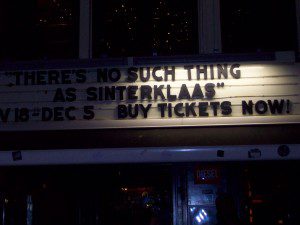

A few years ago, I came across David Sedaris’s essay 6 to 8 Black Men, a light-hearted look at how the Dutch celebrate the Christmas season holiday of Sinterklaas (Saint Nicholas) and his servant Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). Sinterklaas is similar to Santa Claus; he rewards good children with presents for their good behavior. The bad children, however, have to contend with Zwarte Piet, who beats them, kidnaps them and then sends them to Spain as punishment (really). Knowing that I’d be in the Netherlands during Sinterklaas I tried to mentally prepare myself to discuss this holiday, elements of which seem overtly racist to me, with my Dutch friends. However, nothing prepared me for the nausea I felt seeing real, white Dutch people walking in public streets in blackface, comically dressed as 19th century African pages.

As I continued to ask my friends about their thoughts concerning Zwarte Piet, I uncovered two interesting trends, that initially seemed disconnected. To begin with, there actually IS a socio-political movement to mitigate the racist elements of Sinterklaas. There have been countless public forums, documentaries and mass protests to address the racist elements of the holiday, mostly spearheaded by anti-racism activists of African backgrounds. A group of people even tried to remake the character of Zwarte Piet from a (former) black slave, into a magical rainbow-colored sprite. Mostly, these efforts have raised awareness of the issue, but have not succeeded in changing cultural attitudes toward this beloved Christmas tradition.

The second trend was astonishing, to my American ears. Most of the people I discussed Zwarte Piet with did not feel as though the character was very controversial. “It’s a children’s holiday; racism has nothing to do with Zwarte Piet” was the typical response I got from people I talked with, including those of white, Turkish and Moroccan backgrounds. At some point during these conversations, I wondered if I was letting my post-civil rights American sensibilities dictate how I viewed another culture’s holiday. After all, while The Netherlands does have a history of black slavery and colonization of black peoples, it does not have the same exact history as the United States and I could not view The Netherland s with American lenses.

s with American lenses.

But I soon realized a deeper reason for their seeming ambivalence: for many Dutch citizens, of all racial, ethnic and religious backgrounds, the racism in the children’s fantastical Sinterklaas holiday is overshadowed by the real struggles people of color – citizens of former slave colonies and descendents of North African guest workers alike. These Dutch citizens are designated as allochtoon, always considered as foreigners by their society, and face tremendous difficulties in obtaining equal opportunities to the education and jobs that would open a path toward upward mobilization. The Zwarte Piet debate is seen as a diversion from taking actions to promote the full economic and social integration of Dutch citizens of color.

One could argue that the Zwarte Piet debate is a result of the increasing diversity of The Netherlands; the earliest protests began in 1995 by black migrants and has continued ever since. As global migration grows and telecommunication technology continues to advance, all Dutch people are forced to look at their history with new lenses. This is not necessarily a bad thing. If the Zwarte Piet debate can help shed light onto the unequal opportunities for upward mobility that the majority of people of color in The Netherlands still face daily, Dutch society will be better for it and Zwarte Piet can stay as he is: a relic of 19th century minstrelsy.