Monasticism demonstrates to us a radical way of life, one which embraces the “death to the self” which Jesus said all Christians need to engage, and makes it a central aspect of the way monks and nuns live their lives as disciples of Christ. To die to the self requires us to detach ourselves from all false perceptions of the self which arise from an egotistical, self-centered vision of reality. The more we let that false self perish, the more we will be able to know our true selves, and through such self-knowledge, we will become better equipped to deal with the burdens of life.

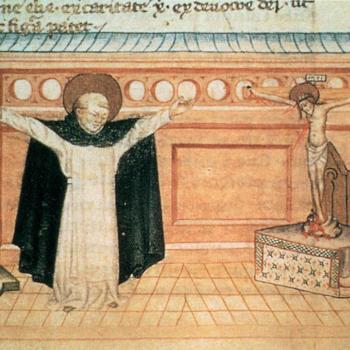

To help us know the practical implications involved with a true death to the self, some have used the example of a course, having us consider its reactions when it is mistreated. If someone attacks a corpse, it will not strike back. If someone insults it, it will not speak back. While there is value in in this reflection, we must be careful. We must not use it to say we should accept injustices in the world, telling people they should just ignore them instead of dealing with them, making sure they are overturned. That is why Timothy Jackson was right when he suggested we must engage spiritual wisdom with prudence, not absolutizing what we find in any particular text; what can be good for some, in some situations, can actually cause harm in others. Many invaluable disciplines can be abused and turned into tools for cruelty, the kind which no one should be expected to bear: “To enjoin an uncritical self-denial or passivity, utterly insensitive to context, would be a prescription for injustice, as many feminists have pointed out.” [1]

What is important, then, is to understand the point concerning the notion of “death to the self;” then we can better understand and find the right way to engage it and put behind us our false self. We must not be led to be indifferent to the injustices in the world, rather, the reverse. Indeed, those who have truly embraced “death to the self” will be more capable of addressing such injustices as they will have both overturned their own inordinate passions which would have led them to contribute to such injustice as well as they will no longer be led by those social pressures which rely upon people being only interested in their own private interests.

True Christian selflessness leads people to form loving, personal relationships with others instead of taking from and exploiting them. We must recognize the goodness we have in us, in our person, in order to see we have something worthwhile to share with others. Thus, while we are told that we must reject pride and vainglory, and all such passions which flow from our false self, to truly be humble, we will still recognize and accept that there is good in us, even as there is good in everyone else. Death to the self, death to the false egoistical self, will have us discern the person which exists underneath that false self, and free it from the prison in which it is found. In some ways, that person is dead to the world, but will become revived once the false self is destroyed. Our life, therefore, is not to be as an individual all by ourselves, but as a person forming loving relationships with others. Our salvation requires us to undermine all attempts to cut ourselves from others, because the more we try to do that, the more we tend to prop up our false self, which is something that Abba Poemen, had to learn:

Once Paësius, the brother of Abba Poemen, made friends with someone outside his cell. Now Abba Poemen did not want that. So he got up and fled to Abba Ammonas and said to him, ‘Paësius, my brother, holds converse with someone, so I have no peace.’ Abba Ammonas said to him, ‘Poemen, are you still alive? Go, sit down in your cell; engrave it on your heart that you have been in the tomb for a year already.’[2]

Paësius, at this point, knew something which Poemen did not, that is, his relationships with others, his friendships with them, was important, and should be factored in his spiritual development. Most monks, at least at some part of their spiritual journey, thought thought that, except for times of communal worship, they should cut themselves off from others and live a solitary form of existed. they were warned not to be too talkative because idle talk could easily distract them from their ascetic labors. To be sure, it can be a problem, but, likewise, ignoring the need for community can also be a problem. We are made to be engage others, and one way we are to do that is by talking with them. Thus, when Poemen went to St. Ammonas, one of St. Antony the Great’s disciples, complaining about Paësius, Ammonas quickly noted the problem lay not with Paësius but with Poemen himself. Poemen was pursuing an individualistic notion of the spiritual life, and in doing so promoted and helped keep alive the self-centered ego which monastic discipline was meant to root out. Poemen was “still alive” in the sense that his ego was still thriving; he had not mastered the death-to-self, and so, he had not learned how to engage proper personal relationships with others, relationships founded upon and guided by love. Ammonas pointed out that Poemen, like many of the desert fathers, might have lived in a literal tomb, but they had not learned the proper lesson they should have learned from their experience, for he had not learned the true meaning of death to the self.

We, too, should learn that same lesson. We too must fight against pride, vainglory, and all that comes from a selfish ego. We need to learn how to quiet that ego, to put it asunder, and as we do so, we will slowly find ourselves being liberated, and experiencing what can only be said to be the life which God intended us to have. We are called to know our true selves, not the false one which we put on as a mask. To know ourselves, we must have relationships with others, for it is only in and through the way we relate to others do we find who we are as a person.

Let us ask ourselves a few questions: Do we keep people distant? Do we deny the goodness in them? Do we try to prop ourselves up? Do we ignore injustices in the world? When we say yes to any of these, we must learn to change and deny our selfish ego and the false conception we have of ourselves due it. When we do so, we will see how that false self has caused not only ourselves much harm, but it has led us to needlessly harm others, as it is what has us not only ignore and deny the good found in others, but also, it will have us deny the love which we should show to them, a love which can be and is demonstrated in acts of charity but also in acts of justice (including the promotion of social justice).

[1] Timothy P. Jackson, “The gospels and Christian ethics” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Ethics. Ed. Robin Gill (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 47.

[2] Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Trans. Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1984), 164 [Saying 2 of Poemen].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.