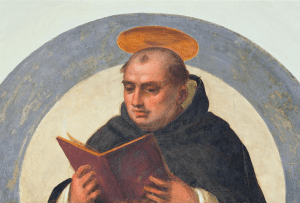

St. Thomas Aquinas pointed out there is a distinction between what we can come to know about God through the use of reason, and what we can know about God through revelation. Revelation transcends what we can come to know about God through reason, and so those who follow revelation will know more about God than those who have not the use of such revelation. However, by saying this, it becomes clear that it is one and the same God being discussed through reason and through revelation, and not some other God, despite the distinctions between reason and revelation, and the greater depth of knowledge one can have through revelation. If someone’s belief about God does not contain all that is contained in revelation, or even if they believe something about God which is later contradicted by revelation, they cannot be said to be believing in a different God from the God of revelation. God remains God, whether it is God as understood and discussed by the philosophers, or it is God as understood and discussed by those who have received the fullness of revelation in and through Jesus Christ.

Thus, St. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Contra Gentiles, explained:

Some truths about God exceed all ability of the human reason. Such is the truth that God is triune. But there are some truths which the natural reason is also able to reach. Such are that God exists, that He is one, and the like. In fact, such truths about God have been proved demonstratively by the philosophers, guided by the light of natural reason. [1]

If the philosophers, who did not know the fullness of revelation (and so did not know about the Trinity), are said to know truths about God, such that he exists and is one, then it is clear, they know about God and it is the one and only God which they know. Their lack of knowledge of the Trinity does not make their belief in God be about a different God than those who believe in the Trinity. They hold and believe in truths about God. It is not necessary to believe in the Trinity to believe in God and that God exists. Indeed, Aquinas reiterated throughout his writings, philosophy and reason alone could not attain to the teaching of the Trinity (in its proper form); no argument, without revelation, can suffice to prove the Trinitarian nature of God as being necessary for God:

That God is both threefold and one is solely an object of belief. There is no way of proving it demonstratively, though some arguments can be given in its favor which are not necessarily convincing nor very probably, except to the believer. [2]

Aquinas, therefore, had no problem looking to those of other faiths, of those who did not have the revelation of the Christian faith, and see in them people who believed in God, albeit with an imperfect, incomplete, and often error-ridden understanding of God. They believe God exists. Their belief is correct, and it is established through reason. “Regarding the unity of the divine essence, we must first believe that God exists. This is a truth clearly known by reason. “[3] Revelation is important not only to teach us about the truths of God which are impossible for us to ascertain on our own, it also helps us so that we do not have to rely upon our fallible mental abilities to reason out basic truths of God. For even if we can discern reasons to believe in God, those reasons can be difficult to establish, and not everyone will be able to attain the level of competence needed in order to discern God through the use of reason alone.

Likewise, if reason alone cannot be used to prove the faith, Aquinas also thought it cannot be used to disprove the faith:

There is one matter about which I want to advise you, namely, when you dispute with unbelievers about the articles of faith, you should not try to prove the faith with necessary reasons, for such a procedure would deprive the faith of its sublime quality, the truth of which not only transcends human minds, but angelic as well. These, in fact, are believed by us as revealed by God. Because whatever proceeds from the Supreme Truth cannot be false, nor can anything necessarily true be used successfully to attack what is false, our faith cannot be proven by necessary reasons. Neither, moreover, can it be disproved by necessary reasons, and this is precisely because of its truth.[4]

Reason’s limitations are the limitations of the human mind. Reason cannot offer a-priori evidence, it can only offer conclusions based upon what is given to it, that is, to foundations which transcend reason itself. Reason cannot prove or disprove the faith, because there is always some level of faith before reason is employed, some sort of belief which serves as the foundation for reason’s arguments and conclusions. Thus, those who think they can and will only believe what they discern through reason are being dishonest with themselves. They have faith in the premises which they bring to reason. And this is why Aquinas could say that those who think we should only believe what they can discover by reason are liable to err: “Second, one may err because in matters of faith he makes reason precede faith, instead of faith precede reason, as when someone is willing to believe only what he discovers by reason.”[5] For the error lies in the presumption that anyone can use reason all by itself. We all begin with some matter of faith which we then use to reason out our beliefs. Aquinas showed us that once we recognize this, then we come to understand the need for outside revelation to teach us and lead us with the proper foundation by which we can use reason to reach a greater understanding of the truth:

There are some truths, however, which do not come within the range of these principles, like the truths of faith, which transcend the faculty of reason, also future contingents and other matters of this sort. The human mind cannot know these without being divinely illumined by a new light supplementing the natural light. [6]

But if this so, how can he say that reason provides us the grounds for belief in God? Because God reveals himself in and through his effects,[7] which we can then use to discern that he must exist, and then from his existence, to some basic knowledge about him and his transcendence:

Therefore through natural reason we can know about God only what we grasp of him from the relation his effects bear to him, for example, attributes that designate his causality and transcendence over his effects, and that deny him the imperfection of his effects. [8]

This distinction between what philosophy can discern about God through natural revelation (the use of what we can discern about God as we use reason to engage our senses to learn truths about reality), and what we can know about him through his active self-revelation (through prophets, but especially through the incarnation), Aquinas said created two different branches of theology:

Accordingly, there are two kinds of theology or divine science. There is one that treats of divine things, not as the subject of science but as the principles of the subject. This is the kind of theology pursued by the philosophers and that is also called metaphysics. There is another theology, however, that investigates divine things for their own sakes as the subject of the science. This is the theology taught in Sacred Scripture. [9]

Once again, it is important to note the distinction here concerns what we know about God, and how we discuss what we know, but it is not about the creation of distinct Gods. Those who know God only through the light of natural revelation (philosophy) are not said to believe in a different God from those who follow revelation. Those who come to believe in God believe in the same God with those who believe in God as he reveals himself in revelation. Muslims, therefore, believe in the same God as Christians. This is why their arguments for belief in God refer to the true God and can be used by Christians. Aquinas confirmed this many times in his use of Muslim thinkers and what they said about God, such as when he said they believed in the God who governed the universe:

Damascene proposes another argument for the same conclusion taken from the government of the world. Averroes likewise hints at it. The argument runs thus. Contrary and discordant things cannot, always or for the most part, be parts of one order except under someone’s government, which enables all and each to tend to a definite end. But in the world we find that things of diverse natures come together under one order, and this not rarely or by chance, but always or for the most part. There must therefore be some being by whose providence the world is governed. This we call God. [10]

The problem is not that Muslims, or heretics, believe in a different God, it is that they err in their conceptions about God. Muslims, Aquinas said, did not truly appreciate the depth of the mystery of God, and so in their lesser realization of God, they mocked the Christian faith: “From a similar mental blindness, Muslims are led to ridicule as well the Christian Faith which confesses Christ, the Son of God, died, because they do not grasp the depth of so great a mystery.”[11] But, they cannot be said to be wrong about God if they believed in and were teaching about a different God. This is why Aquinas, in discussing the errors of the Islamic faith, could and also grouped them along with Christians whom he believed were wrong about God (such as the Greeks in their rejection of the filioque). Thus, Aquinas did not argue that differing, indeed, erring beliefs meant people believed in different Gods, but rather because they are talking about the same God, we can talk about such errors.

St. Thomas Aquinas, in his talk about God, helps us realize how and why the church can and must teach many people, Christian and non-Christian alike, believe in the same God despite their differences in belief.[12] For when we can show agreement on the level of natural theology and the basic truths of God, we are clearly talking about the one and same God. What we do not know outside of revelation does not lead us to believe in different Gods once revelation is given, rather, it allows us to receive greater knowledge and understanding about God. Thus, those who come to believe in one God over all, be they Platonists, Aristotelians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Native Americans, Christians, et. al., they can all come together in their belief in the one God. They are grounded together in God despite the differences of their faiths. Likewise, Aquinas showed we can therefore learn from those of other faiths in regards their basic arguments and premises for belief in God, and perhaps what they discern from that belief, even as we are to use what we learn from revelation to supplement and transcend what we learn from natural theology. Indeed, it is what he thought we should be doing, and so he, in his work, made it clear it was how he would pursue the truth of God when talking to the diversity of the nations of the world: “We shall therefore proceed to set forth the arguments by which both philosophers and Catholic teachers have proved that God exists.” [13] If the philosophers, who did not know the Trinity, could and did believe in God, and we can learn from them how to discuss God, it is clear that this is how Christians can and should engage others, from other faiths, realizing of course that what is lacking must be supplemented with the fullness of Christian revelation.

[1] St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles. Book One: God. Trans. Anton C. Pegis (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 1975), 63.

[2] St. Thomas Aquinas, Faith, Reason and Theology. Trans. Armand Maurer (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1987), 31.

[3] St. Thomas Aquinas, Light of Faith: The Compendium of Theology. Trans. Cyril Vollert (New York: Book of the Month Club, 1993), 9.

[4] St. Thomas Aquinas, On Reasons for Our Faith Against the Muslims, Greeks, and Armenians. Trans. Peter Damian Fehlner (New Bedford, MA: Franciscans of the Immaculate, 2002), 22.

[5] St. Thomas Aquinas, Faith, Reason and Theology, 38.

[6] St. Thomas Aquinas, Faith, Reason and Theology, 17.

[7] “It remains that God is known only through the form of his effect,” St. Thomas Aquinas, Faith, Reason and Theology, 21. And this offers a way for us to connect Aquinas to St. Gregory Palamas, whose discussion of the uncreated energies of God, are all about discerning God through his actions (and so, through his effects).

[8] St. Thomas Aquinas, Faith, Reason and Theology, 32.

[9] St. Thomas Aquinas, The Division and Methods of the Sciences. Trans. Armand Maurer (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 1986). 52.

[10] St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles. Book One: God. Trans. Anton C. Pegis (Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 1975), 96.

[11] St. Thomas Aquinas, On Reasons for Our Faith Against the Muslims, Greeks, and Armenians, 32.

[12] Thus, Nostra Aetate finds precedence in the work of Aquinas.

[13] St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles. Book One: God, 85.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!