Today’s post is a sermon I delivered this past Sunday, on a topic that will be familiar to regular Holy Rover readers: Holy Silence.

One of the pleasures of being married to my husband has been the many stories I’ve heard through the years about philosophers and their peculiar habits. One of my favorites is about a friend of Bob’s who several years ago gave a lecture in a philosophy class and then was asked a follow-up question by a student. In response the professor said, “You know, that’s really a good question. Let me think about it.” And then he sat down and thought about it. And then he thought about it some more. He furrowed his brow, he got up and paced across the floor, he stood looking out the window with a faraway look in his eyes. The minutes ticked by slowly as the students watched him in growing bemusement. Finally he gave his answer, clear and well-reasoned. And after class the students spread the story as proof of just how strange philosophers can be.

What flummoxed the students, of course, was the extended silence. Most of us are uncomfortable with silence, especially in a public setting such as that. But even when talking privately to a friend, we typically rush in to fill any pause with words. So the example of the philosopher in class, of someone being comfortable with an extended silence, conveyed a message that probably went unlearned by most of his students.

The story is a small example of a much larger truth: silence is powerful. In its deepest form it is not the absence of something, but rather a mystery holding unfathomed potential. There’s perhaps no more beautiful example of this than the story we heard this morning from 1 Kings. In it, Elijah encounters God in a most unexpected way. As I read part of this story again, keep in mind that in the ancient world, divine beings were almost always synonymous with the forces of nature. There was the god of thunder, the god of the sea, and so on. But the Hebrew God was different, as Elijah learned as he stood in the mouth of the cave:

Now there was a great wind, so strong that it was splitting mountains and breaking rocks in pieces before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind; and after the wind an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake; and after the earthquake a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire; and after the fire a sound of sheer silence. When Elijah heard it, he wrapped his face in his mantle and went out and stood at the entrance of the cave.

The sound of sheer silence. That’s the line that has intrigued theologians and mystics throughout millennia, hinting at a paradox that lies at the heart of the spiritual path. We often think of religion as being all about words—sacred texts, liturgies, prayers, and doctrine. But these are actually the vessels that hold an even greater treasure within, a truth that is beyond all words.

There are many types of silence, of course. There’s the blessed quiet after a colicky baby stops crying, or the sorrowful silence in a house after a loved one has died. Think of the hushed silence just before dawn or the bruised silence that lingers after a fight with a friend. We might think of these as lesser silences, but they nevertheless point to the truth that silence has power, texture and meaning.

Last month Bob and I had the pleasure of attending an event in Louisville, Kentucky, called the Festival of Faiths. This year’s theme was “Sacred Silence: Pathway to Compassion.” For five days, religious leaders and theologians from a wide variety of faiths got together to talk about the transformative effects of silence in their traditions. Now, I realize there’s something ironic about all these people using lots of words to talk about silence—just as there’s also something funny about giving a sermon about silence. But to paraphrase a Buddhist saying, while we shouldn’t confuse the finger pointing at the moon for the moon itself, sometimes we need a guide to point us in the right direction.

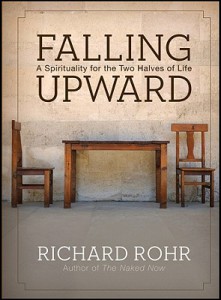

It was fascinating to hear these wise people wrestle with the many implications of holy silence. My favorite presentation was by Richard Rohr, a Franciscan priest and author of many books on contemplation and spiritual development. He reminded us that silence is a fundamental discipline in all the world’s religions—perhaps the most fundamental discipline. This silence is not just an absence of words or being alone; it is an alternative consciousness. This holy silence is most often the product of many years of prayer and meditation, disciplines that help us open ourselves to the divine presence.

Rohr puts it this way: “The ego gets what it wants with words. It prefers immediate answers, full clarity, absolute certitude, and moral perfection. But the soul finds what it needs in silence. It is silence that allows us to be at rest, expectant, and open. Silence is a living presence that creates a resonance within us to the holy.”

We may think this type of silence is only for the professionally religious, for Buddhist monks and cloistered nuns. But all of us know intuitively of the power of silence. Think of those times when it has blossomed within you—perhaps after hearing a piece of beautiful music, seeing a spectacular sunset, sitting at the bedside of someone who is dying, or holding a newborn baby in your arms. The deepest, most heartfelt honoring we can give to an experience is silence.

Now both as a writer and as a member of the clergy, I realize that this approach violates union rules. After all, these professions are based upon the importance of well-chosen words, whether they’re crafted by an individual or handed down as doctrine or sacred text. But the older I get, the more I see how limited words are and the less I trust them to convey what is truly important. I think St. John of the Cross is right in saying that “Silence is God’s first language.” Everything else is a translation.

In Richard Rohr’s presentation at the Festival of Faiths, he spoke of silence as a form of voluntary poverty. Not poverty in a deprived sense, but poverty as a discipline and teacher, as St. Francis modeled so beautifully. This is the silence that surrounds everything. Rohr described it as the space between letters, words, and paragraphs that makes them decipherable and meaningful. It is the interweaving between notes that makes music possible. It is the divine silence before, after, and between all events, the fount from which all grace flows.

If you’re like me, your relationship with silence is likely problematic. I’m a veteran of many failed attempts at Centering Prayer and other forms of meditation. And in my day-to-day life, too often I’ve rushed to respond in frustration or anger rather than letting silence temper my opinions. Email compounds this problem, of course, as anyone knows who has ever hit “send” and then regretted it a second later. So this idea of intertwining our lives with silence intrigues me. Few of us can be Trappist monks, but all of us can practice letting holy silence enter into our lives in smaller ways.

There’s a wonderful book by George Prochnik called In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise. The author has long been fascinated by silence, so much so that he spent years learning about it. During his research he attended Quaker church services, visited Gallaudet University for the deaf and interviewed scientists working in acoustical research. One of the places he visited was New Melleray Abbey, the Trappist monastery near Dubuque. A monk there talked about the lessons he has learned from his long experience with silence. “Without it,” he said, “people have no ability to understand one another.”

The monk went on to say that he often helps facilitate meetings for various groups that are visiting the abbey, and that he has learned that difficult decisions should not be made by discussion alone. Simply talking about hard decisions means that (in his memorable phrase) “the noise makes the decision.” Think about that phrase for a moment: the noise makes the decision. We’ve all had that experience, haven’t we? Too often it’s the loudest voice that highjacks a discussion.

Instead, when a group is facing controversy and dissent, the monk begins by sending everyone off to meditate on their own place in the conflict. After an extended period of time, the group will re-convene. Many times the monk finds that the silence has changed people’s minds. They will tell him: ‘Father, I was out walking, and I found myself thinking about all the other people in the group and how I would feel if I were them. I’m not so sure I’m right about this issue after all.”

Prochnik gives another example of the power of silence on a much larger scale. He tells of being in Israel one time during its annual commemoration of the Holocaust, a day when there is a two-minute period when all activity pauses as people remember the millions who died. He describes feeling completely overwhelmed as he watched the traffic lights change color with no car responding to their signals, of seeing people freeze in place on the sidewalk and bow their heads. He writes this about the experience: “Silence seemed to create a hole in the present into which the unspeakable past poured in a flood, swallowing our individual lives. At the end of it, the trivia surrounding those two minutes sounded painfully loud. I wanted somehow to live up to that moment of suspension.”

There are many tools that can help us learn about silence. In the Christian tradition, we have Centering Prayer, while the Buddhists can teach us about meditation and mindfulness. But I think all of us can incorporate more silence into our lives, even in small ways. Here’s a personal example of something I realized in writing this sermon. Each Sunday before I read the Gospel, I make the sign of the cross on my forehead, mouth and heart. I’ve come to appreciate how those few seconds of silence, as short as they are, help me to stop the internal dialogue of self-consciousness. They help me to remember what is important.

Let me end with a testimony to the power of silence from the scientific world. It comes from University of Virginia astronomy professor Mark Whittle, who has studied the sound of the Big Bang that began the Universe. Whittle believes that in the first instant, the sound would not, in fact, have been a big bang at all, because the initial explosion consisted of a perfectly balanced, radial release of energy. The Universe was born in silence.

And in this research finding, science is in perfect harmony with the mystics of many faiths, who have also sensed the creative force of Holy Silence. It was there at the beginning of creation, it was there at the mouth of the cave with Elijah, and it is with us whenever we try to enter into it, as halting and fumbling as our attempts often are. I invite you to join me now in entering into this holy silence for just a few minutes.