, 265 [Amb. 60].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook