This is Day 29 of Hindtrospectives’ #MyMosqueMyStory series for Ramadan 2015

By Shereen Yousuf

Bismillah

Though there is no shortage of beautiful people and devoted followers in my community, I have to admit that my mosque fits the archetype of negative mosque experiences. This includes everything from women being crammed into the basement while men have the “main hall” upstairs, to what appears to be the timeless perils involving domestic violence and the stigma attached to divorce in South Asian communities. My understanding of the injustices that we see emerging within our religious institutions is complicated given the intersectional nature of oppression itself. For example, we cannot understand patriarchy within our communities without recognizing the ways that anti-Black and anti-immigrant racism has played in molding it. That being said, I often wonder why it is that Muslim communities rarely include sectarianism as part of the intersectional oppressions we must combat within our own communities, specifically Shiaphobia in U.S. Muslim communities.

It’s worth explaining that there are an abundance of similarities between the Sunni and Shia traditions, such as our shared conviction in Tawhid or the “oneness of God,” our love for the Prophet (pbuh), and the Qur’an as a source of guidance. However, one of the major differences lies in the emphasis each places on the Prophet’s family, or the “Ahlul-Bayt” which translates to “people of the house.” Shias believe that Allah designated authority to certain members of the Ahlul-Bayt following the death of the Prophet, who in essence, inherit the Sunna (as I heard one scholar say) and provide continued guidance on social and spiritual matters.

Years of intrafaith discussions with not-so-veiled questions have taught me that Sunni Muslims are suspicious of the degree to which to which we love the Ahlul-Bayt, suggesting that we have made them “God-like,” which is clearly un-Islamic. In my humble opinion, this discomfort stems from Sunni-centric approach to how certain figures are revered in relation to Tawhid . As a Shia, I feel that the narrations, supplications, and general literature attached to the Ahlul-Bayt are crucial in drawing me closer to Allah, especially given the degree to which many of them were marginalized themselves and expressed devotion to Allah from that positionality.

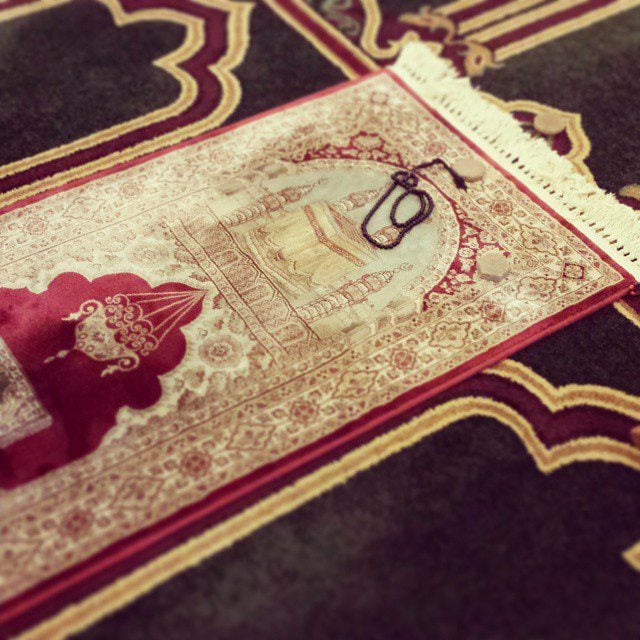

This is important to recognize because here in the U.S., Sunni Muslims occupy the “normative” position and homogenize what it means to be Muslim on the basis of their sect. If you question this, consider how it might be odd for a Muslim organization with no sect affiliation to provide turbas, or pieces of clay that many Shia Muslims use while prostrating, in their prayer rooms. The fact that this act of inclusion may seem abnormal indicates that there is, in fact, a norm to begin with. This piece by Abbas Rattani relays how this transcends to interpretations of Islamic history as well. Though I recognize anti-Sunnism certainly exists in Shia communities, I focus on Shiaphobia because it is Shia Muslims that are marginalized and Sunni communities that have privilege here in the U.S.

When I’m in my Shia mosque, I can express my love for the Ahlul-Bayt (pbut) without that love being perceived as excessive, un-Islamic, or self-seeking. I’m not met with suspicion if I’m really a Muslim and I don’t have to account for a different interpretation of Islamic history or exegesis of the Qur’an. Also, in light of growing sectarianism globally, I don’t fear being asked to represent all Shias for anti-Sunnism taking place in other counties, while wondering why Sunnis aren’t simultaneously pressured to hold themselves accountable for anti-Shi’ism taking place globally in places as wide-reaching as Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Egypt, Malaysia, and even here in the U.S.

However, my mosque experience is complex because I wonder how I can join important mainstream Muslim causes to end racism, patriarchy, classism, ableism and more when at the same time, I encounter experiences that erase the entire existence of my community with remarks like, “we are not Sunni or Shia, we’re all Muslim,” or make me feel shameful about expressing my profound love for the Ahlul-Bayt, which is so attached to my beliefs in Islam, with raised eyebrows questioning my Muslim-ness.

Ramadan forces me to confront this tension because I’m reminded of how, on one hand, I have so many concerns that I share with Muslims outside of the Shia community, yet, on the other hand, I have a sense of belonging that I can only attain in a Shia space. This is all the more frustrating when Sunni Muslims don’t recognize the loss that stems from alienating Shia Muslims from the entire Islamic tradition, namely by the lack of awareness about resources attached to Shia tradition. To be blunt, the foundation of anti-Shi’ism for me lies not in the acts of violence that occurs against Shia Muslims, but in the inability to perceive Shias as Muslims in the first place, which rationalizes these aggressions.

I would like to end this piece with a call to Sunni Muslims who are working tirelessly and with the sincerest of intentions to undo the oppressive social structures that plague our mosques, to include Shiaphobia (and any “phobias” attached to other non-Sunni sects, for that matter) as an integral dimension to this intersectional fight. Because injustices crosses sectarian lines, combatting Shiaphobia within your own communities will strengthen the ability for us, as Muslims, to truly heal our communities together from the injustices we collectively face. This can only happen if Shia Muslims do not feel further marginalized in these movements.