“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God; all things were made through him, and without him was not anything made that was made. In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (Jn. 1:1-5 RSV).

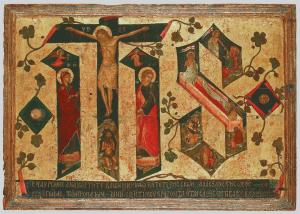

In the new beginning is the Word, the Word who had become man and then took on death itself so that so that all things that were made through him could be remade through him, cleansed from the taint of sin. In him was the life, the life and light of all humanity and the whole world. The light descended into the darkness of death, but death could not overcome it, for the light in its humility overcame the pomp of death. What had been brought about by sin, the spiritual death which destroys all things, was overthrown. The Word of God made flesh, in all love and humility, allowed himself to be taken in by the darkness, to be surrounded by it, but it could not and would not squash out the light. Thus, we read in the homilies of St. Peter Chrysologus:

Hell is caught, and set in its place. Death gets judged – death which, rushing against guilty men, runs into its Judge; death which after long domination over its slaves rose up against its Master; death which waxed fierce against men but encountered God. [1]

Death is judged: and it is found unacceptable. Death is judged, and the injustice of sin is overturned. Death is judged by the light of the world, and the justice of the grave, the justice of hell, is found wanting. It sought to take on the whole of creation, to take all things and hold them under the sway of its dominion, under the dominion of its nihilistic destruction. But it took too much. It took the God-man, the one who willingly let himself be taken by the powers of darkness, only to find that it had no power to snuff out his light, the light of creation itself. He was the light and life of the world, and though he willingly gave himself over to death, death was not his match: even in his humility, even in his silence, in the silence of the grave, as he let himself go powerless unto death, death found its power nullified: life is greater than death, and the author of life greater than the nihilism of sin.

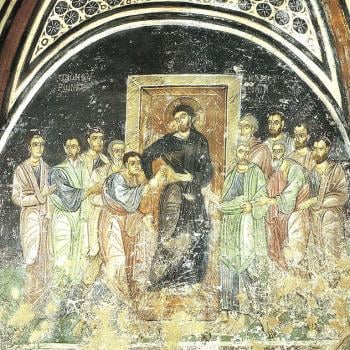

Christ’s death and descent into hell rearranged everything, even in hell itself. All who die now will come face to face with Christ. The afterlife is his. His light shines throughout it. This is what Sergius Bulgakov affirmed, when he discussed the eternal significance of Christ’s redemptive work:

To what extent is the power of the Redemption – Christ’s incarnation, passion, and resurrection – manifested in the afterlife? The answer is given not only by the dogma of Christ’s preaching in hell but also by numerous patristic texts concerning the victory over death and hell (which are crowned by the homily of St. John Chrysostom, which is the sermon read as the Easter vigil). Christ’s resurrection illuminated hell by its victory over death. This event should be conceived not as momentary or of short duration, but as permanent. In the afterlife, there is no place for anything that is not Christian, even among non-Christians, although, of course, each individual receives the revealed redemption differently, depending on his freedom.[2]

Christ is Risen!

Christ is Risen, and all of creation rejoices. Christ is risen: sin has met its end. Christ is risen, and the whole world is reconfigured by its Lord. Christ is risen, and the glory of God has been revealed. Christ is risen and the power of sin itself has been nullified. Death comes to an end in him, so that in him through him the eternal kingdom of God, a kingdom of light and life, is revealed.

Everything is new. Everything is different. Everything is to be transformed. The world, the universe, is Christ’s, and though it had been contaminated by sin, though it too felt the power of sin trying to nullify it and turn it towards nonbeing itself, the whole of creation finds itself restored in the resurrection of Christ. All things, all humanity, all of creation will find itself renewed in the eschaton. The change of seasons reflects this: Spring anticipates and presents to us the kind of glory which is to come, as Archard of St Victor understood:

To increase newness and joy, the world – which fell when humanity fell – will rise when humanity rises, and its very elements will be changed for the better. The form of this world will pass away, and so ‘we are awaiting new heavens and a new earth.’ The created world itself has been subjected against its will to vanity, but on account of him who subjected it in hope; it too will be freed from the slavery of corruption and into the freedom of the children of God. Now the world itself celebrates and echoes the Lord’s resurrection with its own partial resurrection and renewal. Think what the face of the earth was like a while ago, in the winter. Was it not shapeless, unattractive, and in a way empty and void? Now see what it has become, covered and graced with plants and trees, and embellished with flowers. [3]

The world itself shows forth the glory of God, and so the world itself shall partake of the eschatological glory of the resurrection. It already gives us a glimpse of the resurrection as we see the cycle of the seasons. We get a sense of death and rebirth in time itself, giving us a foreshadowing of its own eschatological reconfiguration as it finds its proper place in the kingdom of God.

Christ has brought us something new. But it is a newness which must be understood as not acting contrary to nature, but fulfilling it. Prior to the resurrection, nature existed in a fallen mode of being, which led it to act and being contrary to itself; in the glory of the resurrection, in the innovation given to it by grace, Christ does not change the nature of things, but its mode of existence, allowing it then to be elevated in a mode which can only be said to be supra-natural, as St. Maximus the Confessor taught:

Every innovation, generally speaking, takes place in relation to the mode of whatever is being innovated, not in relation to its principle nature, because when a principle is innovated it effectively results in the destruction of nature, since the nature in question no longer possesses inviolate the principle according to which it exists. When, however, the mode is innovated – so that the principle of nature is preserved inviolate – it manifests a wondrous power, for it displays nature being acted on and acting outside the limits of its own laws. [4]

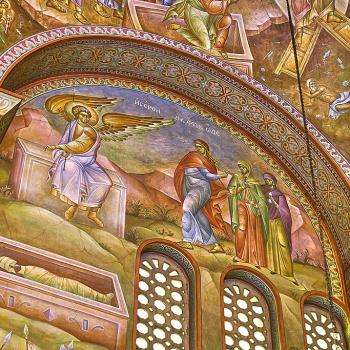

Christ is Risen! He showed himself to his disciples, he showed himself to his beloved, he showed himself to the world. In the days after the resurrection, he revealed the glory of God. St. Hildegard thus saw the continuation of the work of the resurrection manifested in and through his forty day between the resurrection and the ascension:

God remained visibly among us through his humanity, filling the entire earth with his miracles through those forty days after his resurrection. In that same humanity, which he assumed when he was conceived by the Holy Spirit from the Virgin Mary, he cleansed all the elements that had become sullied through the first human’s transgression. Accompanied by a throng of angels with the victorious banner of his power, he had redeemed from hell the once captive souls of the saints and those who were to be saved.[5]

In the time he had before his ascension, then, Jesus revealed the way he had cleansed all things, so that we could know that all things will be welcome in the kingdom of God. “By a wondrous arrangement, God confined all things under sin so that he might have mercy on all.” [6] All things were brought together as one, so that all things can receive a share of his glory. Nothing has been excluded: he who made all things remakes all things so that all things can share together the glory of God. Who can deny the light shining in the darkness, the light which shines upon all things, revealing their proper glory?

Christ is risen! Indeed, he is risen!

[1] St. Peter Chrysologus, “Sermon 74” in Saint Peter Chrysologus Selected Sermons and Saint Valerian Homilies. Trans. George E Ganns, SJ (New Yok: Fathers of the Church Inc., 1953), 125.

[2] Sergius Bulgakov, The Bride of the Lamb. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 371-2.

[3] Archard of Saint Victor, “For Easter,” in Works. Trans. Hugh Feiss, OSB (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2001), 159-60.

[4] St. Maximos the Confessor, On the Difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua. Volume II. Trans. Nicholas Constas (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 173 [Amb. 43].

[5] Saint Hildegard of Bingen, Solutions to Thirty-Eight Questions. Trans. Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Jenny C. Bledsoe and Stephen H. Behnke (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2014), 65.

[6] Archard of Saint Victor, “For Easter,” 161.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you have liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!