Early in Christian history, especially during the time before Constantine, Christians often engaged and recognized truths found in various pagan religions, their prophets, and the philosophers who emerged from those religious traditions (the division of philosophy and theology into two separate and distinct disciplines is a much later development). We find this especially established by various apologists (like St. Justin Martyr and Eusebius), who pointed out how God could be said to have inspired elements from these other religious traditions so that people from those traditions were prepared for the incarnation. They said that these inspirations, and the truths contained in them, pointed to the absolute truth which would be revealed in Christ, and in this fashion. Christ could be said to be the one who fulfilled all human expectations, even those found in the various religious traditions found throughout the world. They embraced what St. Paul said on Mars Hill: that most religious traditions acknowledged an unknown, transcendent God, and that in doing so, they already acknowledged the God of the Christians. What has change is that in and through the incarnation (and the work of the Holy Spirit), that unknown, transcendent God has also been revealed to us in an immanent way, a way which we can apprehend and learn more about God than what we ever could have done before. That is, the incarnation gives us the ultimate revelation of God, but it is a revelation which is founded upon and embraces all other revelation which God had given to humanity throughout the centuries, bringing them all together into a comprehensive, integral whole.

One way many Christians acknowledged the inspiration of God within pagan religious traditions was to say they had been given philosophers to help lead and direct them in a way similar to the Jews had been given prophets. They did think this meant all traditions were equal, as they were not, nor did they think it meant the inspiration always came to us in a pure form, as they recognize that after the inspiration was given, humanity and its sin often came to use and abuse the little they have been given, undermining the best elements of the human tradition. Nonetheless, no matter how corrupted those traditions had become, they still had in them elements which pointed to and directed us to the truth of God, and so, elements, thanks to the inspiration (and grace contained in that inspiration) capable of working for the salvation of humanity.

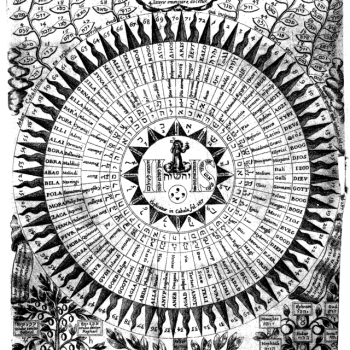

During the Renaissance, we see this early Christian notion being picked up and engaged in a way early Christians could and did not do so, that is, with a freedom to explore the various religious and philosophical traditions of humanity, with an eye out to see what brought them together or how they can be seen as preparing us for the ultimate truth in Christ. This is because Christianity had been able to present itself and its teachings and no longer felt itself holding a defensive position which required it to be as critical of non-Christian tradition. Many came suggest that there was a perennial tradition (philosophy or religion) which could be found throughout the world, a tradition which Christianity takes up and complements and completes, making it possible, in a way, to say all these religions are representations of one religious tradition or faith, presented in a variety of cultural forms (albeit it, also, with various levels of corruption as well). Marsilio Ficino, representing this line of thought, said that God provided everyone with holy mysteries and, through them, those who loved what is good and true continued to seek after and attain some element of both in their lives:

The eternal wisdom of God determined that the divine mysteries, at least at the very beginnings of religion, are only to be handled by those who are the true lovers of the true wisdom. Therefore, it happened that among ancient men, the same men investigated the cause of things and diligently conducted sacrifices to the highest cause of things itself, and the same were themselves also philosophers and priests among all the nations.[1]

Ficino, likewise, pointed out, throughout all such traditions, when they were inspired by God, will show that inspiration by the way they will embrace love, as love inspires and sustains religion: “Indeed, creation is so ordered that there is no true love that is not religious, nor is there any true religion but that sustained by love.”[2]

The ancient Christian engagement of other religious traditions not only was picked up during the Renaissance, but it has also been taken up in modern times as represented by Vatican II Nostra Aetate, and serves as the foundation for the way Pope Francis sees God is at work with major religious traditions, allowing them to serve as paths to God. Seeing them as paths to God must not be used to deny the distinctions between religions, nor to suggest that all religions are equal, but rather, it is the realization that God is always at work with humanity, in all cultures and societies, and that work is often manifested in the various religions which have emerged in human history. What Christianity has always suggested is that there is a way to connect all those forms of inspiration, to show how they come together and culminate with the revelation of God in Christ. The God-man is the one who bridges heaven and earth, God and creation, providing the grace needed for the salvation of the world, not just those who came after him, but also those who came before him and believed and acted on the inspiration they had been given.

Once we appreciate that the Holy Spirit has been abroad, inspiring people around the world (and, of course, their religious traditions), Christians will find they are free to explore other religious traditions, study what they teach, see the sparks of inspiration in them and use what they learn to better understand the Christian faith itself. Fr. George Maloney, for example, said we can understand the sacraments, such as confession, better once we see how other religious traditions found ways to have people repent and be forgiven of their offenses (be it some sort of sacrifice, or, in some later traditions, like Buddhism, some kind of confession and works of penance to better oneself). Humanity has always understood that people can err, do some wrong which needs correcting, and that for that correction to take, people who err will have to acknowledge their faults and seek to do better, often pleading to the divine realm for help:

People of every religion and culture feel a basic need to be reconciled with God after committing sins against their conscience or against the established taboos of society. They delt with this need through repentance and, in many groups, through some form of confession of their guilt and shame accompanied by an offering of expiation and sacrifice to the Supreme Being, their Creator.[3]

In the incarnation, all that was good and true in the human condition, including its religious traditions, were taken up by Christ, who helped preserve and fulfill the good which came before instead of seeking to recreate humanity by destroying all that came before him and starting over ex nihilo:

By studying some of the common elements found in the rituals and practices of non-Christian religions, we can understand more clearly what Jesus teaches us in the Sacrament of Reconciliation. He came not to destroy, but to make perfect what the Holy Spirit had begun before the Word of God became flesh and dwelt among us.[4]

To be sure, the sacrament of reconciliation, confession, is all about this; it shows us that grace perfects nature, that what has been corrupted or hurt by sin is not annihilated by God but rather taken up by God, who frees it from all defilement, and makes it better, greater, with grace. Thus, however corrupted we are by sin, God will find something good in us to use for our own spiritual healing, and this is what God can be said to do also with the religious traditions throughout the world. No matter how corrupted they might have become over time (which, of course, also includes historical Christianity), there is some good in them, some good which God will use for the betterment of all humanity.

Those who believe all non-Christian religions are completely and absolutely corrupt, having no truth in them, having no form of inspiration contained in their history, possess a faulty understanding of God, one which ends up suggesting God is at work with only small (and perhaps, predestined) groups of people instead of the whole of humanity. They do not believe God truly works for or desires the salvation of the whole world. This impoverished understanding of God leads to all kinds of bad ideas which get further reflected in their beliefs and practices. They end up thinking that anyone who is not in that small elect group is unworthy of our consideration, unworthy of our love, and possesses nothing good in them, which is why God will abandon them and so should we. They usually claim only those who are Christian have the potential of being in that small remnant which God will save, so that those who are not Christians, have nothing which Christians can and should accept, so that, if Christians are seen engaging ways similar to such non-Christians, it is evidence of the corruption of Christianity, of something which needs to be eliminated from the Christian tradition. Not only does this lead to a very impoverished form of Christianity, the more this line of thought is embraced, the more Christians will end up denying many truths because those truths are found in non-Christian traditions, until, at last, the whole of Christianity will have to be denied because there will always be something which relates to what is believed to some non-Christian tradition. That is, the only logical conclusion of this line of thought is atheism, as non-Christians believe in God, believe in supernatural grace, believe in the after-life, believe in all kinds of things which would have to be denied. Agostino Steuco, seeing this, believed he must, in some fashion, defend the general religious tradition (the perennial philosophy) from those, especially Protestants of his era, who wanted to purify Christianity from paganism by denying anything which has a pagan connection; he suggested Christians either defended the general religious tradition of humanity, or one became an atheist. Sadly, this important insight was lost over time and Christians for quite some time have taken on the rigid, puritan-like stand against non-Christian tradition; it is not surprising, therefore, that modern atheism emerged during this era, as many who became atheists took seriously what they had been told, and they pursued it out of a desire to follow what is good and true, only to find the logical conclusion of that line of thought is atheism (and many, likewise, found the abuses coming from religion only strengthened their resolve and served as a confirmation that they were right in rejecting religion).

Christianity is able to be inclusive in its approach to other religions, recognizing that no one has been left outside of God’s embrace. This is not to say all religions are equal, that all of them apprehend the same portion or quality or even quantity of the truth. To say all religions have been inspired by God, and that all of them have elements of grace, says only that; how much, and how those elements of truth and grace are to be coordinated and work together, are concerns which emerge only after we recognize God’s inspiration and grace permeating the world and its religious traditions. And, just as we can see Christians often diverting from the truth given to them, so that Christianity is always in need of reform, we should not be surprised this is true for all other religious traditions – this is why, if and when some element of those traditions can be shown to be erroneous, we do not have to deny the whole tradition, but rather, we should do as Fr. Maloney suggested, which is to find the good which remains, pick it up, learn from it, and use it to better our own relationship with God. What we should not do is seek to annihilate that which has been corrupted, for when we do that, we do not follow the way of God, but of sin, for that is the ultimate aim of sin, that of the annihilation of all that is good.

[1] Marsilio Ficino, On the Christian Religion. Trans. Dan Attrell, Brett Bartlett, and David Prreca (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022), 47.

[2] Marsilio Ficino, The Letters of Marsilio Ficino. Volume 1. trans. by members of the Language Department of the School of Economic Science, London (London: Shepheard-Walwyn, 1975; repr. 1988), 92 [Letter 48 to Filippo Controni of Luccai].

[3] George A. Maloney, SJ, Your Sins Are Forgiven: Rediscovering the Sacrament of Reconciliation (New York: Alba House, 1994), 16.

[4] George A. Maloney, SJ, Your Sins Are Forgiven: Rediscovering the Sacrament of Reconciliation, 16.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.`