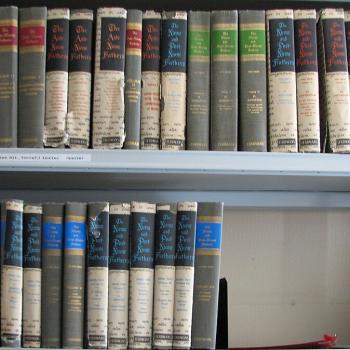

Studying and learning from patristic writers can be very rewarding for the Christian, but they must make sure they do so with care. They should realize, as Abelard and others would point out, patristic authors often had divergent theological opinions, and they often manifested that disagreement in very uncharitable forms. While on particular issues, we might find, as it were, a patristic consensus, to do so often requires reading authors coming from different context, using different forms of vocabulary, and so, it requires work on our part to find that consensus. At other times, no such consensus will be found, and we will have to decide for ourselves which author, if any, has the best opinion on a particular subject. We must realize that even if they are saints, even if they have been gifted with great charisms, they were still human. Their faults must also be taken into consideration when we study them. This is why we should not feel guilty if we end up criticizing them, so long as our criticism is justified and does not dismiss what was good and true in what they said and did. Sadly, as the Orthodox theologian Nikolaos Loudovikos explained, many readers are unable to do this; they feel that troubled if they have to criticize something they read from a man or woman known to be a holy saint. But, as Loudovikos stated, an unwillingness to criticize them can be as dangerous as ignoring them:

They almost feel guilty when a critical filtering of the written ecclesiastical tradition is required of them. They identify the holiness of the Fathers with the holiness, omniscience, and fullness of God Himself, and essentially idolize them, becoming unable to discern the “treasure in earth vessels” (2 Cor. 4.7). The fact that the Father are saints – and they really are saints! – does not mean that they do not complement and correct each other, that they do not have human failings or – on account of such failings – human faults and one-sidedness, as Abba Barsanouphios observed (Barsanouphios and John, Questions and Answers 604). Treating the Fathers, or Christian Hellenism, as idols, instead of engaging them in a living and crucially existential manner, leads to an equally dangerous pit for contemporary theology as was the centuries-long ignorance of them. [1]

Patristic writers are important because, as Jean Daniélou indicated, they represent a witness of the faith of the early church, helping us see the way the faith continues to be the same as it was in the earliest eras of the church, even if it was discussed and explored through a different cultural background:

We are to look for it in the Fathers of the Church inasmuch as they are a witness of the faith of primitive Christianity. In them, we see this biblical theology as refracted through a Greek mentality, but this mentality affects only the method of presentation. The fact that the Good Shepherd appeared dressed as Orpheus does not alter the fact that it is He Whom Ezechiel announced, and Whom St. John showed us as actually having come in the person of Christ. [2]

Thus, there is much value in reading patristics but we must be cautious in doing so. We must not treat them as being more authoritative than they are; in their own time, they were often like us, struggling to explore and discuss the faith to the best of their abilities. They might have had special experiences, some which are connected to the fact that they lived so close to the beginning of Christian history, but we have the same Spirit directing and guiding us today as they had in theirs. That Spirit will make sure that the faith can and will be taught in a way which best meets the needs of the day, even as it helped Christians in the earliest stages of Christian history.

We should not want the church to merely imitate the way it was in the past. We should explore the needs of the day, to see how we can and should adapt and develop the faith which has been handed down to us so that we can hand it down to the next generation. But, in doing this, we must be careful. We should not let ourselves be trapped by the ideologies and mores of our time and place. This is one of the reasons why studying patristics is helpful, for it will make sure our perspective is broad enough to do this. For by reading ideas of other times, especially that of the early church, we will be able to see beyond the prejudices of age. That is, just as we can and should be willing to criticize what we read, we should also let it criticize us. Moreover, reading them, we will find many of the same problems and questions which exist today existed in the earliest era of the church. We can learn from the way the church responded to them, adapting them as need be to fit the present situation, showing that the wisdom of the past can truly be of help to us today.

Thus, reading patristics can be a very productive element of our own theological exploration, but we must make sure it is not the only element of our studies. We need to make sure we understand the signs of the times. We need to know the theological and cultural discourse which is with us today and engage them. That is, we must do more than read patristics and repeat what we read, we must use prudence to adapt what we learned, to even improve what we have learned, to deal with questions and difficulties ancient writers could not have imagined. The church is meant to be a living church. The hopes of dreams of all can be and will be fulfilled in Christ, which means, Christ not only fulfilled the hopes and dreams of the past, but he fulfills those of the present as well.

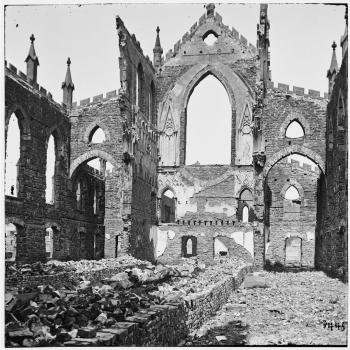

Dorothy Day understood this; she saw every age was riddled with its own problems, with Christians, including many of the leaders of the church, showing themselves to be far from what they should be. Nonetheless, she said there is a continuity which we can find connecting the church throughout the ages, a continuity which includes the work of the saints, those who helped reform the church of their age, as well as the sacraments, with the eucharist truly bringing us together and making us one:

In all history popes and bishops and father abbots seem to have been blind and power loving and greedy. I never expected leadership from them. It is the saints that keep appearing all thru history who keeps things going. What I do expect is the bread of life and down thru the ages there is that continuity.[3]

We, should strive to live out our faith, realizing that doing so requires more than just reading great theological works and contemplating what we can learn from them. We can and should look to patristic sources as one major source of our theological inspiration, but we must make sure we go beyond them as well. We need to learn from our contemporaries. We need to see and engage the needs of the day. Patristic resources might offer clues as to how we can do so, but we need to do more than just repeat the past, we need to adapt what we learned, modifying them with a critical eye so that their deficiencies will not hinder our engagement with the world we live in today. Everyone has their limitations; even patristic authors were imperfect. This means we will also be imperfect in what we do. Church leaders, as well, are imperfect, and will often make many disastrous mistakes. Nonetheless, the church will continue to fulfill its role despite all the defects of its members, including its best members. It is not just the summation of the people involved. It is more than that. It is the body of Christ enlivened by the Spirit of Christ. The church, despite the imperfections of its members, continues to be a sacrament of salvation in the world.

[1] Nikolaos Loudovikos, Church In the Making: An Apophatic Ecclesiology of Consubstantiality. Trans. Normal Russell (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2016), 12.

[2] Jean Daniélou, SJ, The Bible and the Liturgy (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1966), 8.

[3] Dorothy Day, “Letter to Gordon Zahn. October 29, 1968” in All The Way To Heaven: The Selected Letters of Dorothy Day. Ed. Robert Ellsberg (New York: Image Books, 2010), 452.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!