One of the great powers of symbols is that they are quite adaptable; the same symbol can be used to represent multiple meanings. Often, the meanings evolve, one from another, adding layer after layer of meaning. This means that previous understandings of the image are included in and help explain their new meaning once the transformation has taken place.

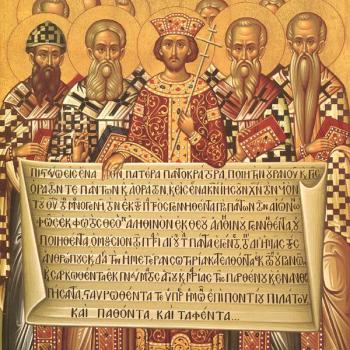

Christians, since the foundation of the Christian faith, have taken symbols from the culture around them, using the meaning already associated with various images to help in the construction of their new, Christian signification. Christian images – whether they are painted, like icons, or carved into statues – did not come about ex nihilo. Those who know how to read Christian art know the symbols employed and their meaning; they can understand what it is saying to its audience. Someone from a different culture, someone who does not understand the symbols, might appreciate elements of the art and accept what it is said to represent, but unless they take time to study the symbols employed and what they meant to the original audience, they will lose much of the significance of the work in question. Worse yet, those who think their culture should dominate others, that is, those who look down upon and frown upon other cultures and their images, will denigrate and degrade the meaning given to symbols coming from different cultures; Christians who do so tend to make the claim that the image is “pagan” and worthy of being destroyed. In doing so, they reiterate the mistake of the iconoclasts, but now, with history repeating itself, their actions indicate the establishment of a farce.

Christians, to be sure, have a history of trying to understand the relationship between their faith and the culture at large. When ancient Christians found themselves gaining power and authority in ancient Rome, Christians and non-Christian “pagans” often fought each other, sometimes destroying each other’s holy sites. Nonetheless, the assimilating power of Christ made sure, even in the tragedy of such violence, Christians did not entirely destroy the cultural legacies of the past; instead, Christians took over and embraced the symbols of their non-Christian peers, making them relate their pre-Christian meaning with the Christian faith. This is exactly what we see happen with the destruction of the Serapeum of Alexandria.

Theophilus, the Patriarch of Alexandria, was a triumphalist. “In the Coptic tradition, Theophilus is remembered as a champion of the struggle against paganism.”[1] As the historical details differ according to the people telling it, it is hard to know who exactly started the riots in Alexandria, but what is clear, Theophilus took advantage of them to have soldiers and monks destroy various pagan sites, the most famous being the Serapeum, dedicated to Serapis. ”The fall of the Serapeum was one of the more notable events of the end of the fourth century, remarked by both Christian and pagan authors.” [2] While historians think the accounts tend to be overly simplified, taking many separate events and turning them into one large narrative, the general story is that various pagans ran into the Serapeum, trying to hide there, after which the soldiers, and various Christians, came over and took possession of the Serapeum:

At the solicitation of Theophilus bishop of Alexandria the emperor issued an order at this time for the demolition of the heathen temples in that city; commanding also that it should be put in execution under the direction of Theophilus. Seizing this opportunity, Theophilus exerted himself to the utmost to expose the pagan mysteries to contempt. And to begin with, he caused the Mithreum to be cleaned out, and exhibited to public view the tokens of its bloody mysteries. Then he destroyed the Serapeum, and the bloody rights of the Mithreum he publicly caricatured; the Serapeum also he showed full of extravagant superstitions, and he had the phalli of Priapus carried through the midst of the forum.[3]

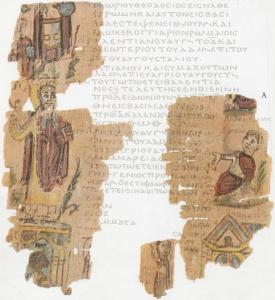

What is interesting is the description of what was found in the Serapeum: images of the ankh. Thus, Sozomen wrote:

It is said that when the temple was being demolished, some stones were found, on which were hieroglyphic characters in the form of a cross, which on being submitted to the inspection of the learned, were interpreted as signifying the life to come.[4]

Likewise, Socrates informs us:

When the Temple of Serapis was torn down and laid bare, there were found in it, engraven on stones, certain characters which they call hieroglyphics, having the forms of crosses. Both the Christians and pagans on seeing them, appropriated and applied them to their respective religions: for the Christians who affirm that the cross is the sign of Christ’s saving passion, claimed this character as peculiarly theirs; but the pagans alleged that it might appertain to Christ and Serapis in common; ‘for,’ said they, ‘it symbolizes one thing to Christians and another to heathens.’ Whilst this point was controverted among them, some of the heathen converts to Christianity, who were conversant with these hieroglyphic characters, interpreted the form of a cross and said that it signifies ‘Life to come.’ This the Christians exultingly laid hold of, as decidedly favorable to their religion. But after other hieroglyphics had been deciphered containing a prediction that ‘When the cross should appear,’— for this was ‘life to come,’— ‘the Temple of Serapis would be destroyed,’ a very great number of the pagans embraced Christianity, and confessing their sins, were baptized.[5]

Socrates, doubtful that there was such a prophecy, he accepted that divine providence could have been behind the establishment of the ankh so that it could later be used by Christians to promote the Christian faith similar to the way Paul was able to accommodate his teaching to those on Mars Hill:

Such are the reports I have heard respecting the discovery of this symbol in form of a cross. But I cannot imagine that the Egyptian priests foreknew the things concerning Christ, when they engraved the figure of a cross. For if ‘the advent’ of our Saviour into the world ‘was a mystery hid from ages and from generations,’ as the apostle declares; and if the devil himself, the prince of wickedness, knew nothing of it, his ministers, the Egyptian priests, are likely to have been still more ignorant of the matter; but Providence doubtless purposed that in the enquiry concerning this character, there should something take place analogous to what happened heretofore at the preaching of Paul. For he, made wise by the Divine Spirit, employed a similar method in relation to the Athenians, and brought over many of them to the faith, when on reading the inscription on one of their altars, he accommodated and applied it to his own discourse. Unless indeed any one should say, that the Word of God wrought in the Egyptian priests, as it did on Balaam and Caiaphas; for these men uttered prophecies of good things in spite of themselves. This will suffice on the subject.[6]

The ankh was the ancient Egyptian symbol for life. Christians, seeing it, saw it as a representation of the vindication of Christ, for it was an image which looked like the cross. Since by the cross, Christ gives us life, so the ankh, they believed, represented the victory of Christ, not only in giving us life, but also over paganism as a whole. Thus, they had no probably appropriating the image for themselves. Ann M. Nicgorski used this as a key example of the way images were used and transformed in ancient Roman Egypt:

This episode is a wonderful example of a type of semantic progression that is typical in the heterogeneous religious and cultural context of late Roman Egypt. [The ankh, the ancient Egyptian sign of life, inscribed] on architectural elements from the Serapeum, was now recognized as a fluid, multivalent symbol of “the life to come,” understood and accepted by diverse, and even opposing, cultural groups. The traditional ankh was then transformed into the new crux ansata, a looped cross with a more circular (rather than tear-shaped) head, which became a potent symbol of the early Christian Church in Egypt that represented Christ’s sacrifice and the promise of salvation while still testifying to the continuity of ancient Egyptian tradition.[7]

The ankh turned into the crux ansata in ancient Egypt. Christians employed ancient Egyptian symbols, borrowing from their original meaning but adding to them, establishing their own Christian application for such images. Christians knew of their non-Christian origins. Non-Christians still employed them and spoke of their meaning. This is exactly what happened with the ankh. Christians adapted it to represent the victory of Christ, not only in the victory of life over death, but also of the rise of Christianity in the ancient world as a whole. Egyptian Christians had no problem borrowing from and using their own cultural legacy and applying it to the Christian faith. This is what Christians have always done. This is exactly what Christians in the Amazon Region have done with Our Lady of the Amazon. With Our Lady of the Amazon, traditional symbols representing motherhood and fertility are raised up and use to establish an image of Mary, the Mother of all Christians, whose fertility brought forth the Lord of Life. Those who would decry the indigenous using their own symbols in establishing Christian representations must decry the whole development of Christian images as a whole, since Christian images have always borrowed from the culture in which they developed. This is why images of Christ as Orpheus can be found in the catacombs and used to established frescoes: Christians knew the underlying symbolism and meaning of Orpheus and saw it them a meaning which can then be taken over and employed by the Christian faith.[8] Egyptians Christians taking over the ankh for the sake of the establishment of the crux ansata is another representation of this tradition, where there was even more acknowledgment of the relationship between the ancient symbol and its Christian adaptation. Our Lady of the Amazon is just a modern representation of this great Christian tradition. Those who decry the image, those who attack it and applaud its destruction, follow the example of the ancient iconoclasts who rejected the authoritative teachings and traditions of the church in regards the use of images. For if no non-Christian images can ever be transformed into a Christian one, then no image will be possible as all images can be traced to non-Christian sources. The triumph of Christianity, represented by Theophilus, therefore includes the ability of Christians to take from and engage pagan symbols, transforming them, transfiguring them, based upon their original meaning to a full Christian representation. Those who believe otherwise do not seem to believe Christ has triumphed; they do not believe he is Lord over all the earth.

[1] Norman Russell, Theophilus of Alexandria (London: Routledge, 2007), 7.

[2] Norman Russell, Theophilus of Alexandria, 7.

[3] Socrates, “Ecclesiastical History” in NPNF2(2):126.

[4] Sozomen, “Ecclesiastical History” in NPNF2(2): 386.

[5] Socrates, “Ecclesiastical History,” 126-27.

[6] Socrates, “Ecclesiastical History” in NPNF2(2):127.

[7] Ann M. Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis: A Paradigm for Transformations in the Culture and Art of Late Roman Egypt,” in Roman in the Provinces: Art on the Periphery of Empire. Ed. L. Brody and G. Hoffman (Chestnut Hill, MA: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College, 2014), 155.

[8] Images of Zeus also are another source for images of Christ: “This transformation and continuity of tradition from the Hellenistic to the late Roman and early Christian period is also apparent in one of the earliest known icons of Christ from Sinai, dating to the first half of the sixth century CE […], an image that clearly derives its authority from its evocation of the ‘Zeus/Jupiter facial type,’ which was shared by the Greco-Roman Serapis,” Ann M. Nicgorski, “The Fate of Serapis,” 155.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!