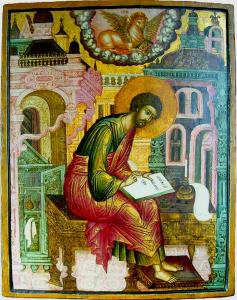

Scripture tells us little concerning the writer of the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles. Luke gives us a few glimpses as to why he wrote his texts, but we are given next to nothing concerning his own particular biography. We might try to connect him to the companion of Paul mentioned in the book of Colossians, “Luke the beloved physician and Demas greet you” (Col. 4:14 RSV), Philemon (cf. 1:24), and 2 Timothy (cf. 4:11), but it is only with outside tradition, from historical sources outside of Scripture, do we have the warrant to connect the two. If we accept non-scriptural sources, which we should since Scripture is best interpreted from that context, then we can have a better understanding of who Luke was, and accept that he was indeed the companion to Paul who was an educated physician. Eusebius and Jerome, both historians with sources which do no longer possess, give us the kind of basic biographical information which we are interested in. Eusebius, therefore, wrote:

But Luke, who was of Antiochian parentage and a physician by profession, and who was especially intimate with Paul and well acquainted with the rest of the apostles, has left us, in two inspired books, proofs of that spiritual healing art which he learned from them. One of these books is the Gospel, which he testifies that he wrote as those who were from the beginning eyewitnesses and ministers of the word delivered unto him, all of whom, as he says, he followed accurately from the first. The other book is the Acts of the Apostles which he composed not from the accounts of others, but from what he had seen himself.[1]

Jerome, likewise, affirmed Luke was Antiochian by birth, a physician by profession, but also suggested that Luke wrote his Gospel, in part, through his association with Paul and what he learned from Paul, although it is likely this comes from an over-literal understanding of Paul when he talks about “his gospel.”[2] It should not be a surprise that Luke had Paul as one of his sources, because he was a coworker with Paul. Nonetheless it is believed that other Apostles, and Mary herself, also spoke with him and helped give him the special insight which is found in his Gospel alone. Thus, Eusebius explained:

But as for Luke, in the beginning of his Gospel, he states himself the reasons which led him to write it. He states that since many others had more rashly undertaken to compose a narrative of the events of which he had acquired perfect knowledge, he himself, feeling the necessity of freeing us from their uncertain opinions, delivered in his own Gospel an accurate account of those events in regard to which he had learned the full truth, being aided by his intimacy and his stay with Paul and by his acquaintance with the rest of the apostles. [3]

What is missing out from these accounts of Eusebius and Jerome are other traditions which suggest Luke was perhaps one of the seventy disciples sent out by Jesus; that it, they do not suggest the possibility that Luke was a follower of Jesus long before Paul’s conversion.[4] This does not mean he did not learn from Paul, nor that he did not interview other apostles and Mary, but if this were true, it would suggest that he included some of his own personal experiences into his narrative.

It is important is to realize that the Apostle Luke was one of the most Hellenized authors of the New Testament. His training as a physician made him one of the most educated Apostles. It is apparent that he did not give up his profession in order to work with Paul. Luke remained a physician, helping people heal in body even as he and Paul worked together to spread the Gospel and provide spiritual healing to those who would come to them and listen. Marsilio Ficino, therefore, could and did look at St. Luke as an example as to someone he could follow, demonstrating that physicians and priests not only share common concerns, but that there was something appropriate with someone being both – as well as being someone interested in Hellenism and the great depths of learning which was available to those who studied it.[5]

Anyone who would oppose Christian engagement with secular learning, or who would promote some sort of cult approach to healing that looks only to faith healing without consideration to what normal medical practices can do to help people, find themselves standing in stark contrast to the Apostle Luke. Once we recognize the Hellenistic background of Luke, his interests in the Acts of the Apostles, showing many times in which the early Christian community opened itself up to accept Gentiles, as well as to Hellenized Jews like himself, makes perfect sense (cf. Acts 6:1-7; 10:1-48; 15: 1- 35; 17:22-31).[6] Indeed, it would seem that Luke found Paul to be a very accommodating figure in this regard, which is probably why he found himself interested in making Paul a central figure in his history of the early church.

Luke, then, is a prime example of Christian possibilities. As a physician, though he would have been suspicious with some magical techniques promoted by various cultic shrines, he would still have had an interest in and possibly used many methods which today would look suspiciously close to magic. But, because we do not know much about his practice, we can only speculate as to what it was like based upon contemporary accounts of medicine in his time. As a disciple of Christ, and later an Apostle and a writer of the Gospels, he showed us that Christians can and should embrace secular learning, to engage history itself. The Christian faith is very worldly. Luke, in his writings, makes sure the Christian faith remains rooted not only to God, but to the world at large. Thus, he showed us how the early church, from its inception, reached out to the culture at large, learned from it, and was able to adapt itself to it, in order to present the faith to others.[7] When we turn to the writings of Luke today, if we forget this, we forget one of the many lessons which we can and should learn from Luke himself, a lesson which is important for us today as we see Christians struggling to understand how to reach people in a variety of cultural forms today.

[1] Eusebius, Church History in NPNF2(1):136-7.

[2] Thus, we read:

Luke a physician of Antioch, as his writings indicate, was not unskilled in the Greek language. An adherent of the apostle Paul, and companion of all his journeying, he wrote a Gospel, concerning which the same Paul says, “We send with him a brother whose praise in the gospel is among all the churches” and to the Colossians “Luke the beloved physician salutes you,” and to Timothy “Luke only is with me.” He also wrote another excellent volume to which he prefixed the title Acts of the Apostles, a history which extends to the second year of Paul’s sojourn at Rome, that is to the fourth year of Nero, from which we learn that the book was composed in that same city. Therefore the Acts of Paul and Thecla and all the fable about the lion baptized by him we reckon among the apocryphal writings, for how is it possible that the inseparable companion of the apostle in his other affairs, alone should have been ignorant of this thing. Moreover Tertullian who lived near those times, mentions a certain presbyter in Asia, an adherent of the apostle Paul, who was convicted by John of having been the author of the book, and who, confessing that he did this for love of Paul, resigned his office of presbyter. Some suppose that whenever Paul in his epistle says “according to my gospel” he means the book of Luke and that Luke not only was taught the gospel history by the apostle Paul who was not with the Lord in the flesh, but also by other apostles. This he too at the beginning of his work declares, saying “Even as they delivered unto us, which from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word.” So he wrote the gospel as he had heard it, but composed the Acts of the Apostles as he himself had seen. He was buried at Constantinople to which city, in the twentieth year of Constantius, his bones together with the remains of Andrew the apostle were transferred — St. Jerome, Lives of Illustrious Men in NPNF2(3): 363-4.

[3] Eusebius, Church History, 153-4.

[4] See, for example, the dubious text attributed to Hippolytus, “On the Seventy Apostles” in ANF(5):255. This would also explain why Lk. 10:1-12 is traditionally read on his feast day, since it would be a narrative from his own Gospel concerning an event which he participated in.

[5] See Marsilio Ficino, “The Apology of Marsilio Ficino” in Book of Life. Trans. Charles Boer (Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications, 1996), 187.

[6] Saying he was a Hellenist is not to say he wasn’t a Jew, but rather, to suggest he was a Hellenized Jew. Of course, it is fair to say, most Jews in the first century were Hellenized to some extent, as Martin Hengel in his many works often demonstrates. Nonetheless, being a physician, he would have had wider contact with secular culture and learning than many others, which is reflected in his literary style and interests.

[7] Legends suggest some of the earliest paintings of Mary were also done by Luke. While some might dismiss such beliefs as being unfounded, as many icons attributed to Luke seem to date from an era in which he did not live, it is not inconceivable that there was a ground of truth to this tradition. And if there are, it would have been another example of Luke’s adaptation of the faith, using what he learned from his Hellenistic background to produce such paintings for the faithful, applying Hellenistic notions of portraiture to the faith.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!