Indian art has the capacity ot make the impossible seem possible. When Valmiki described the heroism of the monkey chief, Hanuman, he made him carry the hill Gandha- madana and jump over the ocean’ But we are not surprised at it. The way in which Valmiki was preparing our mind made it possible for him to represent the ten-faced and twenty-handed demon of tyranny, Ravana, and the feats of the super-heroic Hanuman, and did not in the least interfere with our enjoyment of the Ramayana by suggestions of the impossibility of the description.

Just as when we read a work of Yoga we are prepared to believe the possibility of the Yogins living in a state of samadhi for months together under the ground without air and without food, so the poet also has the privilege of creating his own characters in his own way without being fettered in the least by the laws of nature. Mammata, the great rhetorical thinker, observed this special feature of artistic creation and, in the very beginning of his work, described the creation of the poet as being unfettered by the laws with which nature had fettered herself (prakrti-krita-niyama-rahitam). This tendency and peculiarity of poetical creation is also found in the work of an artist.

Thus in the plastic representation of Mayadeyi, the mother of the Buddha at the time when the Buddha was being born, we find a big elephant entering into her womb. Though in the representation the side of the elephant was equal to the size of Mayadevi herself, the artist was not in the least disturbed by the fact that an elephant of the size of Mayadevi could not very well enter into her womb, and that it was physically impossible that a body occupying a larger area could be contained within a space which was much smaller. We need not think that the impossibility did not strike the artist, for it was too obvious. But the artist simply ignored the claims of the laws of nature to limit the scope of the artistic activity.

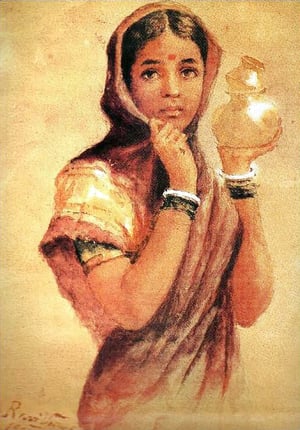

This is what makes Indian art unique. Again, when a group of composite figures were drawn in association with the plants and creepers of nature, the separate figures indicated nothing in themselves. The artist was careful that he might not represent those figures in such a manner that by their appearance they might disturb the total effect that was intended to be produced. The aim of the artist was fixed not on the parts, but on the whole. The parts, therefore, were subordinated to the interest of the total content.

In the total content, again, there may be one idea, one emotion that was the soul of the total representation. This idea may be the idea of peace in the face of the Buddha or the idea of the harmony and friendship between the human spirit and the spirit of the world outside, that manifested itself through animals, birds, trees and creepers.