Source: unknown photographer /pxhere

Early Christians, writing with the vigor of a newfound faith which had yet to deal with the messy issue of being a faith that extended through long periods of history, looked upon the great moral improvements promoted by Christians as representing the superiority of the Christian faith to other religions.[1] Christians worked together, lived together, suffered and died together, showed their love for one another – as well as for their persecutors.[2] It is easy to see how and why early Christian apologetics contained many triumphalistic representations of the faith, claiming the moral superiority of Christians to pagan and Jews alike. Christian writers, looking at the horrors of the past, could claim “we are different,” which in a way, was true at the time, but would quickly become false as Christianity formed a history of its own, a history which tied it to the nations of the world.

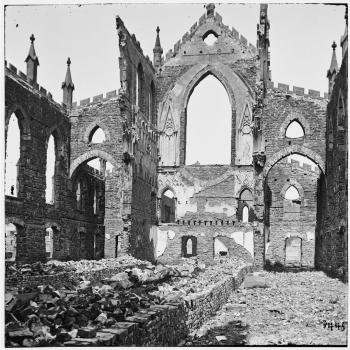

Early Christian writings about the superiority of Christians to their counterparts based upon the upstanding character of Christians themselves can not be repeated today without laughter: anyone who knows the history of the Christian faith will realize Christian history is, like any other form of human history, riddled with all kinds of scandals which cannot easily be dismissed. Christians have tied themselves to the world. This itself was not wrong, for they had to reject any Gnostic denunciation of the world, but in doing so, they have allowed themselves to take in the problems of the word. Instead of taking such problems in to transform the world and perfect it, Christianity has slowly found itself darkened by such contact, with leader after leader, Christian after Christian, shown to be capable of being not only corrupt, but morally reprehensible in the policies and actions which they have enforced.

Christians need to honestly reflect upon their own history and accept that, despite the graces offered to the Christian faith, Christian history is a history of Christian failure to follow such grace and properly integrate it into world history. This is not to say God failed, that Christ failed. Christians are the ones who failed as they failed to live out the dictates of Christ. In the midst of all the darkness and filth of Christian history, it is true, one can find the true teachings of Christ being stated and used to encourage reform so that the salt of the earth, though covered often in mire, can still be found. But because such mire has grown so as to hide the good, a triumphalistic picture of Christian history should no longer be preached: the teachings of Christ, the greatness of what he taught and preached and what he expects of us, should continue to be promoted, but Christians need to be honest with themselves in how they have failed to follow Christ. Christian history is riddled with diabolical leaders who have hindered the mission of the Gospel.[3]

Christians, having now had their own history, filled with good and bad exemplars of the faith, can and should look to the history of the Jews, not as something by which they can contrast themselves with and look upon themselves as being superior, but rather, as something which reminds them of how God continues to work with and promote good people and saints in the midst of imperfect, corrupt societies. The people of Israel, the good, faithful people of Israel, suffered constantly at the hands of corrupt leaders: God did not lose sight of his desires, and he helped such people despite the corruption of the priestly and kingly institutions, sending prophets to speak not only on his own behalf but on behalf of the ordinary people of Israel as well. The story of Israel is the story of humanity, the story of how human institutions centered around the grace of God, will continue to be penetrated by grace despite whatever corruption, whatever inhumane injustice can be found around it. Christian history, now with hindsight, can be seen to be no different. Christian history parallels the history of Israel: God’s faithfulness to the people of Israel remained even though their leaders were not so faithful: the same must be said about the history of God with the Christian people. God remains faithful: he continues to give out his grace, his saving and deifying graces, in and through the means he established (though not limited to them), so that those who want to follow him can have the means to do so, no matter who is in charge of the institutional church. Christians who see evil around them should not despair of the grace of God; likewise, they should not think it is something extraordinary or rare so as to suggest it is proof that the literal end of time is near as if it means we are near the final confrontation between the Gospel of Christ and the anti-Christian opposition to Christ.

Those who know Christian history should not be surprised about any and every abuse they find in contemporary Christian circles. Those who do not, however, are rightfully surprised and discouraged, especially if they have been given a false triumphalistic expectation for the institutional church. Many converts, like early Christians, expect the church to reflect their own newness of faith, and if they have been given apologetic material which reifies those expectations, there is no surprise how and why such converts could quickly lose their faith, because they will think what they were told was mere lies. Christians need to be honest with their imperfections, and the imperfections of Christian institutions, so that then they will be ready to deal with those imperfections when they find them. Sexual abuse in the church is not new, just as the political corruption of church institutions is not new. To try to reduce these crises through ideologies is to ignore the real problem and the reforms which are needed: there will never be one over-arching solution, as there is no one over-arching cause for corruption. Reductionistic ideologies will only create worse evils in the future because they will ignore the dangers and risks which are not in accord with their ideological filter.

Vladimir Solovyov reminds us that the true Christian faith is one of regeneration, where the grace of God catches us and transforms us. We find the grace within a social context, and we interpret it through the teachings of the Christian faith. These are all necessary, but they are not and should not be our focus:

True and unfeigned Christianity is neither dogma nor hierarchy, neither church service nor morality, but the quickening spirit of Christ, actually, even if invisibly present in humanity and acting in and through complex processes of spiritual development and growth – a spirit embodied in religious but not exhausted by these forms, not brought about definitively in any given fact. Traditional institutions, forms and formulas are necessary for Christian humanity, as a skeleton is necessary for a higher order of living organism, but in and of itself a skeleton does not constitute a living body. A higher organism can not live without bones, but when the arty walls or heart valves begin to ossify, then this is truly a symptom of inevitable death.[4]

The people of Israel found spiritual transformation and regeneration was possible as God’s grace was shared to them through the Mosaic Covenant. Whatever corruption was found in the leadership of Israel, the simple people of Israel could and find God’s faithfulness was still with them, indeed, pleading for them in and through the prophets who consistently challenged the corruption of priests and kings alike. The prophets spoke with the pathos of God, out of the love God had for the oppressed. The priestly institution, even when ran by corrupt officials, remained in place and continued to be a source of grace for the people of Israel. Israel was blessed by the religious rites in the Temple, though when the hearts were not pure, the prophets would point out the uselessness of such rites in and of themselves. This is why through the prophets, God saw the harm done by the corruption seen in the institutions of power and authority in Israel and worked on behalf of the people to challenge and reform those institutions through the prophets and providential events in the history of Israel (with the destruction of the Temple and the Babylonian Exile being one of the most extraordinary means of such an interplay between God, history, and the correction of the people of Israel).

Christians should consider the history of Israel and know that being chosen by God means God will require the same correction of their institutions as God expected of the institutions of Israel. God will send prophets to challenge those institutions when they do not follow God’s desire for them, and in the end, he will treat them as he did the institutions of Israel if and when they will not reform. This does not mean they will end, nor that the people who rely upon them to receive grace will fail to receive grace from them. God will keep his promises and will work in and through them. But those in positions of authority in these institutions should consider themselves warned of the consequences of taking such power for themselves while failing to live out the expectations of such authority. The ordinary Christian can and should look to the institution for sacramental graces, and the preservation of the basic teachings of the faith necessary to hold up the faith throughout history, but they do not, and should not do so in a triumphalistic fashion, thinking Christian history will be any different from the history of Israel. People will be people; sinners will be sinners, and those seeking positions of authority for their own private gain will continue until the end of time (even as in the figures of Judas and Simon Magus, they were in and with the church from its foundation). Christians should engage the institution for what it is worth; they can even reflect on the significance of the institution and its good, but then they should do more, to live a life of faith for themselves, to let the Christian faith regenerate them, and if need be, to challenge authorities when such authorities no longer give an authentic witness of Christ and his teaching on love (in a fashion, of course, worthy of a Christian which respects the institution even when the people in positions of authority do not). Christians should not be surprised that sinners exist in the church, nor that they hold positions of power: as the history of Israel shows us, this should be expected. They should avoid all apologetics which would suggest otherwise. Then Christians will be ready to accept the institution of the church for what it is, and not for what it is not, hoping or expecting more from it than it being the skeleton which holds up the Christian faith so that it can continue on from generation to generation. Nonetheless, as Solvoyov suggests, an authentic Christian life will then move beyond a focus on the institution and its doctrines but on a living faith. Our focus should be on Christ, putting on Christ and living out our lives as being lives in Christ. The church, its leadership, and its doctrinal teachings cannot be ignored, but they must also be seen for what they are, and not more than that.

[1] Without doubt, Christians did revitalize Rome with its notions of social justice and sin. Christians were able to institute new social programs in society which helped the underclass, such as the establishment of hospitals which gave free health care to those who needed it, to food distribution to the poor. Roman society changed as a result of this, and we find pagans, like Julian the Apostate, trying to continue with these changes, though without the spirit of Christian charity, the programs faltered.

[2] Their willingness not only to forgive but to promote those who once persecuted them came out of their devotion to the teachings of Christ found in the Sermon on the Mount. They truly wished good will for their persecutors: they rejoiced when their former enemies joined their community. With caution, they even allowed many of their adversaries enter into the church to become leaders of the church itself.

[3] This should not be read so as to deny God was and is able to work in and through such leaders: he can, and does, so that the spiritual charism found in the church continue. God can and does use bad leaders, “bad vessels,” so that contrary to any Donatist inclination, recognizing the wickedness of Christian leaders should not be used to reject the way God uses them despite their evil to spread his graces to those who seek after them. God will not hurt honest, loving, people by removing such graces from the world,

[4] Vladimir Soloviev, “On Counterfeits” in Freedom, Faith, and Dogma. Trans. Vladimir Wozniuk (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2008), 148.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook